MONDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2023. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Featured Image: Early 1900s photograph of Woock Vineyard—consisting of furrow-irrigated Flame Tokay, Zinfandel, and Alicante Bouschet—owned and farmed by one of Lodi’s leading German-Russian families. Courtesy photo.

The first German families

In any conversation about the most important farming families in the Lodi winegrowing region, one particular ethnic group stands out above all else: Lodi’s German community.

Germans, of course, were one of the many groups from around the world descending upon California after gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848. “Three German miners,” according to pbs.org’s American Experience, “made an immense find in the extreme northern section of the gold fields… Rich Bar [a Plumas County gold mine, marked as California Historical Landmark No. 337] would produce some $23 million of gold ($561 million in 2005 dollars).”

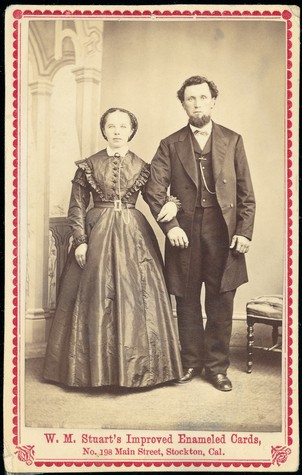

The July 25, 1870 wedding portrait of Joseph and Anna Spenker. Jessie’s Grove.

Joseph Spenker—the great-grandfather of Wanda Woock, who owns and operates Jessie’s Grove with her son Greg Burns on the west side of Lodi’s Mokelumne River appellation—was a German immigrant from Dargun in the north of Germany. Spenker was still grappling with the English language while attending school in Stephenson County, Illinois when he first caught wind of the Gold Rush. Writes Woock in her book Jessie’s Grove: “Everyone was talking about California and the gold just waiting to be picked up, riches beyond imagination could be found!”

In 1859 a 23-year-old Spenker hitched onto a wagon train to California, which Woock says “took 154 unforgettable days… At times they felt like they were barely moving, and at two miles per hour, that would be close to the truth.”

The Spenker home in 1871; all that remains today, on the Jessie’s Grove estate, is the original palm tree. Jessie’s Grove.

When he finally arrived, Spenker traded his horse, his sole possession in the world, for a claim in Murphy’s Camp, which yielded absolutely nothing. Virtually penniless, he eventually made his way down to Stockton and began earning enough money working on a farm and as a dry goods entrepreneur to purchase, in 1869, a square mile property near the settlement of Woodbridge, just west of Lodi, still known to this day as Spenker Ranch, as well as Jessie’s Grove (the family’s winery brand, named after Spenker’s daughter Jessie).

Also in 1869, Joseph Spenker’s wife-to-be Anna Schliemann arrived via the Transcontinental Railroad in Linden, California from Hamburg, Germany. Schliemann was employed by another family as an indentured servant. Soon after, she met Spenker at a wedding reception. Sparks flew, and the following day Spenker came by on a two-horse wagon while she was doing the laundry outdoors. He announced that he was there to take her to Stockton to get married, and that was that.

Jessie’s Grove, the 32-acre stand of valley oaks that gives the Spenker-owned winery its name, is still preserved by the family to remind the world how the Lodi region originally looked before the land was cleared for farming.

Here is how Woock describes Spenker’s first impressions, according to family lore, of his 160-acre property near Lodi, which he originally named Adobe Ranch:

The land had hundreds of oak trees, and although it would be work to clear some of them for planting, with the trees growing so abundantly, he knew the quality of the soil would be excellent. He later told how he had walked into the main grove and knew instantly it was his intended destination in California. He said the majestic trees towered over his head, reaching for the sky with strong limbs that were the color of damp earth. It was early spring, and the limbs ended in complex patterns of delicate branches—black lace against the clear blue sky. Here and there, a hint of pale green was showing, so slight it almost wasn’t visible. As he stood in the grove, a hawk soared away from a nest in one of the trees. Soon it would be returning home, and Joseph knew he had found his home.

The original Lange family Lodi homestead in the 1800s. LangeTwins Family Winery & Vineyards.

Around the same time, during the 1870s, other German families such as Johann and Maria Lange—whose descendants now operate LangeTwins Family Winery & Vineyards, one of the largest and most influential of Lodi’s winegrowing families today—were also settling in the region along the banks of the Mokelumne River.

The Langes’ reverence for this farmland, while not enshrined in a book like that of the Jessie’s Grove, is evidenced by their multi-award winning sustainable innovations—in Lodi, formulated as the third-party certified LODI RULES for Sustainable Winegrowing—particularly their 100% commitment to the restoration of native flora and wildlife along the vineyard and riparian corridors. They do not farm their thousands of acres in this fashion because they have to. They do it on basic principles, much of it ingrained in their fidelity to heritage.

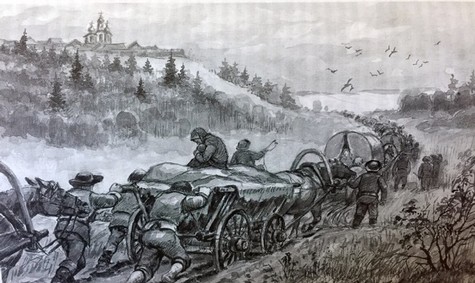

Migration of German colonists to Volga River Valley. Illustration (“Das Manifest der Zarin”) by Victor Aul, volgagermans.org.

The impact of German-Russians

The most important group of German descendants in the Lodi region, as well as throughout the farming communities of San Joaquin Valley, were what is called German-Russians—also called Russian Germans, as well as Volga Germans (the latter in reference to a large chunk of this group who migrated to regions in the vicinity of Russia‘s Volga River Valley).

The first wave of German Russians arriving in Lodi began in 1897—a period of time when the region’s predominant crops had already transitioned from wheat and watermelons to table and wine grapes.

1745 portrait of Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich (future Peter III) and his wife Grand Duchess Catherine Alexeevna (the future Catherine II) by George Christoph Grooth.

The German-Russian history in California’s Central Valley is one of many great American stories. It actually started across the ocean in 1762, with a manifesto issued by Russian Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796). Born in Germany as Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, Catherine married the future tsar of Russia, Peter III, at the age of 16. She assumed the Imperial Crown of Russia in 1762, after overthrowing her husband.

The story takes another turn one hundred years later in 1862, when the United States passed the Homestead Act which made it possible for practically anyone to apply, and to receive free of charge, public land—most of these homestead properties located west of the Mississippi River. This would be a clarion call for many Volga River Valley German-Russians who were originally there at Catherine the Great’s invitation.

The Lodi Hotel around 1900—when the city was just emerging from its rowdy, misbegotten “Wild West” era—which stood at the southwest corner of W. Pine and Sacramento Streets until torn down in 1912, becoming the second site of the Bank of Lodi (the building now housing Graffigna Fruit Co.)

A Lodi native named Richard Hieb—whose forebear Wilhelm Hieb has been called the community’s “Columbus” for his key role in leading to the migration of significant numbers of German-Russians into the Lodi area—recently commented in Lodi News-Sentinel:

Prior to the arrival of the German-Russians, Lodi was a wild and rowdy town consisting of 14 saloons and only four churches. Within 10 years of their migration, Lodi had 123 churches and four saloons. The conservative influence of these German-Russians transformed Lodi into a respectable city. By the mid-1930s, Lodi’s population consisted of 50 percent of German-Russian extraction.

In the most recent issue of The San Joaquin County Historical Society & Museum News & Notes (October 2023), there is a reprint of a 1988 The San Joaquin Historian article originally penned by Sandra L. Cole that dives deep into the history of German-Russians. Cole starts by reflecting on this group’s impact on the region’s economy and culture:

Even to the casual observer, there is something unique about the modest agricultural community of Lodi. Located in the flood plain of the Mokelumne River in the fertile San Joaquin Valley, and encircled by a sea of vineyards, Lodi has developed a rare environment compared to other California towns that started as farming settlements.

The highest standards of civic pride among its residents are reflected in the tree-lined avenues and well-tended homes. The abundance of churches gracing the street corners displays a zealous devotion to the freedom of religious worship. The large city parks within well-planned residential sections show an appreciation for the close-knit relationship between man and nature that is the basis of farming life.

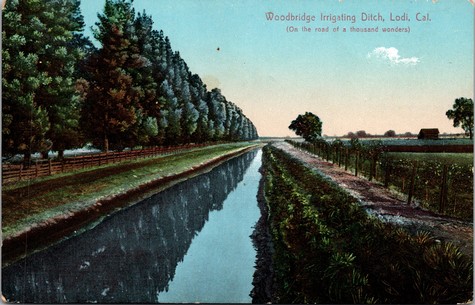

Postcard of a Woodbridge Irrigation Company canal on the west side of Lodi’s Mokelumne River, depicting this lush winegrowing region at the turn of the last century.

The comparison between Lodi and her sister city Stockton, just ten miles to the south, is striking. Stockton has encouraged industrial growth and continues to encroach upon its agricultural land with housing developments. Lodi has fought against such developments and industrial expansion, thriving to maintain its character and preserve its environment, and to protect the industry which has given it world renown, the wine industry.

All this reflects the characteristics of an ethnic group that settled in the Lodi area at the beginning of the present century. The history of their migrations and cultural traditions bears testimony to the degree that Lodi has been influenced by its German-Russian heritage.

Children of German-Russians hoeing sugar beets in the Volga River Valley. Library of Congress.

German migration to Russia

According to the State Historical Society of North Dakota: “When Catherine the Great became Empress of Russia in 1762, she issued a manifesto to her native Germany offering free land, financial help, and freedom from military service for Germans who would come to Russia to develop the land. Hundreds of thousands of Germans answered the call, to leave the crop failures in Germany, as well as lack of living space and high taxes.”

Cover of “Das Manifest der Zarin” depicting German villagers reading Manifesto issued by Catherine II.

Anne Bennett, writing in ndhorizons.com, quotes Rachel Schmidt of Germans from Russian Heritage Society as saying, about conditions in 17th and 18th century Germany: “The economic conditions were such that its people were plagued by hunger, diseases, and abject poverty… By the providence of God, many Germans believed Russia was opening her vast empire to struggling peoples at just the right time.” According to the American Historical Society of Germans From Russia, more than 100,000 Germans settled in Russia between 1763 and 1871, establishing their own German-speaking colonies.

German-Russian colonists resting at a stop on their way to Russia’s Kamianets-Podilskyi in the 1800s.

Tsarina Catherine the Great’s invitation to Germans to settle in the Volga region (much of this area now falling in present-day Ukraine) was intended to help her adopted country colonize vast, empty stretches of Russia. The invitation came with promises, according to Schmidt, which “included freedom of religion, certain tax exemptions, some free land and cash grants, exemption from military service, the right to use their own language and to build their own villages, schools, and churches.” An offer many of them could not refuse.

Russia’s 1861 Emancipation Act, freeing serfs from forced servitude, signaled a turning point. Under subsequent government decrees, even the country’s German-Russian became required to fulfill military service—an affront to these communities, many of whom still preserved their particular dialect of the German language, devout religious beliefs (mostly Protestant, but also Catholic and Mennonite), customs and culture dating back to the previous century.

Illustration of Volga Germans by Jakob Weber in “Talent from the Volga” (book by V.G. Khoroshilova). volgagermans.org.

In 1871 the Imperial Russian government repealed the manifestos of Catherine the Great and Alexander I (1777-1825), divesting German colonists of all their privileges or exemptions. Even after over 100 years, most of these German Russians were not completely “Russianized,” many of them having no intention of ever doing so.

Those who were willing to stay to become assimilated would end up suffering immensely—through the 1920-1923 Russian Famine (when an estimated 150,000 Volga Germans died of starvation), 1928-1940 Stalinism (period of brutal religious persecution, when German-Russian properties were seized and former owners were forced onto collective farms), and WW II (during the conflict with Germany Russians of German ancestry were banished to Siberia).

German-Russian settlers in North Dakota at the end of the 1800s. culturaldiversityresources.org

The call of the Great Plains

In retrospect, the more fortunate ones were those who took up the offer entailed in the Homestead Act signed in 1862 by Abraham Lincoln, and made the long, arduous journey across the Atlantic Ocean to settle in America, mostly on the Great Plains. Writes Cole:

Huge numbers of immigrants flooded in, especially from Northern Europe—including German-Russians. Because the latter were conspicuous and somewhat alienated by language (archaic German) and attire (Russian), they settled in their own enclaves, especially in the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Kansas.

The early years in the prairie were hard. Many men came alone to work and save and send for their families later. Industrious and frugal, and handicapped by language, they often accepted the most menial labor. Men worked for the railroads or in any other type of typically backbreaking work… Those who went out to homesteading immediately, or later, found it to be a primitive struggle that taxed their energy, intelligence, stamina, and other qualities to the utmost…

Remains of German-Russian stone barn in the prairies of Western North Dakota. Susan Quinnell, blog.statemuseum.nd.gov.

The Dakota prairie resembled their Russian homeland, in many ways, and they applied familiar wheat—raising practices with excellent results. The maxim for daily was, “Work’s fun.” Any child, boy or girl, was sent to work in the fields as soon as the child was strong enough to wield a hoe…

The hardscrabble rural life out on the Great Plains in the late 1800s was not as conducive to the Americanization of German Americans as it would eventually be in the farmlands of California’s Central Valley in the early 1900s. Adds the State Historical Society of North Dakota:

The German-Russians were noted for their strong work ethic. This means they valued work, and they worked hard. Many of the German-Russians felt that working to make a living was more important than getting an education, and most thought that high school and college were unnecessary.

German-Russian laborers in North Dakota. State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Even though schooling may not have been important to some of the German-Russians, they expected their children to behave when they did go to school. Children were told that if they were punished in school, they would get punished again when they got home.

When the Germans and German-Russians came into contact with each other in North Dakota, they usually did not have much to do with each other. The Germans from Russia had kept their customs, traditions, and language the same as those of their ancestors who had moved to Russia a century before. Germany, on the other hand, had become more modern, and their culture and language had changed somewhat. The Germans sometimes had a hard time understanding the speech of the German-Russians, who spoke what the Germans called “low German.”

German-Russians were proud of their traditions and did not want to be absorbed into American culture. They kept their tight-knit communities and continued to speak the German language for many years.

In a publicity photo for the 1935 Grape Festival, Yanez Jackson poses with Lodi’s signature grape, Flame Tokay, in a traditional German peasant dress, while Cliff Gatzert wears the attire of a Russian Cossack. Lodi Historical Society.

California dreamers

While accustomed to extreme hardship, many German-Russians were savvy enough to know they could do better. As Cole continues in her narrative on their continuing migrations:

Although their new homes were flourishing, there were some undesirable circumstances that led the more restless German-Americans to wonder about an even better “valley beyond.” Dakota winters were very harsh, accompanied too often by epidemics of diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, and smallpox. Children aged three to five were especially hard hit… their losses were heartbreaking. They suffered some wheat failures also, encouraging thoughts of a soil and climate that could produce a variety of crops.

Early 1900s photograph of August and Magdalena Hoff, the South Dakota-born parents of Paul Hoff who migrated to Lodi in the early 1930s. The Hoffs in this photo remained in South Dakota but are the great-grandparents of Lori Felten, who owns Lodi’s Klinker Brick Winery with Steve Felten. Besides Hoffs and Herrs, the Feltens trace their lineage to other well-known Lodi families such as the Mettlers and Woocks, most of whom are Germans who immigrated from Russia by way of the Dakotas.

Thus it was that a group of “scouts” arrived in Stockton, California, in the spring of 1896: Wilhelm Hieb, Gottlieb Hieb, Ludwig Derheim, and Jacob Mettler. They represented several well-to-do, established families from Menno, South Dakota, attracted by reports of available prime agricultural land in the San Joaquin Valley. By prearrangement, they were met at the railroad station by Otto Grunsky, a German-speaking real estate agent with ties to a bank holding foreclosed properties in the Lodi area.

Their reports were justified by what they found: excellent land, ideal climatic conditions, and reasonable costs, to provide a basis for diversified farming.

Wilhelm Hieb and Ludwig Derheim bought parcels immediately and the former came to be known as “Columbus.” Hieb because he was first to bring his family and settle at Lodi, in 1897. Derheim unfortunately died before returning to South Dakota, but as good reports spread among other German-Russian families in the Midwest, a significant movement was started.

The Lodi train depot in 1900, right around the time the first wave of German-Russians were arriving in Lodi, mostly via railroad. California Historical Society Collection

How Lodi’s “Columbus” made landing

The Dakota Datebook Archive (news.prairiepublic.org) gives a more detailed account of “Columbus” Hieb’s selfless generosity:

Hieb (heeb) was born in Russia in 1852 and came here with his young wife, Catharina, on the S.S. Hermann in 1874. They settled in Hutchinson County, Dakota Territory, near what is now Menno, South Dakota. Catharina died during their tenth year together.

After two decades on the prairie, Wilhelm missed the more temperate climate of south Russia, so he decided to find a place more similar to where he grew up. In 1895, he and two friends, Gottlieb Hieb (no relation) and Jacob Mettler headed for California and toured the state by train.

Wilhelm liked Los Angeles and its orange groves, but he wanted to grow grapes. They headed north and finally found the perfect place: Lodi. Hieb went back to Dakota, sold his land, and became the first German-Russian to move to Lodi.

A new (2022) headstone for “Lodi’s Pioneer for Germans from Russia” was installed by the Hieb family at Lodi Memorial Cemetery. Tammy Lyn.

With him were his second wife, Charlotta, and their eight children. In 1975, Hieb’s youngest child, Pauline Walters, told the story to the Lodi News-Sentinel. Her father bought 30 acres a mile south of Lodi and planted some of it into Zinfandel and Mission grapes. The rest he put into pasture to raise cows to keep them afloat until the grapes were mature enough to produce.

It wasn’t until a few years later that others began to join them. Polly said when other Dakotans began arriving, they’d always stay with the Hiebs. The town did have a hotel and a restaurant, she says, “but this wasn’t for the thrifty Dakotans. People came and went from our house, and this went on for years. Sometimes families would stay with us for two or three weeks until they could find a place.”

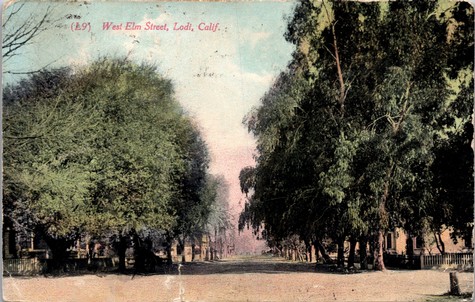

Early 1900s photographic postcard showing Lodi’s W. Elm St., near the center of the city.

It was about this time that Wilhelm became known as “Columbus,” as he enticed more and more of his former neighbors to migrate to Lodi. Even his mail came addressed to Columbus Hieb. He would meet Dakotans at the train depot and drive the men around until they found what they needed. Land was inexpensive—about $25-35 an acre—and the sandy soil was ideal.

Some people farmed, others worked in wineries or canneries. Nearly everyone prospered, and the migration increased. Back in Dakota, it became a sort of joke among German Russians—to ensure their children’s survival they taught them three words in English: Papa, Mama, and Lodi.

Polly remembered a day in the early 1900s when an entire train car of Dakotans arrived. This time there were so many, that their home wasn’t large enough to accommodate everybody. Her brother was sent on horseback to tell earlier migrants to come and get some of them. Meanwhile, she helped her mother prepare food for everybody. “It didn’t matter how many came,” she said, “we always had food. We learned how to manage on the spur of the moment.”

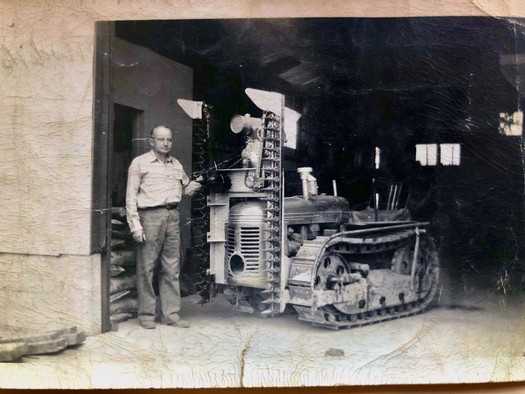

Eric Woock (1897-1972)—grandfather of Klinker Brick Winery owner/grower Steve Felten—was one of Lodi’s more prominent German-Russians; a gold miner, a masterly farmer (wheat and wine grapes) as well as inventor (in this 1946 photo he is standing with one of his inventions, a mechanical vine trimmer running on continuous tracks). Courtesy photo.

Early 1900s expansion of Lodi’s German-Russian community

Cole continues her story of the growing number of German-Russian families on the east side of Lodi:

In addition to families already named, other arrivals between 1897 and 1915 included the Handels, Schmiedts, Schnaidts, Preszlers, Bechtolds, Benders, Nies, Baumbachs, Reimches, Kirschenmanns, Finks and Lachenmalers. Their arrival impressed local residents, adding to local pride in the area as a fine place to live.

The new settlers moved in quite a different style from those who had arrived—not long before, really directly from Russia… These people had means, could buy substantial acreages immediately, and move directly into pre-existing buildings. They enjoyed a comfortable train ride, families usually traveling all together, from the Dakotas to Lodi.

1920s photograph of the Red & White Store in Victor, just east of Lodi; proprietor John Nies (among the first wave of German-Russian immigrants arriving in the late 1890s) standing in front. Lodi Historical Society.

They continued as in the past, however, to form a close-knit community in their new California setting. Life was centered around the farm, school and church… There were farms to be developed and crops to be raised including new ones which did not always succeed…

The early years were an experimental period, difficult and trying. However, there was a new industry just in its infancy, to which the German-Russians soon adapted with their industrious zeal: commercial wine production.

Other producers followed, but for most the vineyards and winemaking were not dominant concerns, to compare to wheat production and stock raising. Lodi area wine and brandy by 1889 were said to be among the best produced in the United States, even carried to eastern states by the Transcontinental Railroad, and profiting from contemporary root disease problems of European vineyardists. Thus the new German-Russian settlers were not originators in the wine industry but came at a perfect time to plunge into it and participate in its explosive growth.

912 class of Victor School, primarily serving east side Lodi’s German-Russian community; at the time, consisting of 62 students, from first to eighth grade. Lodi News-Sentinel.

In 1898, on thirty acres south of Lodi, now the corner of Church Street and Kettleman Lane, Wilhelm “Columbus” Hieb planted a vineyard. He confirmed the findings of the California State Board of Horticulture’s annual report of 1892, that the sandy loam south of the Mokelumne River was well adapted to the cultivation of vines and fruit trees. He was running his own commercial wine operation by 1906, giving him the distinction of being one of the first to operate a vineyard on that scale in the district. His example caught on like wildfire. Soon nearly all of the newly arrived German-Russians were planting vineyards, as well as alfalfa and fruit orchards.

They are located almost exclusively east of Lodi in the Alpine-Victor sectors, Acampo, the Live Oak district, and eventually as far east as Clements. As a result of acquiring large acreages and employing the most modern methods of irrigation, especially in tapping groundwater resources, they brought their crops to high levels of productivity.

Late 1920s photo of the John Nies family. Lodi Historical Society.

When George Tinkham published his notable History of San Joaquin County in 1923 some of his examples of successful vineyardists, exemplifying new and admirable techniques, were from this group:

-

- Gottfried Handel—40 acres in vines, 18 in alfalfa, near Lodi. His irrigation pumping plant was one of the largest in the country at that time.

- Abraham Bechtold—three farms totaling 36 acres, with pumping plants on each.

- C.H. Fink—his 56-acre ranch used water from the Lodi District pumping plant.

- William Preszler—37 acres near Victor, using pumps and other modern equipment to increase production.

- Peter Heil—a 25-acre vineyard with pumping stations using a ten-horsepower motor and cement pipes.

November 11, 1918 gathering under Lodi’s Mission Arch on Armistice Day: The banner (“For 100% Americans”) was hung earlier during WW I by the German-Russian community to proclaim their pro-American standing; an effigy of the German Kaiser hangs from the Arch, and the citizens are wearing face-masks reflecting health measures taken during the 1918 Spanish influenza. Lodi Historical Society.

Others identified by Tinkham included Jacob G. Handel, G. Handel, Charles J. Bender, John J. Schmiedt, John Bechtold, George Preszler, Theopold Kirschenmann, and Henry G. Mettler. The German-Russians did not merely participate in the expansion of grape growing and production; in fact, they were a dominant force through their extensive utilization of progressive irrigation techniques and other modern methods. The Woodbridge Vineyard Association and the Community Winery of Lodi were operations to which the Lodi German-Russians contributed notably.

The German-Russian group continued to grow as the years passed and the evidence mounted of good living to be had in the Lodi area. By 1920 there were an identified 845 here, second in size in California only to the concentration in the Fresno–Reedley area.

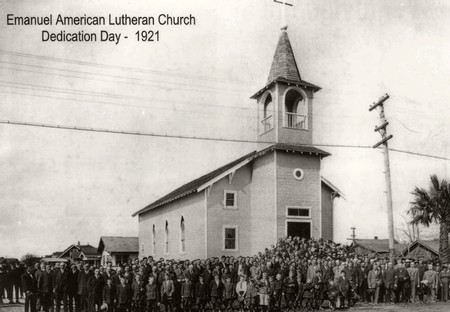

1921 commemorative photograph of the Lodi German-Russian community’s Emanuel Lutheran Church; notwithstanding the proudly declared “American” nomenclature, it would not be until 1941 that services were spoken in English rather than German. Lodi News-Sentinel.

Enduring impact on Lodi’s winegrowing industry

There were, in fact, larger populations of German-Russians in cities such as San Diego, Los Angeles, Merced, Garden Grove, and Fresno (re zipatlas.com); but in a small city like Lodi—a population growing from 1,500 to 6,788 between 1900 and 1930—their contributions carried more weight.

Henry and Elizabeth Schnaidt—the great grandparents of Harney Lane Winery owner Jorja Lerner, née Jorja Mettler—were German-Russian immigrants who planted the family’s first vineyards on the east side of Lodi in 1907. Courtesy photo.

Today, vineyards and wineries associated with German-Russian families such as Kirschenmann, Schmiedt, Mettler, and others are considered among the most prestigious in the appellation. They were not the first settlers to celebrate the riches of Lodi farmland. Indeed, there were many others who came before them who were already predicting that the region was bound to become the most productive in the United States. Lodi is not “Napa Valley,” or “Sonoma,” but there is a lot to be said for the fact that there are more acres of fine wine grapes in Lodi than those other two regions combined, or all of the states of Oregon and Washington combined.

Nor do German-Russians have a monopoly on reverence for farming or the land. Yet it would not be a stretch to say that it is the fundamental character of German-Russians—the intertwining of work ethic with religiously ingrained devotion, the sense of long-term and orderly planning, and especially the credence put on a family, legacy, generations, succession, social contract, and other values overtly or subtlely woven into grower-composed codifications such as LODI RULES for Sustainable Winegrowing—that have helped keep the region in good stead over the past 125 years.

Recent photo of own-rooted Zinfandel in Kirschenmann Vineyard, one of California’s most prestigious old vine plantings, originally planted in 1915 on Lodi’s east side by the Kirschenmanns, one of the more prominent of the extended German-Russian families transplanted from the Dakotas in the early 1900s.

Lodi remains an agricultural community for reasons far beyond reason—at least considering the urbanization of neighboring Sacramento, Stockton, and the ever-widening circumference of the Bay Area that one might assume should have swallowed this region long ago.

Where would the Lodi winegrowing industry be, you might ask, without the collective ethos of groups such as the German-Russians? In all likelihood, in not quite as good a place—if farming, sustainability, familial heritage, and emblems such as old vines are valued above all else.

2011 photo of Wanda Woock—author of Jessie’s Grove and great-grandaughter of pioneering Lodi farmer Joseph Spenker—with her late husband Al Bechthold. While the Woock and Bechthold families represent Lodi’s historic German-Russian lineage, they might be better known today for Bechthold Vineyard, revered as the oldest planting of Cinsaut grapes (planted in 1886) in the world.

Continued from Story of an appellation—Part 5, history of Lodi labor and Grape Festival memories

Read the rest of the series below:

Story of an appellation—Part 4, the Lodi populace from the 1800s to today

Story of an appellation—Part 3, Lodi’s sister grapes and era of grape packers and cooperatives

Story of an appellation—Part 2, origin of Lodi as a city and agricultural region

Story of an appellation—Part 1, the first stewards of the land that would become Lodi

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorials to The Tasting Panel magazine, crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media, and is the author of the new book “Lodi! A definitive Guide and History of America’s Largest Winegrowing Region.”

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.