The invasive vine mealybug (VMB) is a carrier of grapevine leafroll-associated viruses (GRLaV) and, therefore, among the most damaging grapevine pests in the United States. While a variety of chemical and biological controls have been developed to target the VMB, none are capable on their own of effectively limiting the spread of GRLaV. This work was undertaken to see whether mating disruption – a strategy of using pheromones to radically decrease VMB mating success in the vineyard – on its own and in combination with insecticides, offers a better way of controlling VMB and GRLaV in Lodi vineyards.

The invasive vine mealybug (VMB) is a carrier of grapevine leafroll-associated viruses (GRLaV) and, therefore, among the most damaging grapevine pests in the United States. While a variety of chemical and biological controls have been developed to target the VMB, none are capable on their own of effectively limiting the spread of GRLaV. This work was undertaken to see whether mating disruption – a strategy of using pheromones to radically decrease VMB mating success in the vineyard – on its own and in combination with insecticides, offers a better way of controlling VMB and GRLaV in Lodi vineyards.

Mating disruption relies on the peculiar biology of the VMB: winged adult males locate and fly to wingless adult females to mate only by virtue of sex pheromones that the females emit. When the local environment is overloaded with a synthetic version of this pheromone (Lavandulyl Senecioate), the synthetic signal masks the female-associated one, males are unable to efficiently locate females, and mating is disrupted. Field trials in 2011 and 2012 in Napa County demonstrated that mating disruption reduces GRLaV-associated grapevine damage. The number of pheromone dispensers needed throughout the vineyard – one hand-placed every two to three vines (250 per acre) – made this strategy expensive, time-consuming, and therefore impractical for industry use. We were attempting to devise ways of saturating a vineyard with an effective amount of pheromone in less expensive and labor-intensive ways.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Additional information about mating disruption as a form of pest control can be found in the pest management chapter (page 187) of the Lodi Winegrower’s Workbook.

__________________________________________________________________________________

The project involves collaborators across the state conducting a variety of field trials. We investigated two alternate pheromone dispensers – puffer spray cans (“puffers” ) and plastic dispensers – and evaluated their efficacy based both on the extent of VMB damage (the practical outcome) and the way in which pheromones were distributed in the vineyard (the theoretical explanation for our visible results). In Lodi, we specifically looked at the efficacy of puffer cans. In Fresno, we tracked the VMB response to pheromone release to better understand VMB flight patterns.

Figure 1. The puffer can as deployed in the vineyard (left), and with the lid open exposing the canister of pheromone and the timer (right)

Puffers are spray cans controlled by programmable chips, together contained in a brown plastic housing that resembles a small bird box (Figure 1). Based on successful application against moth pests affecting other crops, we know that they need be placed at a density of only two per acre for effective pheromone coverage. We tested their efficacy against VMB in a commercial vineyard known to have VMB problems in Denair, CA. Treatment blocks were hung with two puffers per acre – each on a 1.8m stake above the canopy – plus a perimeter of conventional dispensers that emitted about 1/8th as much pheromone as the puffers. Even though both the treatment and control blocks received the same delayed dormant application of chlorpyrifos and a post-harvest application of spirotetramat (Movento, Bayer CropScience), pheromone-treated blocks treated were less severely affected by VMB damage. Fewer mealybug males were also caught in pheromone-baited traps in treated blocks than in untreated blocks. VMB cycle through five to seven generations per year, so the number of males caught in traps primarily represented the males’ ability to home in on sources of pheromones – we assume that if they cannot effectively locate traps, they can also not effectively locate females – rather than an absolute reduction in VMB number from week to week as the traps were collected.

We also looked more specifically at how many dispensers and how much active ingredient per dispenser can effectively suppress VMB mating (Figure 2). Dispenser coverage and active ingredient contents for VMB suppression in vineyards have been based on patterns found effective against other pests; no one has determined the minimum effective coverage specifically for the VMB. A set of field trials from 2010 to 2012 in San Luis Obispo County demonstrated that conventional dispensers (each containing 150 mg pheromone) set at either the customary 250 dispensers per acre or at 188 dispensers per acre strongly and significantly reduced the number of VMB males caught in pheromone traps; dispensers set at 125 or 50 per acre, however, did not significantly reduce trap counts.

__________________________________________________________________________________

The information presented in this article may be useful for growers looking to score points toward LODI RULES certification. See the Pest Management chapter (Chapter 6).

__________________________________________________________________________________

Based on those results, we conducted a second set of trials in a vineyard east of Denair in which we attempted to evaluate whether fewer dispensers per acre could be effective if each contained more pheromone. In other words, we asked whether saturating the vineyard with pheromone was sufficient, or whether a high density of pheromone emitters was crucial. We expected that effective control would depend on many pheromone sources. We were surprised to find that all of our treatments significantly reduced VMB damage compared with untreated blocks (Table 1). There was really no clear pattern within the pheromone treatment blocks (e.g., rate vs load vs dose). Treatments with the highest density of pheromone card dispensers (250 per ac) had 7.22% damage and 9.44% damage at loads of 25 and 37.5 mg ai, respectively. Whereas, treatments with 175 dispensers per acre had even lower damage levels, than the higher rate, which is contrary to our expectations. These plots were 99.44% and 98.33% clean in plots with loadings of 25 g/acre and 37.5 g/acre respectively. What is important to note is that all mating disruption plots had lower damage than the control, and in a vineyard that was highly infested in the previous years, this represents a remarkable level of insect control. (Our grower cooperator reported that no additional insecticides were used at the site and that all treatments received the same amounts of insecticides previous to the study and during the study.)

__________________________________________________________________________________

Table 1. Effect of vine mealybug damage to wine grape clusters at 16% TSS as affected by dispenser hang rate and active ingredient amount per dispenser.

| Rate*

0 |

Load**

0mg |

Dose***

0.00g |

% No Damage 71.67 90.00 87.22 99.44 98.33 92.78 90.56 |

% Little Damage 21.67 5.56 10.56 0.56 1.11 5.00 7.22 |

% Damaged

21.67 |

% Unmarketable 0.00 1.11 1.11 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

* Rate is the number of dispenser per acre

** Load is the amount of ai per dispenser (in mg per dispenser)

*** Dose is the total amount of ai delivered per acre (Rate x Load)

__________________________________________________________________________________

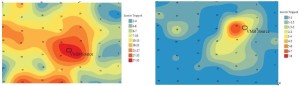

We will be able to design more efficient, effective patterns of pheromone dispersal if we better understand the flight behavior of the male mealybug: how far will a male fly to locate a pheromone-emitting female, and how do wind conditions affect flight behavior? We artificially introduced VMB into a pistachio orchard (to avoid having other mealybugs interfere with the study) at the Fresno State campus and placed 50 pheromone-baited traps over 20 acres in a grid pattern. Based on trap counts collected three times daily, we mapped out male mealybug movement across the orchard over time (Figure 3). Our results show that, even in ideal conditions – warm, low wind – males did not move toward pheromone sources but were instead caught near their initial release site. Male VMB do not appear to be strong fliers.

We conclude that the male VMB insects are not strong flyers, and while there may have been pressure to remain near the live female source (e.g., the colony placed into the field) the study showed the impact of dispensers placed in a field where there were few heavily infested vines. An ideal dispenser density should be around 175 dispensers per acre regardless of loading to have efficient control.

Figure 3. Over the three trials (A – July 25-August 5, B – October 12-22), flights of male mealybug were substantial and despite warm morning temperatures and low wind velocities the insects did not orient to upwind pheromone point sources. Adult males were consistently caught in the vicinity of mealybug source and rarely upwind from that source on any observation day. With only one exception, the traps closest to the mealybug source had the highest numbers of captured males. We conclude that the males are not strong flyers, and while there may have been pressure to remain near the live female source (e.g., the colony placed into the field) the study showed the impact of dispensers placed in a field where there were few heavily infested vines.