AUGUST 3, 2020. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

In most grape purchase contracts, soluble solids are the principal criteria for scheduling harvests. Soluble solids are critically important for wineries because their concentration in the fruit determines potential wine alcohol and wine style. They are, actually, so important that failure to deliver grapes within the range of desirable soluble solids is the reason for price discounts.

Soluble solids, sugars, their production, and their uses in vines.

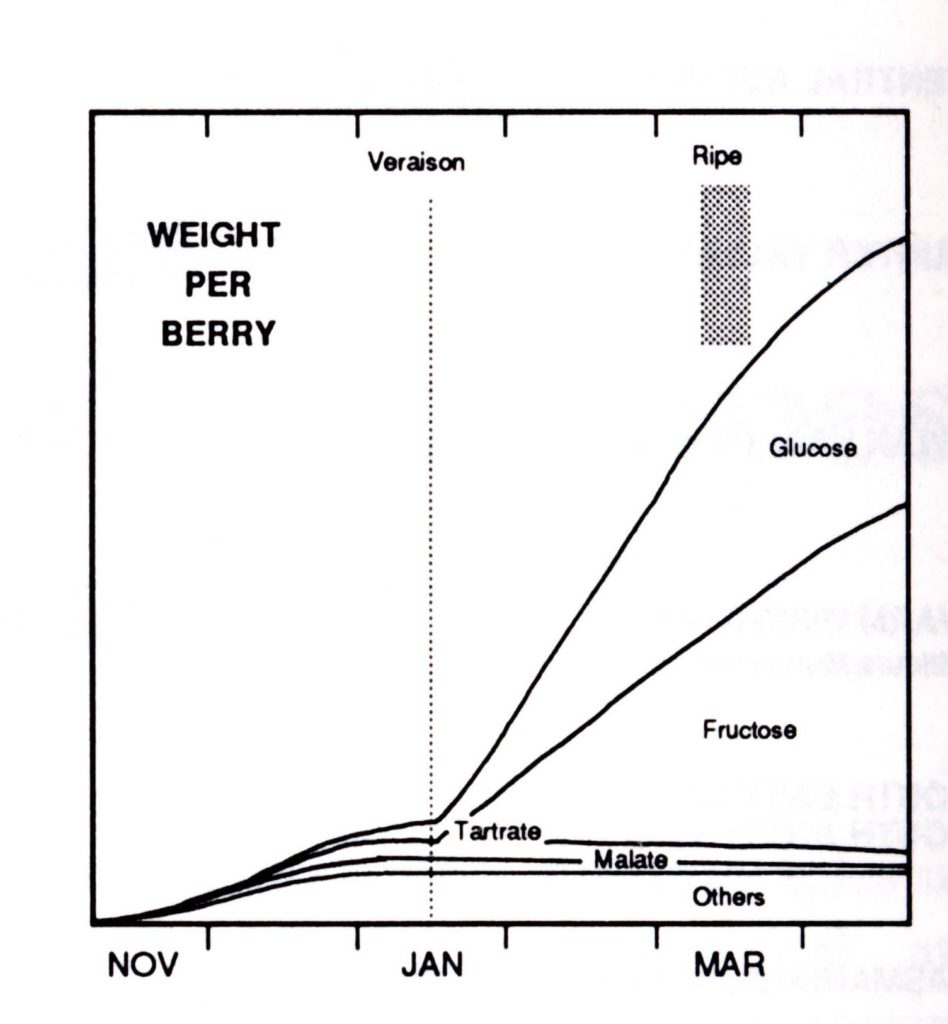

At maturity, the sugars fructose and glucose are by far the most plentiful soluble solids in winegrapes. In fact, the content of these carbohydrates is about 14 times greater than the content of the next most plentiful soluble solids, tartaric and malic acid, and 22 times more plentiful than the most abundant mineral nutrient, potassium (Figure 1). Due to their preponderance, those of us involved in the winegrape industry use the terms soluble solids and sugar interchangeably.

Figure 1. Solute accumulation during berry development.

Figure 1. Solute accumulation during berry development.

(Source: Coombe (1975) and Hamilton and Coombe (1992))

In grapevines, sugar production occurs primarily in leaves in the sunlight-driven metabolic process known as photosynthesis. This process combines carbon dioxide from the air with water from the soil to form sugars and oxygen, which is released into the atmosphere (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The basic photosynthesis reaction. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Figure 2. The basic photosynthesis reaction. (Progressive Viticulture©)

In addition to accumulating in berries and imparting sweetness therein, sugars are raw materials for other organic molecules produced in grapevines. Normally, a portion of the sugars produced each growing season is stored in woody vine tissues to support growth early in the next season and sometimes, these reserves also contribute to accumulating berry sugars during fruit maturation.

Obviously, producing ample sugar is one of the primary goals of grape growing. This goal is achievable only if sufficient leaves are grown and their function preserved. Listed below are several measures to promote sugar production in your vines and accumulation in your winegrapes.

Design and develop your vineyard for sugar production.

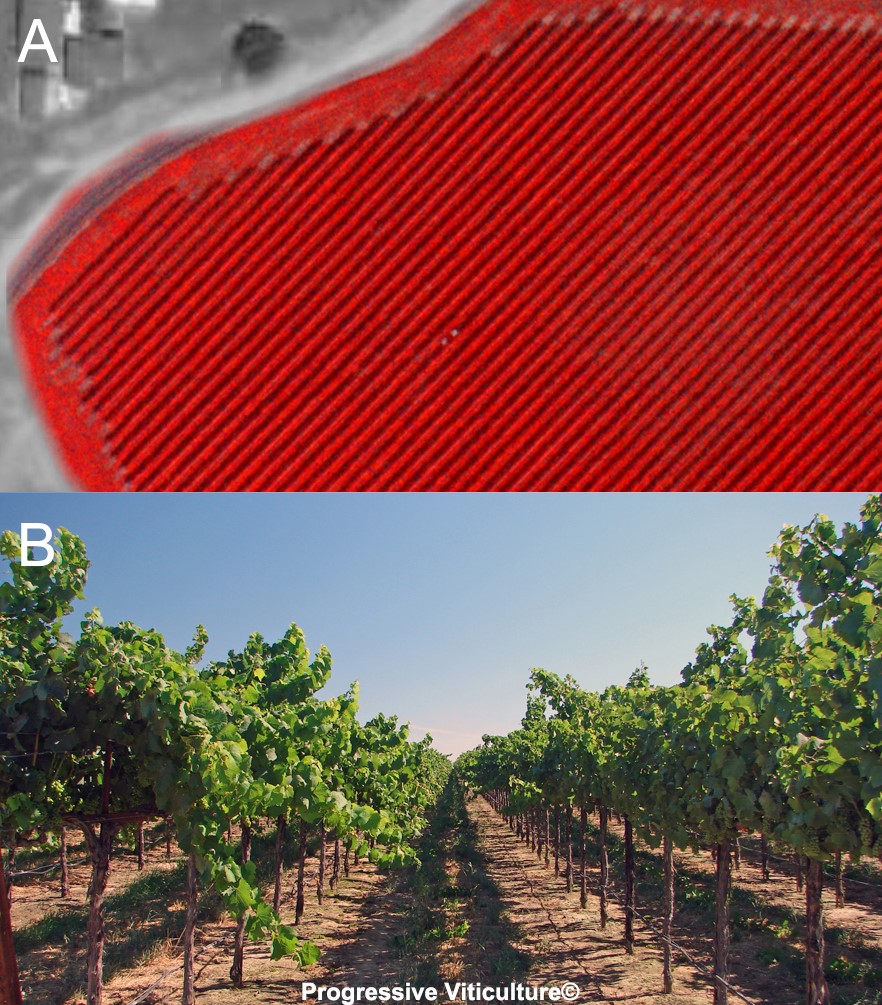

Begin with CDFA-certified plant material or other vines known to be tested for pathogenic viruses, as most inhibit sugar accumulation. Use a spacing-training-trellising-pruning system that promotes balanced fruit and foliage growth, allows room for complete canopy development, and facilitates maximum exposure of leaves to sunlight (Figure 3). Complete canopy development typically involves fourteen to twenty leaves for a shoot bearing two clusters. These parameters accommodate normal decreases in photosynthetic rates as leaves age during ripening, as well as providing a small buffer for limited leaf damage.

Figure 3. Canopies on a Wye trellis typically have a high proportion of exterior leaves, as viewed from above in an infrared aerial image (A) and on the ground (B) in a Chardonnay vineyard. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Figure 3. Canopies on a Wye trellis typically have a high proportion of exterior leaves, as viewed from above in an infrared aerial image (A) and on the ground (B) in a Chardonnay vineyard. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Apply sufficient resources for full canopy development and optimized photosynthesis.

Early in the growing season, ensure adequate soil moisture to grow complete canopies. Irrigation may be required during dry winters and springs, for soils with low moisture holding capacities, and for vineyards with a large number of leaves per acre. Refrain from regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) schedules until after full canopy development.

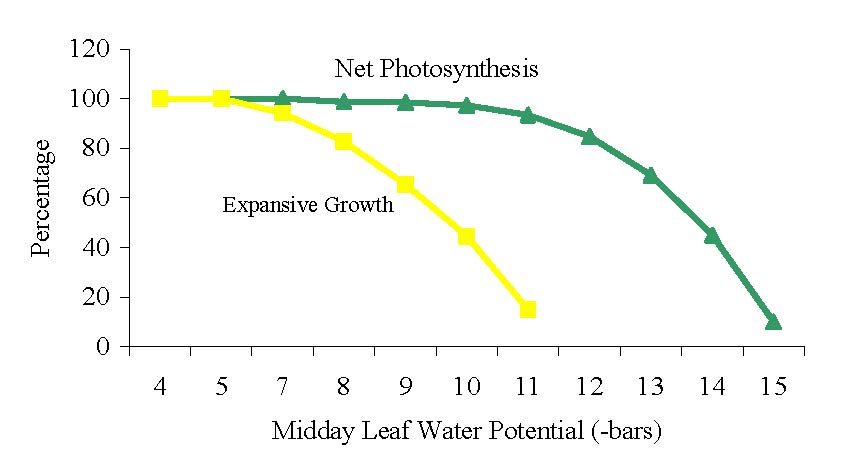

As stated above, soil water is a raw material for photosynthesis. Accordingly, substantially limiting available soil moisture and imposing severe water stress on vines inhibits sugar accumulation in berries. To avoid such stress, use regulated deficit irrigation schedules that maintain moderate vine water stress, which is evident as arrested shoot elongation, healthy, aged, and hardened leaves, and timely stem ripening. With such schedules, midday leaf water potentials remain between -10 and -13 bars (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The effect of water stress measured as midday leaf water potential on photosynthesis.

Figure 4. The effect of water stress measured as midday leaf water potential on photosynthesis.

(Source: Prichard, et. al (2004))

Normal photosynthesis and sugar production involves most of the 13 essential mineral nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, potassium, magnesium, iron, manganese, and copper. During ripening, the high demand for potassium sometimes inhibits sugar accumulation in berries, especially where there is a large amount of fruit relative to foliage. Clearly, ensuring a balanced supply of mineral nutrients in-season is important when farming for sugar and we ought to fertilize vineyards correspondingly.

Promote leaf exposure to sunlight.

Leaves in full sunlight have the potential for maximum sugar production. These leaves, which reside on the canopy exterior, also absorb about 90% of the sunlight that strikes them and transmit only about 10% (Figure 5). As a result, photosynthetic activity and sugar production is much lower in the second leaf layer. Leaves shaded by two or more leaf layers consume more sugars than they produce.

Figure 5. A well exposed leaf absorbs about 90% of incident sunlight and transmits about 10% to leaves or clusters behind it. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Figure 5. A well exposed leaf absorbs about 90% of incident sunlight and transmits about 10% to leaves or clusters behind it. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Obviously, leaf shading is viticulturally inefficient, involving an investment of vine resources for little or no return. As mentioned previously, leaf exposure depends on the vineyard design. However, even canopies of well designed vineyards often require some fine tuning through practices such as shoot thinning, shoot positioning, and basal leaf and/or lateral shoot removal.

Conserve leaves and leaf function.

For sugar production, it is nearly as important to maintain healthy leaves, as it is to grow the proper number of leaves. To this end, carefully schedule and apply canopy management practices, such as hedging and leaf removal, to avoid early and excessive defoliation and compromised sugar synthesis. In addition, protect leaves from serious damage leading to restricted photosynthesis or leaf area loss, such as damage from insect pests (leafhoppers, mites, thrips, worms), diseases (powdery mildew), stresses (heat, light, and water), and nutrient deficiencies and mineral toxicities.

Where canopies are insufficient, adjust the crop load to restore balance between leaf area and fruit.

Shoot growth commonly ceases shortly after fruit set. At that time it is clear if canopy development is sufficient for timely sugar production, as described above. If it is not, thin clusters as soon as possible to restore balance.

This is a modified version of an article published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services September, 2005 newsletter. The article was updated for this blog post.

Further Reading

Coombe, BG. Development and maturation of the grape berry. Aust. Grapegrower & Winemaker. 12:60, 66. 1975.

Grant, S. Five-step irrigation schedule: promoting fruit quality and vine health. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 21(1): 46-52 and 75. May/June 2000.

Grant, S. Balanced soil fertility management in wine grape vineyards. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 24 (1): 7-24. May/June 2002.

Grant, S. Regulated deficit irrigation, parts I and II. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (lodigrowers.com). July 18 and August 04, 2014.

Hamilton, RP; Coombe, BG. Harvesting of winegrapes. In Coombe, BG; Dry, PR (ed.). Viticulture. Volume 2 Practices. Winetitles, Adelaide, 1992.

Keller, M. The science of grapevines. Academic Press, Burlington, MA. 2010

Marschner, H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. Academic Press, London. 1986.

Mullins, MG; Bouquet, A; Williams, LE. Biology of the grapevine. Cambridge University Press. 1992.

Prichard, TL; Hanson B; Schwankl, L; Verdegaal, P; Smith, R. Deficit irrigation of quality winegrapes using micro-irrigation techniques. University of California Cooperative Extension, Department of Land, Air, Water Resources, University of California, Davis. 2004.

Salisbury, FB, Ross, CW. Plant physiology. Wadsworth, Belmont, Calif. 1978.

Smart, R; Robinson, M. Sunlight into wine: A Handbook for Winegrape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1991.

Winkler, AJ, Cook, JA, Kliewer, MK, Lider, LA. General Vitic. Berkeley, Univ. Calif. 1974.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.