MONDAY, JULY 11, 2022. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Featured Image: Visiting wine influencer Lexi Stephens (@lexiswinelist) focusing on the sensory qualities of wine at Bokisch Vineyards.

First principles

It’s funny, no one ever needed an article on “how to taste food,” or “how to listen to music.” We need a few years of school to learn “how to read a book,” but no one needs to be told what their favorite books should be. Appreciation and knowledge of food, music, books, and so many other things—such as cars, clothing, movies, etc.—are pretty much instinctive. There are no lessons to learn, mostly because our lives have informed us of what we really like.

Wine, granted, is a little different. If you like the taste of wine, you’ve reached first base. But to increase your appreciation of wines, especially since there are so darned many of them to choose from, and in so many price ranges, it does help to know a few things about how to taste them.

Wines are deceptive. We can look at them, like we would an armchair, a piece of sushi, or an automobile, and clearly see that they’re white, maybe reddish or pale pink, or sparkling with tiny bubbles. After that, all bets are off. Making delineations in the aroma and taste on the palate demands a little bit of sensory concentration.

One of the most famous instructors of “how to taste wine” was a British Master of Wine named Michael Broadbent. Although there have been other how-to books published, Michael Broadbent’s Wine Tasting (1982) is still an all-time classic. The “bible” by which all the so-called experts swear by.

One of the first principles cited by Broadbent in his book is this: “Practice, Memory, and Notes.” He writes:

Although wine can be consumed with enjoyment without a lot of fuss and nonsense, the reasoned judgment of the finest wines must be based on knowledge, and this can only be acquired by the sort of practice in tasting that will help a vinous memory—a memory that will hold in store the great touchstone, the standard norms and the exceptions to the route.

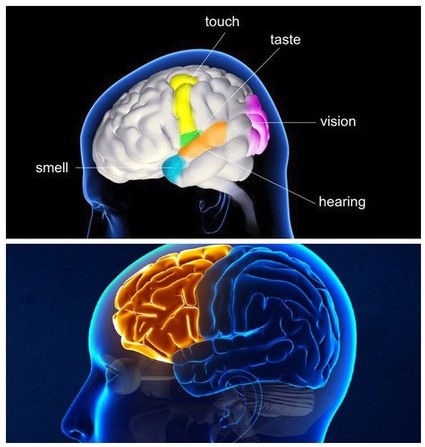

What Broadbent is proposing is that it is true that anyone can enjoy wine, but you can enjoy wine the most when you use your brain—that is, your storehouse of memories—not just your nose and mouth. This past April we devoted a couple of thousand words just on this subject—how your brain functions as your operating system when discerning wines—in our post, Why wine is tasted with your brain, not your palate.

At the top, the temporal lobes of the central nervous system are utilized to distinguish tastes; and at the bottom, the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex are used to process the memories necessary for identifying sensations of smell, touch, taste, vision, and hearing.

Let’s put it this way: If you’re shopping for a new car and haven’t done a lick of research, pretty much all cars look alike to you. You might like this car because it’s a pretty blue color, another car because it looks brawny and has big wheels, or another car because it’s small and practical for squeezing into tight spaces. Beyond that, though, it’s probably smart to have done a little bit of homework on the gas mileage of comparable cars, their mechanical reliability or safety features, airbags, anti-lock brakes, electronic stability control, and adaptive headlights, traction control, and on and on. Stuff that isn’t obvious upon cursory glance.

It’s no different with wines. It helps to do a little bit of reading, or brain exercise. Heck, there are enough stickers on the shelves of an average wine store to help you learn a lot, and wine labels themselves (front and back) can tell you a lot about the differences in wines. What Broadbent suggests, however, is that the best way to learn the taste of wines is to simply remember what you are tasting. This means jotting down a few notes, such as the name of a wine, where it comes from, some basic impressions of its aroma and taste (sweet? dry? tart? smooth? rough? light? heavy?…), and so forth. Unless you have a photographic memory, this is the best way to learn how to distinguish one wine from another.

Put it this way: In his time (1927-2020), Michael Broadbent was considered one of the world’s greatest (if not the greatest) wine tasters. Yet he took notes on every wine he ever tasted. I’ve seen him do it.

Paying attention to the wines you taste, in fact, helps you get the most out of them. Although it certainly isn’t always true—personal taste being such as it is, plus the existence of overrated and underrated products—that the more you spend on a bottle, the better a wine tends to be, if you spend $40, $50 or more on a bottle you might as well get at least $40, $50 worth of wine out of its taste, rather than guzzling a bottle down and promptly forgetting everything about it, the same way you would a $4 or $5 wine. Pay attention to the wines you taste and you’ll get more out of them, which also helps you make better decisions whenever you go shopping.

Widely read wine journalist Elaine Brown (wakawakawinereviews.com) taking detailed notes on every wine in the middle of a Lodi vineyard.

The basic wine tasting steps

Number one, tasting wine is just like tasting food except for the fact that it involves examining liquid in a glass, and getting accustomed to the process which involves

• Seeing

• Swirling

• Smelling

• Sipping

As Yogi Berra might have put it, you can see a lot by looking. It is as important to look at a wine as it is to first look at a dish before you eat it because our sense of smell and taste are most definitely connected to our visual sense. If you see a hamburger, you expect something meaty and drippy, and maybe a little crunchy if there’s a fresh leaf of lettuce and sliced tomato in it. If you see a white wine, you expect something cool and refreshing. Red wines get your senses ready for something dryer and meatier. Sparkling wines typically signal a wine that will be tart, lively with foamy effervescence.

Visiting sommeliers and Lodi winemakers taking notes and carefully tasting white wines at Bokisch Vineyards.

Then you begin the process of tasting, which you start by swirling. Swirling wine in a glass is not an affectation. The reason you swirl is to allow a wine to fall down the sides of a glass which creates the vapors that you smell and perceive as aromas. It is the smell of wine that distinguishes one wine from another, the same way that it is the smell of food that distinguishes one food from another. Without the activation of your sense of smell, all foods, and all wines, taste pretty much the same (ask anyone who has lost their sense of smell for a period of time).

Swirling wines is also why good wine glasses are usually clear and tulip-shaped, with rims that are curved inward plus a stem to help you hold the glass without getting your fingerprints all over the bowl. A curve-shaped glass also helps you swirl the wine without spilling it on your shirt or blouse. The act of swirling works best if you pour a glass only about a third full at a time, thus enhancing the smell of vapors collected beneath the rim. Getting a good wine glass, in fact, is actually step #1—all wines taste better in a good wine glass, and all wines taste worse in a terrible excuse for a wine glass.

At Lodi Crush in Downtown Lodi, the typically pale, brick red color of red wine is made from the Nebbiolo grape.

When smelling, start by holding your glass by the stem and gently twirling it in a circular motion. If this feels awkward, move your glass around in a little circle as it sits on a table.

After that, you smell. As you bring your nose to the rim of the glass, open your mind up to what it reminds you of. You don’t have to, but many wine professionals close their eyes for a second when they focus on aromas, which is what anybody does when they concentrate on the smell or taste of something. It’s a human habit of signaling the brain to do its work, specifically having to do with recalling memories of previous tastes.

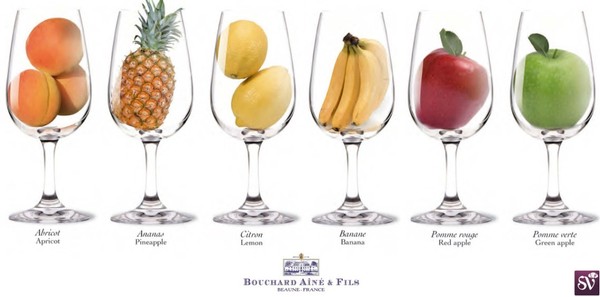

Examples of fruit commonly suggested in the aromas of wines, as suggested in a chart designed by France’s Bouchard Aîné & Fils.

White wines made from the Chardonnay grape, for instance, usually trigger memories of apples, maybe lemon, or even tropical fruit. Red wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon are often reminiscent of dark or red fruits such as blackcurrant and berries, often with a little bit of mint or eucalyptus. Zinfandels often have that blackberry, raspberry, or cherry-like aroma with a touch of “jammy” sweetness in their scent (even if the wine is completely dry on the palate, which it normally is); often with a backdrop of spice (usually suggesting cracked black pepper, although sometimes like cinnamon, clove or other kitchen spices).

While European wines are usually sold by the names of their region of origin, American wines are sold by brand and varietal identification (i.e., the names of the grapes that wines are made from, such as Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Zinfandel, etc.). Paying attention to the smells of fruit suggested in a wine’s “nose” helps you learn the different varietal characteristics; and after you learn that, you can better appreciate the way each brand, and each wine region, interprets “varietal character.”

Finally, after focusing on smells, you actually sip a wine. For wine, this entails the discovery of how the natural elements of alcohol, acidity, and (for red wine) tannin come together with the aromas to create a pleasant (hopefully!) flavor as it sits on the tongue, even before it is swallowed. A good habit is to allow a wine to sit on your tongue for a second or two before you actually swallow it. If you’re at a dinner table, of course, it isn’t necessary to do this with every sip. But it’s a good idea to do this upon your first taste of a wine, which gives your brain a chance to discern sensory impressions.

In respect to a wine’s feel on the palate, alcohol gives a wine its “body,” which is a good word to use when describing whether a wine is light, heavy, or somewhere in-between. White wines from Germany (often made from the Riesling grape) and Italian-style whites made from Moscato tend to be less than 10% alcohol and thus are among the lightest wines in the world, and very easy to drink. California and French white wines made from Chardonnay tend to fall in the 13%, and 14% alcohol range, and thus are usually described as full-bodied or even heavy. Most varietal whites made from Sauvignon blanc tend to be lighter, around 12% or 13% alcohol, and so are usually medium-bodied—neither light nor heavy. Even beginners can quickly learn what their personal preference may be in terms of varietal and body, and that’s the important thing.

Red wines such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Zinfandel, Syrah, and Petite Sirah usually have full alcohol (13%, 14%, or more) as well as generous levels of tannin—the latter component, derived from the skins and seeds of grapes with which red wines are fermented—which further accentuate the feel of the body. Although red wines made from grapes such as Pinot noir, Grenache or Cinsaut can be just as high in alcohol as Cabernet Sauvignon or Zinfandel, they may very well taste lighter or softer in the body simply because they are typically lower in tannin, which adds to the dryer and sometimes bitter sensory impressions. Therefore, if you prefer red wines that are softer or more “delicate” you may be more of a Pinot noir or Grenache lover; but if you love a full-bodied red wine with more tannin grip, you may be more of a “Cabernet” person.

Finally, you make a quality assessment. You need not be a Master of Wine to make a valid judgment on quality. As in anything—music, books, fashion, cars—everyone needs to decide what is best for themselves. You must be your own judge of quality.

That is, did you enjoy the look, the aroma, and the taste of a wine, or was it just so-so to you? If you do not like dry, bitter-tasting red wines, you may prefer lighter, sweeter, fruiter white wines, which means these are the best wines for you. Rosés have become very popular because they tend to be dry, but are always crisper, lighter, and fresher in aromatic fruit qualities than red wines. If you prefer a white wine that is bone dry or a red wine that is soft and spicy, then these are the wines you should be seeking out to enjoy. The important thing, going back to our first principles, is that you need to remember your preferences; and when you remember, you can explore further possibilities in the styles of wine you enjoy.

If you have a democratic, or catholic, taste (in the sense of appreciating any type or style of wine, as long as it is well crafted), then the qualities you usually end up looking for in a wine usually entail a sense of balance, a harmonious feel, smoothness or “finesse” of different elements in wine, whether it is dry, sweet, light or full-bodied, white or red, pink or bubbly.

One of the advantages of cultivating a democratic taste, I should add, is that it allows you to better appreciate wines with foods. It is true, no matter what anyone may say, that certain wines go better with certain foods, and vice-versa. A Cabernet Sauvignon, for instance, is immensely satisfying with a grilled steak, Zinfandel is amazing with barbecued ribs, and Albariño is totally refreshing with ceviche, raw oysters, or seafood salads in a citrusy vinaigrette. If you can appreciate all kinds of wines, you can probably better enjoy wines in their optimal food contexts. And if you take the word of people in Europe who (after all) invented wine, wine is food—or at the very least, something that is best enjoyed with food as sustenance in and of itself.

Half the joy of learning how to better appreciate wines is becoming more capable of finding other wines that are equally enjoyable, especially with the foods you love to eat.

All the words you need to talk about wine

Entire books and magazines, of course, are devoted to the description of wines, which can be quite involved and complicated. In any everyday setting, however, all you really need are six basic wine terms, which can help you communicate the taste of wine to yourself, as well as to anyone in polite conversation. The basic terminology:

Color or appearance: Is a wine still or sparkling… pink, a pale or golden white, or red as in a deep purplish ruby or a lighter, brick-toned burgundy?

Aroma: A wine’s smell, which transitions into “flavor” once it hits the palate… what does a wine remind you of—a certain fruit, a spice, a flower, or even a mineral or sense of earthiness? This, more than anything, is what Broadbent meant when he coined the phrase “vinous memory,” which is what you use when distinguishing wines. Every wine’s soul, or sense of place in the world, is in its aromas.

Popular wine influencer Elle Rodriguez (@themodernpour) with Turley Wine Cellars barrels and bottles of Sandlands Wines, parked at Lodi’s Kirschenmann Vineyard.

Dryness/sweetness: Does the wine have some degree of sweetness, or none at all (a wine with no perceptible sweetness is considered “dry”)?

Body: A wine’s weight on the palate (is it light, full, or just “medium” in body)?

Acidity: Level of tartness, especially in whites and sparklers, and to a lesser degree in reds… is a wine zesty or tart, or the opposite, soft and round?

Tannin: A component pertinent to red wines since tannin comes from skins and seeds (red wines are fermented with skins and seeds, whereas white wines are fermented after the pulp is separated from skins)—is a red wine big or hard in tannin, or is it light, soft, or just moderate in its tannin?

Being able to talk about wine helps you to distinguish one from the other. Once you are able to do this, you are on your way to becoming a “Master” of your own universe of wine appreciation, which is all that really matters!

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine, crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media, and is the author of the new book “Lodi! A definitive Guide and History of America’s Largest Winegrowing Region.”

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.