MONDAY, JULY 31, 2023. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Featured image: 2022 harvest in Lodi, a wine region in which warm climatic conditions are utilized to optimal advantage.

Boy, it’s been a hot July. Everywhere. This, ironically, follows an unusually cool month of June in Lodi wine country. In fact, a cooler than normal first six months of the year. Whatever the case, everyone’s talking about climate change, even outside political contexts. It doesn’t matter what you think. There have been significant shifts in climate.

In respect to viticulture, during the past ten years, no one has written more about the impact of climate change on the winegrowing industry than Dr. Gregory V. Jones, a renowned Oregon-based research climatologist who is now the CEO of Abacela Winery (an industry-leading Umpqua Valley estate founded by the professor’s parents, Earl and Hilda Jones). For constantly updated, fascinating reads, look up Dr. Jones’ highly detailed Weather and Climate Summary and Forecast.

Dr. Jones recently wrote to me, complimenting a lodiwine.com post from earlier this year alluding to Köppen climate classifications, which was couched in a discussion of Lodi’s Mediterranean climate (re Delineations of Mediterranean climate in Lodi and the rest of the world).

In his email, the professor also attached a snippet of a scholarly work recently published on climate classification as it pertains to wine growing all around the world. Wrote Jones: “Back in 2009-2010, a couple of students of mine and I did a global assessment of Köppen climate types using the best digital database of wine region boundaries and raster data of Köppen climates worldwide.

Dr. Greg Jones, is a renowned climatologist, and CEO of Abacela Winery in Southern Oregon’s Umpqua Valley.

“The main point in this analysis and in our refresh of this work,” added Jones, “is that Mediterranean climate types are actually quite limited in the world of wine, including in the actual Mediterranean basin.” Jones’s point is well taken: Most of the world’s finest wines are grown outside warm to hot climate zones classified as “Mediterranean.” As productive as warm to hot climate regions such as Provence, Southern Italy, Greece or (here on the home front) Lodi may be, they represent a smaller fraction of the entire world’s vineyards.

Following Jones’ lead, I found larger snatches of his recent research entitled Climate, Grapes, and Wine, posted in GuildSomm (August 12, 2015). One section starts with this question: “Is there an Ideal Climate for Wine Production?” This question is interesting to us, of course, because we grow grapes in Lodi, and we are always interested in where the Lodi winegrowing region fits on a global scale.

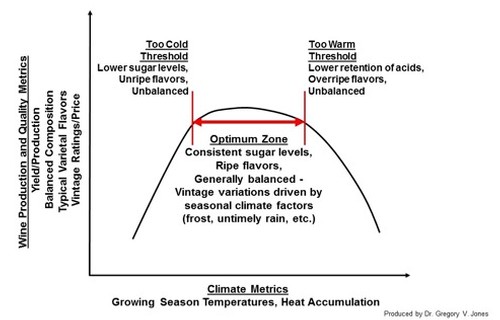

For all wine grapes (i.e., cultivars), write Jones, there is an “optimum zone” in which “a given cultivar will more consistently produce higher quality wine.” Although wine can be complicated stuff, “quality” is pretty much summarized as those made from grapes ripening with optimal “flavors” while retaining ideal levels of natural acidity.

In mid-July 2023, a slightly late véraison (i.e., annual changing of colors) among old vine Zinfandel, the grapevine that is emblematic of the Lodi appellation.

Winegrowing, of course, is also complicated. While soil, topography, and vineyard management are among the myriad factors determining how grapes are grown and the quality of wines made from those grapes, Jones states:

For all agricultural enterprises climate plays a dominant role in influencing whether a crop is suitable to a given region, largely controlling crop production and quality, and ultimately driving economic sustainability. In viticulture and wine production, climate is arguably the most critical aspect in ripening fruit to achieve optimum characteristics to produce a given wine style. For wine drinkers the most easily identifiable differences in wine styles come from climate: the general characteristics of wines from a cool climate versus those from a hot climate.

Varieties that are best suited to a cool climate tend to produce wines that are more subtle, with lower alcohol, crisp acidity, a lighter body, and typically bright fruit flavors, while those from hot climates tend to be bigger, bolder wines with higher alcohol, soft acidity, a fuller body, and more dark or lush fruit flavors.

The impact of climate on wine quality

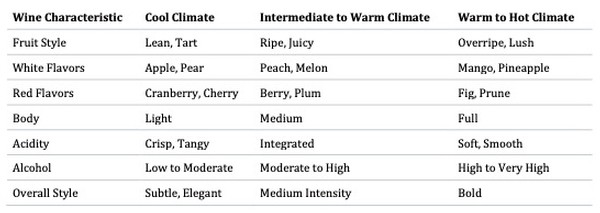

The following is a table of wine descriptors proffered by Jones, summarizing the role of climate as it pertains to wine styles and sensory attributes:

For our purposes, where does a region such as Lodi stand in this global assessment? Lodi, as a matter of fact, is a squarely Mediterranean climate region marked by temperatures falling under the “Warm to Hot” column of this table. Therefore, according to this chart, all Lodi wines are “overripe” or “lush,” whites taste like “mango, pineapple,” reds like “fig, prune,” alcohol is “high,” acidity “soft,” and overall style “bold.”

What this chart does not explain is why there are so many wines now grown in Lodi that actually taste the opposite; veering more towards sensory qualities found in the “Cool Climate” column. Lodi, for instance, is now well known for white wines made from the Albariño grape—wines that tend to be “lean” and “tart,” “light” in body, “low to moderate” in alcohol, and “crisp, tangy” in acidity.

In a lodiwine.com article posted just recently, there is a description of a Lodi-grown Riesling that has a “moderately fragrant, honeyed scent with a distinct sense of minerality, a core of fresh-cut lemon… a desert-dry white wine that is light as a feather (12.5% alcohol), lemony crisp yet silken fine while mildly grippy on the palate, making for long, persistent flavors.” On a sensory level, this particular white wine screams “Cool Climate,” but it’s not a cool climate wine. It is grown in Lodi. Made by a winemaker who is way too low-tech to employ smoke and mirrors.

2022 Mokelumne River-Lodi harvest of Zinfandel, a cultivar that theoretically is most easily adapted to warm climates.

Then there is Zinfandel, Lodi’s signature grape because there is more of it grown here than in any other region of California (approximately 40% of the state’s total production): Many of Lodi’s old vine Zinfandels fall very much in the “cranberry, cherry” fruit spectrum, and can be quite “subtle” and “elegant”—again, qualities associated with “Cool Climate.” In fact, when compared to riper, denser, more robust Zinfandels from other vaunted regions, such as Sonoma County, the finest Lodi Zinfandels taste rather light, lean, and even “feminine,” by comparison.

How can this be?

I asked one of our better-known winemakers, Markus Niggli of Markus Wine Co. Mr. Niggli is known for lighter-style white wines that seem to defy all assumptions of what warm climate wines are supposed to taste like. One of these wines is the Markus Wine Co. Nativo—the 2022 iteration of this wine consisting of Kerner (69%), Riesling (21%), and Bacchus (10%) grapes grown in Lodi’s Mokelumne Glen Vineyards. Year after year, this bottling is an airy fresh, citrusy crisp, almost ethereal dry white with subtle floral scents leaning more towards mineral than tropical fruitiness. Nothing like what Lodi, or any warm climate region, is supposed to produce.

Markus Wine Co.’s Markus Niggli with Carignan from an old vine Mokelumne River-Lodi block which he farms.

In Niggli’s opinion, “The generalizations about warm climate winemaking are just that—generalizations. They don’t account for specific places, like Mokelumne Glen, which is located on a low-lying site in the bend of a river. I can’t exactly explain exactly why we can make wines that go in a cool climate direction because I am not a climate scientist, a chemist, or a biologist. I’m a winemaker. I go into the vineyard, I see what it’s front of me and I taste the grapes.

“I can also say that there is a bag of acid in my winery that has barely been touched over the past fifteen years. We don’t have to acidify our wines. Our grapes ripen with plenty of natural acidity.”

With further prodding, however, Mr. Niggli offered something of an explanation for the disparity between what is perceived about warm-climate winegrowing and the actual truth about warm-climate winegrowing. According to Niggli, “We have also changed in terms of how we make wine. Many of us in the industry have stepped away from the super-high octane style of wines that were more popular ten, or fifteen years ago. We are picking grapes earlier than before, making it easier to bring in balanced crops. Whereas fifteen years ago we used to pick red wines at 26° or 27° Brix [i.e., sugar reading], 24° is now high for us. White wine grapes are picked at 21° to 22°, and we often don’t even get that much sugar. Retaining acidity, in this case, is never a problem.

In Lodi’s Mokelumne Glen Vineyards, ripening clusters of Kerner, a grape originally developed for the German wine industry but which seems to have easily adapted to Lodi’s Mokelumne River appellation.

Lodi has another well-known “Markus,” and that’s Markus Bokisch, owner/grower of Bokisch Vineyards. Mr. Bokisch chalks up the phenomenon of cool-climate grapes doing well in warm-climate regions primarily to decision-making. Says Bokisch, “Our experience in Lodi has entailed a downward shift in Brix levels. We used to pick Albariño at 22.5°, 23° Brix, but found when we picked at 21° you get beautifully crisp, lemon/tangerine/citrusy whites; maybe less stone fruit but lighter and fresher wines.” Acid-driven Bokisch Albariños did not happen because Lodi suddenly became a cooler climate region. “It has everything to do with Brix levels,” says Bokisch, “not climate classifications.”

Niggli adds still another point: “One thing many of the scientists may not get about Lodi is that we also have many old or ancient vines here, which can produce fruit up to 25° Brix and still retain ideal pH levels of 3.5. It’s almost a guarantee in a couple of my ancient vine blocks. Older vines are different, you get better grape balance from them. There are even old vine blocks where the issue is not having enough acidity, it’s too much acidity. To say that a warm climate always produces lower acid wines makes no sense.”

Lodi’s “other Markus,” Markus Bokisch of Bokisch Vineyards, in his Clements Hills-Lodi Miravet Vineyard, planted three Spanish grapes known for acid-driven cava (i.e., sparkling wines).

The relation of temperature (i.e., degree-days) to quality

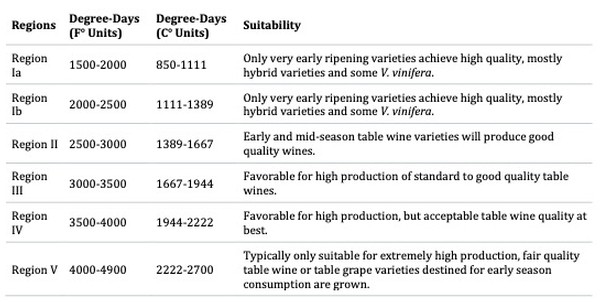

That said, the following is a second table cited by Jones pinpointing climate differentials based upon the “degree-day” formulation originally devised by UC Davis, now called the Winkler Index. In the recent revision (2010) of the Winkler Index by Jones’ team, the lower degree days of Region I are considered cool climates, and Regions IV and V are warm to hot climates:

In this second table, Lodi would fall under Region IV, producing wines described as “favorable for high production, but acceptable table wine quality at best.” Of course, it is the “at best” assessment that hurts the most. But not just for Lodi. There are, in fact, large swaths of Napa Valley and Sonoma County that fall in Region IV climate zones, as well as in other reputable wine regions such as Mendocino, Livermore Valley, Paso Robles, and the Sierra Foothills. Going by this chart, are all the warmer parts of these regions producing wines that qualify as “acceptable” at best? Indubitably, no. Many extraordinary, exquisitely balanced wines come from these areas. The pat summarization of warm climate wines is wrong, plain, and simple.

From Mr. Niggli’s perspective: “I can understand why people make generalizations about climate. Grapes are the base product. If you take grapes from all these regions and make them the exact same way, you may come out with some wines that are of ‘highest quality’ and other wines that are ‘standard’ or barely ‘acceptable.’

Mokelumne Riiver-Lodi Albariño, a cultivar that originated in the cool maritime Atlantic coast climate of Spain’s Rías Baixas yet nonetheless produces white wines every bit as light, bright, and acid-driven in Lodi’s Mediterranean climate.

“But what this generalization does not account for is what is done in a winery. I’m not talking about acidifying wines or adding water to lower alcohol [Markus Wine Co. wines are made with as little intervention as possible]. We grow grapes in a warm climate but can still take the wines in a cool climate direction. For example, I typically ferment my Kerner at 50°, which only accentuates the lightness and delicate character of the grape. When I ferment higher, at 60°, I don’t get that kind of character.

“To say cooler climate grapes are ‘good’ and warm climate grapes are ‘bad’ is really not much more than personal opinion. When someone says that I ask the question, ‘based on what?’ Old information or assumptions from twenty years ago? Everything is changing these days, not just the climate. I wonder, when is the last time any of these scientists tasted wines from Lodi?

“Yet the opinion persists that warmer climate grapes are not as good. These negative opinions hurt the industry. It hurts the growers’ grape prices. This is the kind of conclusion that takes five or six times more effort to disprove. That’s exactly what we’re doing.”

2022 Grüner Veltliner harvest in Mokelumne River-Lodi’s Mokelumne Glen Vineyards.

Suitability of grapes to climatic regions

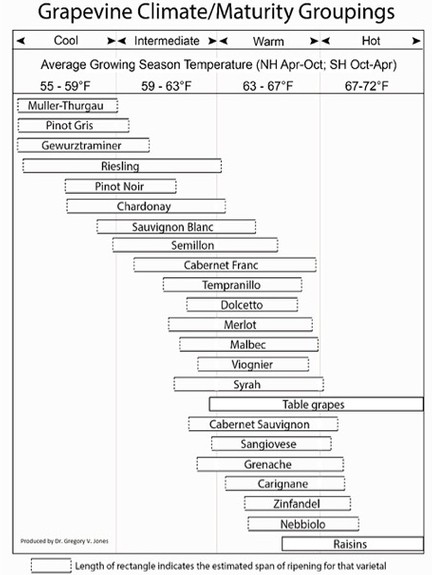

In still another chart, Jones pinpoints optimal climate zones for major wine grapes. Accordingly, “grapevine maturity groupings” are based upon “average growing season temperatures… functionally identical to growing degree-days, but generally easier to calculate and have been related to the potential of varieties to mature in climates worldwide.” The summation:

Professor Jones also illustrates the “Optimum Zone” for grape growing in terms of the impact on grape and, ultimately, wine quality in this graph:

Jones continues: “While many of the cultivars… are grown and produce wines outside of their individual bounds depicted, such examples are usually bulk wines (high-yielding) for the lower-end market, and they do not typically attain the typicity or quality expected for the same cultivars in their ideal climates.”

What makes this pigeonholing of grapes and climate zones somewhat misleading; the conclusions, so torturous? For one thing: the fact that there are numerous vineyards on the West Coast that grow a wide range of cultivars all in one place, and are highly acclaimed for all of them. In France, grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc may be associated with Bordeaux, and Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are associated with Burgundy. California, however, is an example of a place where conventional adherence to recommended “optimum” zones is, more times than not, blithely ignored. Yet in many of these cases, none of this seems to be detrimental to quality, or prestige.

Not only are sensory standards typifying wines of Bordeaux or Burgundy inapplicable to regions outside Bordeaux or Burgundy, they are inapplicable to any perception of terroir, the “sense of place” distinguishing all the finest wines of the world. The finest Bordeaux and Burgundies, you can say, are grown in Bordeaux and Burgundy; the same way the finest Lodi and Napa Valley style wines are grown in Lodi and Napa Valley. As always, consumers are the ultimate arbiters of taste; and more and more of them are appreciating wines for where they come from, not for how they compare with wines from elsewhere.

Close-up of Albariño grown in Southern Oregon’s Abacela estate, which not too long ago produced fat, unctuous, fruit-driven white wines more in the style of warm climate regions, but is now crafted in lighter, crisper styles—having everything to do with winemaking decisions, not a change in climate conditions.

The essence of terroir is that wines can be grown, and greatly appreciated, under widely varied circumstances. Although “climate is the baseline factor,” as Dr. Jones correctly reminds us, it is obviously far from the only factor. How else can wines with characteristics associated with cool climates be produced in warmer climates?

Mr. Niggli concurs, adding this observation: “I am certainly not one to say that any grape can be grown in Lodi. Like Pinot Noir—there is quite of bit of Pinot Noir grown in Lodi, and it doesn’t make the best wine. Still, it is possible to grow many other grapes in Lodi, and they can be quite impressive. Is it because they grow so well in Lodi, or is it because more and more people like the way the wines made from those grapes come out, even though they’re grown in Lodi? Probably both.”

This is not to dismiss the fundamental concept of optimum grape/climate suitability either. It is well known, for instance, that grapes of Mediterranean descent such as Zinfandel, Carignan, and Grenache adapt easiest to warm climates, and far less easily to cooler climates. That is to say, they thrive as plants—hence, the plethora of healthy vines over 50 or even 100 years old in a region like Lodi—and yield fruit retaining enough acidity to give wines freshness and focus, even under the most sun-soaked conditions. It is like saying that Polynesians are best suited to the type of tropical weather in which Scandinavians would more likely be burnt to a crisp. Certain grapes do make sense for Lodi.

Acquiesce’s Sue Tipton, proclaimed 2022’s “Best Woman Winemaker” (in the world, not just California or Lodi) entirely because of the light, subtle, finely delineated sensory attributes of her wines across the board.

Lodi, to hammer home one more final point, has never been known for white wine viticulture. Theoretically, a “warm climate” is not conducive to light, crisp, finely delineated white wines. That theory has been debunked: There is a Lodi-based white wine specialist—Acquiesce Winery & Vineyard‘s Sue Tipton—who was recently proclaimed “Best Woman Winemaker” by the International Women’s Wine Competition (2022). Every year, numerous industry experts and unbiased competitors have been recognizing Acquiesce wines for being among the finest in the world, bar none. By logic, a case could be made for the fact that being grown in a warm climate region is a huge advantage for Acquiese. Thank goodness, when planting her vineyard, Ms. Tipton did not read the reports saying what she should grow, and what she shouldn’t. She simply did the right thing.

Conclusion: Lodi is no different than many other regions of the New World where grapes are successfully grown outside of theoretical “optimal” parameters. Where there is a will—and the genius of the human device—there is always a way, and no amount of opinion or errant assumption seems to stop that from happening.

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorials to The Tasting Panel magazine, crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media, and is the author of the new book “Lodi! A definitive Guide and History of America’s Largest Winegrowing Region.”

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.