MONDAY, JULY 12, 2021. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

The era of saloons and gamblers

In 1874 the 450 or so citizens of a little town called Mokelumne — nestled in the lush watershed area of California’s Mokelumne River, just east of the marshy Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta — decided they needed a name change. So they came up with “Lodi.”

A short and sweet, pronounceable name probably wasn’t the only thing that was needed. At that time, the community was being drawn up in unpaved roads, bogged down by sticky mud during the winter rains, and engulfed in nostril-clinging dust when stirred up by the Delta breezes during the desert-dry summer months. One local historian has called late 1800s Lodi “an unruly child… sometimes referred to as a ‘rum-guzzling’ town with young boys on the road to hell” (Christman, Our Time to Shine).

Above, Lodi’s original Southern Pacific Railroad Depot around 1869; and below, a recent shot of the Lodi Transit Station.

In his Historical Study of the Public Schools of Lodi, California, Ralph Morton Wetmore recounts an 1886 incident taking place in the Salem District schoolhouse (at the time located just north of East Lodi Avenue and east of South Stockton Street) illustrating the times:

The school was often used as a community meeting place. One of the groups using the building was a well-known lodge of the time known as The Independent Order of Good Templars. It is reported that one evening while the Order was in session some unprincipled character entered the anteroom and emptied the entire contents of a whiskey bottle into the drinking water bucket. It was not long in being discovered and soon there was a waiting line at the water bucket. All was well until a conscientious sister discovered the reason for the sudden thirst. An uproar followed and the incident came near disrupting the lodge.

As with most rural American towns, “respectability” for Lodi came in baby steps. Some of the community leaders strongly felt that incorporating into a City would help. A motion in 1904, however, was decisively voted down, primarily due to the opposition of saloon owners and other businesses. But on November 27, 1906, an election was held by the Lodi citizenry (population 2,000 at that time), and the proposal was passed by a 2-to-1 margin. What turned the tide, writes Lucy Reller and Ralph Lea in Lodi Historical Society‘s Lodi Historian newsletter, was “the opposition of the saloon keepers had a reverse effect and increased the desire of church people and the average citizen to incorporate.”

On December 3, 1906, the San Joaquin County Board of Supervisors decreed that Lodi was duly incorporated as a municipality, which became official three days later upon filing with the California Secretary of State’s Office. Finally, writes Christman, Lodi’s “citizens were well on their way to respectability.”

The more “respectable” saloon in the grandly scaled Hotel Lodi, opened in 1915, a period of time when local temperance groups were successfully resisting the expansion of more saloons in and around the City of Lodi. Lodi Historical Society.

But those civilizing elements did not happen overnight. Writes Christman, on the 1880s and 1890s:

… Lodi was considered wild, uncontrolled, and causing great distress to peaceful residents. Partiers patronized too many saloons spending too much money gambling on cards, or horse, dog, and turkey races. Then for lack of anything else, they threw their hard-earned dollars away on turtle races!

Inhabitants carried sports to extremes as a diversion from everyday life. On Sundays, and Holidays, especially July 4th, the business world would close its doors and shopping came to a standstill. Sacramento Street would come alive with bystanders, bettors, and spectators lined up taking pleasure in observing the horses and dog races. Well-attended baseball games against nearby towns provided additional Sunday wagering opportunities in both money and prizes. These wagering events were sometimes followed by a dance at the Sacramento Street Park…

Early 1900s photo of Woodbridge Lodge No. 131 of Free and Accepted Masons, one of the many civic-minded orders active in the Lodi area in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Lodi News-Sentinel.

Authorities attempted to curb illegal gambling practices in Lodi. The Club Saloon in 1902 had the nickel-in-the-slot machine, only to meet its fatal fate. The three slot machines [one-armed bandits] in Lodi Hotel in 1903 were given a fond goodbye with their faces turned facing the wall. In the refined Chinatown community, the income needed to pay debts was instead being lost on lottery tickets.

Then there were animals — not wild ones, just a pungent domestic population. Writes Reller and Lea, it wasn’t until 1895 that the County Board finally appointed a “Poundmaster” to “pick up dogs, pigs, horses and cattle, etc. from the streets of Lodi during the day, but at night most people opened their gates to allow animals to eat grass and Lodi looked like a country fair.”

From the 1890s, photo of 16-horse wheat harvester at the 640-acre Spenker Ranch, complete with the horse driver perched on a Joseph’s Ladder. Wanda Woock’s Jessie’s Grove.

Agricultural identity

This classic, rugged Western town, however, was quickly becoming renowned as an agricultural community, by virtue of its phenomenal natural resources: mild winters, bright summers, extremely rich and deep sandy loam soil, and an abundance of water from both an aquifer just below the surface and from what could be diverted from the Mokelumne River fed by snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada, less than a day’s horse ride away to the east.

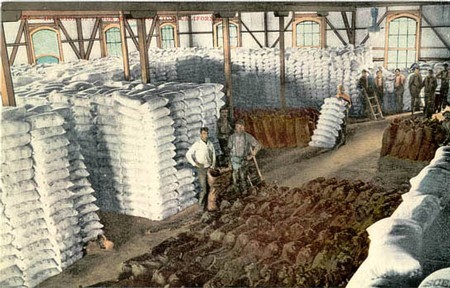

Colorized version of an 1876 photo of the Lodi Flouring Mill, which reported produced up to 200 barrels of flour a day at the height of Lodi’s wheat production days. Lodi Historical Society.

In 1876, reportedly the world’s largest crop of wheat (3.4 million bushels) was raised in the areas immediately surrounding Lodi. When wheat and barley prices failed, local farmers turned to watermelons, and by the early 1890s Lodi had a new title as “Watermelon Capital of the Country.” And when the watermelon market began to fade, local growers turned to a crop that didn’t need to be reseeded each year: grapes for both wine (the big buyer was El Pinal Winery in nearby Stockton) and fresh consumption.

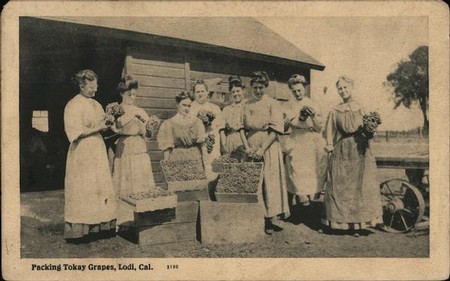

Insofar as table grapes, by 1905 Lodi became associated primarily with Flame Tokay, a European Vitis vinifera eminently suited to the region’s rich soils and dry Mediterranean climate marked by diurnal temperature swings. By 1907 Lodi’s enterprising fruit packers were shipping over $10 million — over $240 million by today’s currency — in grapes for the fresh market, although Flame Tokay could also be turned into wine, primarily for brandy distillation.

1880s photo of a Lodi “watermelon cabin,” during the brief time Lodi was known as the “Watermelon Capital of the Country”.

Families of German descent

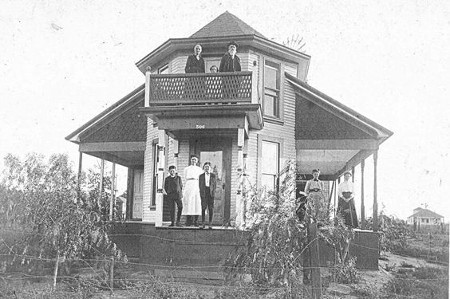

Most of Lodi’s flush of new arrivals between the 1890s and 1920s were families of German descent. This rapidly growing segment of the population (by 1925, swelling to over 6,000) came for the land and agricultural opportunities, but what they found in their new home may have been less than acceptable from a social standpoint.

Adds Christman about this period of time: “Race tracks plus about 14 saloons far outnumbered its four Churches. Abstemious Germans were appalled by main street lined with bars sporting brass railings, spittoons, scantily dressed fast ladies of the night, loud piano music, and mugs of beer for five cents. Worse, those establishments were open all evening, including, heaven forbid, Sunday! Because there were too few churches for the population, religious services were often held in saloons.”

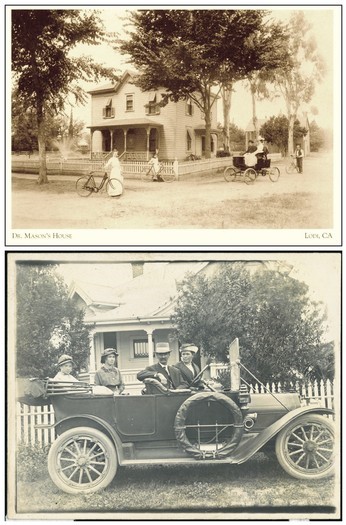

Rapid progress: In 1900, Dr. Wilton Mason proudly shows off his horseless carriage (Lodi’s first ever) with his family in front of their home at North School and West Elm Streets; in the second photo from 1911, Henry and Jessie Beckmen (daughter of Joseph Spenker) with their daughters Vera and Anita in their new EMF Studebaker. Lodi Historical Society and Wanda Woock’s Jessie’s Grove

Hence, in December 1906, when Lodi’s newly appointed Board of Trustees began to meet to establish order, new laws, and revenue sources, ordinances were passed to curb things like saloon licenses, gambling, swill disposal, horse and livestock enclosures, speed limits for the growing number of horseless carriages (8 miles per hour!), and control of neverending medicine shows.

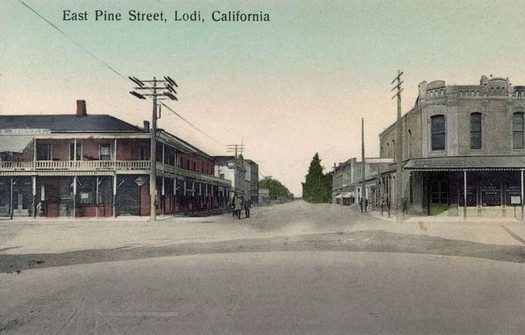

Even more importantly, Lodi’s incorporation as a City and ability to levy and collect taxes would almost immediately lead to the establishment or improvements of essential services such as utilities, especially for gas, electricity and water, waste and sewage disposal, fire hydrants and protection, and street paving. The first Lodi streets to be paved would be School and Pine in 1912.

The Lodi Ladies step up

“Progress and betterment of Lodi” was also the stated goal of the Lodi Ladies Improvement Club, established in 1906 by 28 women determined to play a stronger role in civic improvement than had previously been possible through their various church groups, local temperance and anti-saloon movements, or through female chapters paralleling men’s organizations such as the Masonic Lodge, Knights of Pythias and Odd Fellows.

Even before Lodi became a City, it was Lodi’s “pioneer ladies” (as the Lodi Historian describes them) who successfully raised the funds to found the Lodi Public Library and Free Reading Room. They initiated this drive in 1885, which culminated in the opening of the Lodi Carnegie Library in 1910, with the help of a $9,000 grant from the Carnegie Foundation.

Two enduring achievements of the Woman’s Club of Lodi née Lodi Ladies Improvement Club: the Lodi Carnegie Library (dedicated in 1910) and the Woman’s Club of Lodi (completed in 1923).

Among the other early projects driven by the Lodi Ladies Improvement Club were upgrades in schools, fire protection, streets and sidewalks, garbage collection, trees, and overall beautification of the rapidly growing City. In 1913, when membership had grown to 65, the civic-minded group’s name was changed to the Woman’s Club of Lodi, and soon after, a Woman’s Building Association Inc. was established, selling 10,000 shares at $5 apiece.

A lot on E. Pine Street at Lee Avenue was purchased for $10 in gold, and by 1923, at 450 strong (with each member pitching in another $5 in dues), the ladies were able to open the doors of their own meeting place. This ornately columned, neoclassical-style auditorium — at that time, the largest hall of its type in Lodi — is still used by the organization today (enshrined in 1988 as No. 88000555 on the National Register of Historic Places).

During Lodi’s first decade of the 1900s, the influx of a more pious populace led to the establishment of no less than a dozen new churches of various denominations. “This rough ‘n ready settlement,” writes Christman, was steadily transformed into “a God-fearing town.”

1912 photo of Victor School, which opened in 1911 with 96 students to accommodate the rapidly growing population of settlers on the east side of Lodi, most of them of German descent, and many of them closely related. Lodi Historical Society.

Thou shalt not date thy neighbor

There were catches, however, to this newfound godliness. Adds Christman, “By WWII, when Lodi’s population was approximately 8,000, nearly half were of German descent. The joke among these folks was: knock on any Lodi door and a relative will answer. In later years, the joke became: if you want to date someone, find out first if you are related!” To this day, in fact, vintners from longtime Lodi farming families on both sides of the City will tell you exactly that — always date, or marry, someone from outside of Lodi, lest you end up hooking up with a relative.

Finally, in a burst of civic pride, in 1907 the burgeoning City’s rank and file mobilized to announce its presence to the rest of the entire world by organizing the Tokay Carnival. This three-day, knockdown celebration of the region’s supreme grape product and Lodi’s attendant economic arrival was memorialized by the Mission-style Lodi Arch that still stands at Pine and Sacramento Streets (since 1980 as National Register of Historic Places property No. 80000848).

No matter how you slice it, the fact that the name “Lodi” is now seen on store shelves of virtually every retail outlet in the U.S., plus most of the rest of the world where American wine is sold, is quite an achievement. Without a doubt, little did the conscientious sisters of The Independent Order of Good Templars know that this would ever happen, way back in 1886.

Colorized postcard of Lodi’s Sacramento and Pine Streets in 1887, from a photo taken from where the Lodi Arch would be erected 20 years later, with the original Lodi Hotel on the left.

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine and crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.