Welcome to part two of a three part Coffee Shop series on understanding and managing trunk diseases in Lodi vineyards. In part one of this series we discussed how to identify trunk canker diseases, practices to prevent them, and management strategies for new and established vineyards. Today, we will dig deeper into the subject and learn about the diseases’ historical development in California, how the disease impacts vineyards, it’s symptoms, how it spreads among grape vines and across crops, and we will also identify some resistant winegrape cultivars. These two Coffee Shop articles were written by Kendra Baumgartner, PhD and Renaud Travadon, PhD, with grant funding from the USDA-NIFA Specialty Crop Research Initiative

Welcome to part two of a three part Coffee Shop series on understanding and managing trunk diseases in Lodi vineyards. In part one of this series we discussed how to identify trunk canker diseases, practices to prevent them, and management strategies for new and established vineyards. Today, we will dig deeper into the subject and learn about the diseases’ historical development in California, how the disease impacts vineyards, it’s symptoms, how it spreads among grape vines and across crops, and we will also identify some resistant winegrape cultivars. These two Coffee Shop articles were written by Kendra Baumgartner, PhD and Renaud Travadon, PhD, with grant funding from the USDA-NIFA Specialty Crop Research Initiative

Most vineyards in California are likely infected with trunk diseases (wood-canker). The main diseases are Botryosphaeria dieback, Esca, Eutypa dieback, and Phomopsis dieback. The infections are chronic and accumulate over time. Infected vines become less profitable with each additional infection, to the point at which the entire vineyard must be replanted. In this way, trunk diseases significantly limit vineyard longevity. Follow this guide to identify trunk diseases in your vineyard.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Mark your calendars for the Managing Vineyard Trunk Disease Symposium on November 5th from 9AM-1PM at Burgundy Hall. Three hours of CDFA continuing education. Lunch will be served. Click HERE for more information.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Historical background

Figure 1 Extensive ‘gummosis’ on the trunk of an apricot tree with Eutypa dieback. Photo by R. Travadon.

It was not until 1959 that a wood-canker disease was recognized as a serious problem in apricot orchards in Santa Clara County. Symptomatic trees showed extensive ‘gumming’ near cankers around branch scars (Figure 1). A more severe symptom was dieback of branches (Figure 2) and sometimes of entire trees. In the laboratory, isolations of the fungus Eutypa lata suggested that the same disease described as Eutypa dieback of apricot in South Australia was present in northern California. Subsequent orchard surveys revealed the presence of the disease in multiple counties. Soon after, in the early 1970s, the focus shifted to vineyards, where Eutypa dieback was reported a major problem in northern San Joaquin, Livermore, and Napa Valleys. Recent, comprehensive surveys have now revealed the disease in vineyards of the North and Central Coasts, the northern San Joaquin Valley, and the Sacramento Valley.

Impact of the disease in vineyards

Upon infection of pruning wounds by wind-dispersed spores, the pathogen colonizes the permanent woody structure of the vine (trunk, cordons, spurs, canes), causing a chronic infection of the wood. Cumulative yield losses from dead spurs and cordons reduce the productive lifespan of a vineyard. Yield losses can reach 94% in severely-symptomatic vineyards. The economic impact of annual Eutypa losses in California wine grapes (in combination with Botryosphaeria dieback) has been estimated at 14% of the gross producer value. In order to reduce this figure, we are conducting a research program funded by a grant from the USDA-NIFA Specialty Crop Research Initiative. One objective is to determine the costs and returns of adopting preventative practices in newly-established vineyards.

Disease symptoms

Eutypa lata is technically a ‘soft-rot fungus’, which produces enzymes that degrade the wood. After wood colonization by the pathogen, a canker forms near the infected pruning wound. Cross-sections of infected spurs, cordons, and trunks reveal wedge-shaped, rotted areas of the wood (Figure 3). In the canopy of infected vines, look for stunted shoots with small, cupped, chlorotic, and tattered leaves, in late April to early May (Figure 4). Flowers on these shoots frequently do not develop into clusters. These foliar symptoms result from the transport of toxic compounds produced by the pathogen in the wood and transported to the leaves through xylem vessels. These foliar symptoms take a long time to develop — usually 3-8 years after infection. This long delay between when the disease becomes established in the vineyard and when we are first alerted to its presence means that the preventative controls for Eutypa dieback (and other trunk diseases like Botryosphaeria dieback, Esca, and Phomopsis dieback) are often not used until it is too late.

Disease spread

The disease spreads in the form of sexual spores (ascopores). These spores are produced on a dead cordon or trunk of an infected vine; spore production takes several years from the time of infection. In northern California, the spores are produced primarily in infected vineyards, and in apricot and cherry orchards. These spores are less commonly found in pear, apple, and almond orchards, as well as in a few native plant species (California buckeye, big leaf maple, willow) and ornamentals (oleander). Spore production has been monitored with spore traps in past studies, and is known to occur in geographic areas with annual rainfall > 13.5 inches. Spore release requires a minimum of 0.08 inches in a given rain event. Spores are transported by wind and may cause further pruning wound infections, provided they land on such wounds. Because rainfall and the spread of Eutypa dieback coincides with dormant-season pruning, it is critical to prevent infection through delayed/double pruning or pruning-wound protection.

Epidemiology in multiple host plants

Early disease surveys identified spores in apricot orchards, that were then located in the eastern Bay Area. Because similar efforts in the Central Valley failed to find spores, spores infecting vineyards in the Central Valley were assumed to originate from the east Bay. More recent studies suggest that most sources of spores are instead local vineyards and orchards. That said in rare instances, a few spores from an infected vineyard or orchard can potentially be carried on air currents across large distances, for example from coastal areas to the Central Valley.

Figure 4. Foliar symptoms of Eutypa dieback, which were reproduced in the greenhouse after 11 months of infection. Photo by R. Travadon.

Our recent work (funded by a grant from the American Vineyard Foundation) focused on the prevalence of Eutypa dieback in vineyards, apricot and cherry orchards, and willows in the counties of San Benito, Solano, and Napa. Our results (Table 1) clearly show that Eutypa dieback is much more prevalent in vineyards and orchards, than in willow trees in riparian areas surrounding vineyards. Indeed, after examining the prevalence of the pathogen from a total of 725 plants (including four hosts at three locations), prevalence tended to be higher in cultivated crops. We found levels of 31 to 46% in grape and apricot, 0 to 47% in cherry, and only 4 to 25% in willows. These findings suggest that cultivated crops are likely more important sources of the pathogen than willow.

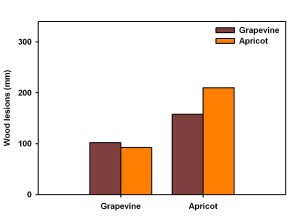

In addition, we examined the genetic similarities among Eutypa lata strains isolated from these different hosts. It is now clear that pathogen populations from multiple hosts are genetically similar. From these results, we can say that the disease spreads among grape, apricot, cherry, and willow, with no preference for a given host plant. Additional evidence that bolstered this finding came from inoculation assays in the greenhouse. When we inoculated strains originating from either grape or apricot to grape and apricot, we measured similar levels of wood and foliar symptoms (Figure 5).

__________________________________________________________________________________

Table 1. Prevalence of Eutypa dieback in vineyards, orchards, and riparian areas in three counties of California

| Host Plant

Grapevine Apricot Cherry Willow |

County

San Benito San Benito San Benito San Benito |

City

Hollister Hollister Hollister Hollister |

Plants examined

48 47 40 54 |

Prevalence (%)

44 36 47 11 |

__________________________________________________________________________________

Grapevine cultivar resistance to Eutypa dieback

Figure 5. Average length of wood lesions measured in grapevine and apricot plants, which were inoculated with Eutypa strains originating from grapevine (brown) or apricot (orange). Wood symptoms were measured 14 months after inoculation in the greenhouse. Results suggest no host specificity, with all strains able to cause similar levels of wood symptoms in each host. That said, apricot is more susceptible to wood degradation than grapevine.

Several cultivars have been ranked according to their level of susceptibility to Eutypa dieback, based on field observations of the foliar symptoms. For example in France, ‘Merlot’, ‘Semillon’, and ‘Aligote’ are considered resistant, whereas ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Grenache’, and ‘Chasselas’ are considered very susceptible. Part of our research (funded by a grant from USDA-NIFA Crops at Risk) focused on screening cultivars commonly grown in California for resistance to Eutypa wood and foliar symptoms. In comparing wood symptoms, we found similar levels of Eutypa resistance among the following cultivars:

- Cabernet Franc

- Cabernet Sauvignon

- Chardonnay

- Merlot

- Riesling

- Petite Syrah

In contrast, Thompson Seedless, the only table-grape cultivar examined, was more susceptible. Even more susceptible than Thompson Seedless were native, North American Vitis species (such as V. arizonica and to a lesser extent V. aestivalis, V. riparia, and V. cinerea). A new development in our research is a rapid assay for comparing cultivars in terms of foliar symptoms, which are expressed more quickly than the assay for wood symptoms. Our findings from both assays confirmed that there is variation for resistance to Eutypa foliar symptoms in grape germplasm collections, and such variation in disease resistance could be used to breed grape cultivars with enhanced resistance to Eutypa dieback.

Managing Eutypa dieback in vineyards

There are no curative fungicides to eradicate wood cankers. Once a grapevine shows symptoms, the only post-infection options are:

- Vine surgery – attempt to cut out diseased tissues and retrain new cordons/canes from the healthy part of the trunk.

- Uproot symptomatic vines and replant.

Effective control of Eutypa dieback and other trunk diseases thus relies mainly on the prevention of pruning wound infections. Prevention is by far the most effective approach. It is best to prune during the time when pruning wounds are the least susceptible to infection (end of the dormant season) and when spore production is low (no rain). Another preventative approach is the applications of fungicides Topsin and Rally to protect pruning wounds. Detailed recommendations on trunk disease diagnosis and preventative practices to adopt in young vineyards and in diseased vineyards can be found in our recent Coffee Shop article on management of trunk diseases (https://www.lodigrowers.com).