The Lodi Winegrape Commission and the University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources (UC ANR) are partnering to provide Lodi winegrowers with the latest information about grape pest management. This is the first of several excerpts from the third edition of the Grape Pest Management book to be published here in the Coffee Shop.

In Grape Pest Management, more than 70 research scientists, cooperative extension advisors and specialists, growers, and pest control advisors have consolidated the latest scientific studies and research into one handy reference. The result is a comprehensive, easy-to-read pest management tool.

The new edition, the first to be published in over a decade, includes several new invasive species that are now major grape pests. It also reflects an improved understanding among researchers and growers about the biology of pests. With nine expansive chapters, helpful, colorful photos throughout, here’s more of what you’ll find:

- Diagnostic techniques for identifying vineyard problems

- Detailed descriptions of more than a dozen diseases

- Comprehensive, illustrated listings of insect and mite pests,including the recently emerging glassy winged sharpshooter and Virginia creeper leaf-hopper

- Regional calendars of events for viticultural management

- Up-to-date strategies for vegetation management

__________________________________________________________________________________

Click HERE to purchase your copy of Grape Pest Management.

__________________________________________________________________________________

This excerpt from Grape Pest Management (Third Edition) was published with permission from UC ANR, and was written by Larry Bettiga, Paul Verdegaal, and Matthew Fidelibus.

__________________________________________________________________________________

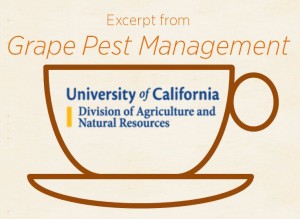

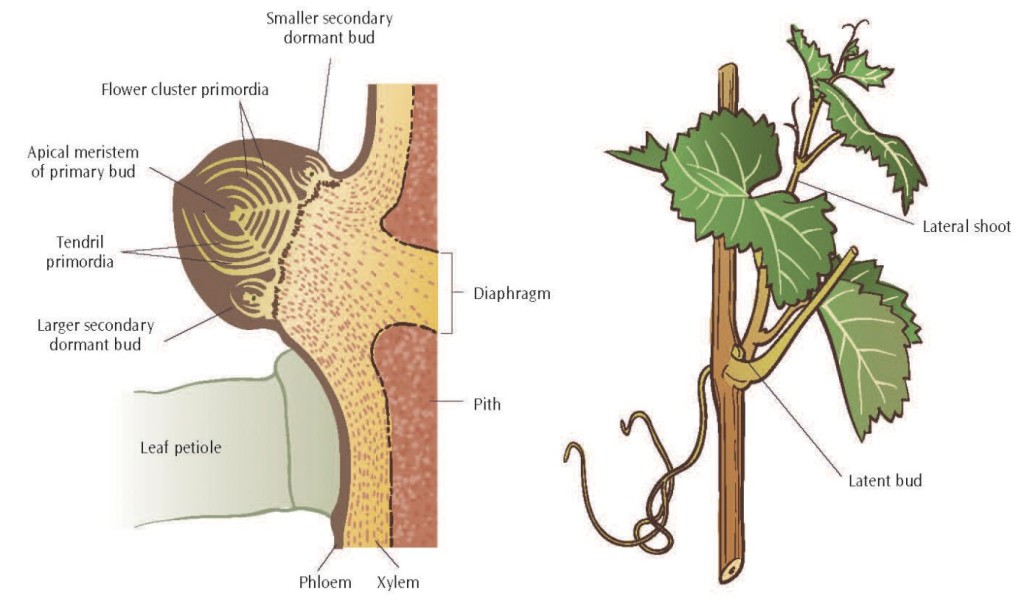

Shoots

The succulent new growths that extend from each bud are called shoots. By fall, mature, woody shoots that dropped their leaves and entered dormancy are called canes. The length of grapevine shoots and canes is partitioned, alternately, into nodes and internodes (fig. 2.1).

Nodes are the thickened sections that have buds from which new shoots may arise. Internodes are the smaller-diameter sections between each node. Each cluster is borne opposite a leaf on nodes near the base of a shoot. Tendrils, which replace clusters on more apical nodes, occur in an alternating pattern so that a tendril is formed opposite each of two adjacent leaves but not formed opposite the third leaf. This pattern is observed for all grapevines except Vitis labrusca, which has tendrils on most nodes.

Cells that compose new leaves, clusters, tendrils, and other tissues are formed by division of the apical meristem at the tip of each actively growing shoot. Newly formed cells then differentiate and expand, so that young leaves and other organs appear to unfold from the shoot tip. The shoot growth rate depends on environmental conditions. Unlike many deciduous plants, grapevine shoots do not form terminal buds. Shoot growth will continue if there is sufficient heat and an abundance of moisture in the soil.

Buds

As shoots develop, two types of buds are formed at each node in the leaf axil at the base of the petiole. Lateral, or prompt, buds are formed first. Prompt buds are so named because lateral shoots arise from them in the season the buds are formed; these shoots are also referred to as summer laterals. Lateral shoots may be very short or quite long. Most of the short lateral shoots fail to lignify and drop from canes during dormancy.

Figure 2.2: At left, a cross-section of a dormant grape bud attached to a cane, with internal features ad the position of leaf petiole attachment. At right, a shoot showing a lateral shoot that has grown from the leaf axil and a latent bud.

Regardless of its length or persistence, each lateral shoot will form a latent bud in its first leaf axil; this leaf is reduced to a prophyll, a bract or scalelike structure. This latent bud may also be referred to as a compound bud or an eye. Latent buds generally contain three growing points, each with partially developed shoots, including rudimentary leaves, tendrils, and flower clusters. A compound bud generally remains dormant after it has formed until the following spring. Then, in most instances, only the middle, or primary, growing point will emerge (fig. 2.2). Death or injury to the primary bud or some environmental conditions can result in the growing of secondary or tertiary buds, or both. Secondary and tertiary buds are generally less fruitful than the primary bud.

Leaf

Figure 2.3: Sap balls, or pearls, are a natural exudate and may be found on the underside of grape leves in spring; they are not be be confused with insect or mite eggs. Photo: J. K. Clark.

The grape leaf consists of a blade (or lamina), the petiole, and a pair of stipules at the base of the petiole (see fig. 2.1). Full expansion of the mature leaf blade occurs 30 to 40 days after it unfolds from the shoot tip. The upper surface contains very few stomata; it may have epicuticular hairs, and it has a well- differentiated layer of epicuticular wax consisting of overlapping platelets. The lower surface lacks a wax layer but can contain epidermal hairs of various types (woolly, glandular, thorny), depending on the cultivar. The lower surface has many stomata arranged in a random nature. There are approximately 170 stomata per mm2 (110,000 per in2). The leaf blade has five main veins that arise from the petiole at the same point.

In spring under conditions of high temperature and humidity, grape leaves and shoots can produce natural exudates that form sap balls on the underside of leaves, on petioles, and on shoots; these balls can be confused with insect or mite eggs (fig. 2.3).

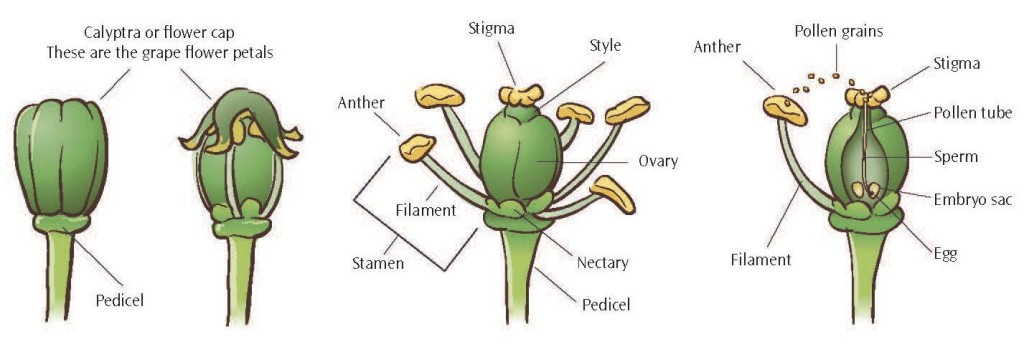

Flowers and Fruit

Grapevines have small flowers, typically 4 to 5 mm (0.17 to 0.20 in) long, that are grouped together in a cluster, or inflorescence. Before bloom the calyptra, a cap of fused petals, encloses the other flower parts. Each calyptra detaches from its base at bloom, exposing pollen-bearing stamens and a pistil with the ovary, the enlarged basal portion ( fig. 2.4). If pollinated, the ovary of each flower may grow and develop into a berry.

Figure 2.4: Stages of grape flower bloom. (1) Grape flower not yet in bloom with cap attached. (2) Flower in early bloom with cap dehiscing. (3) Flower in complete bloom showing ovary and stamens. (4) Pollinator and fertilization of a grape flower.

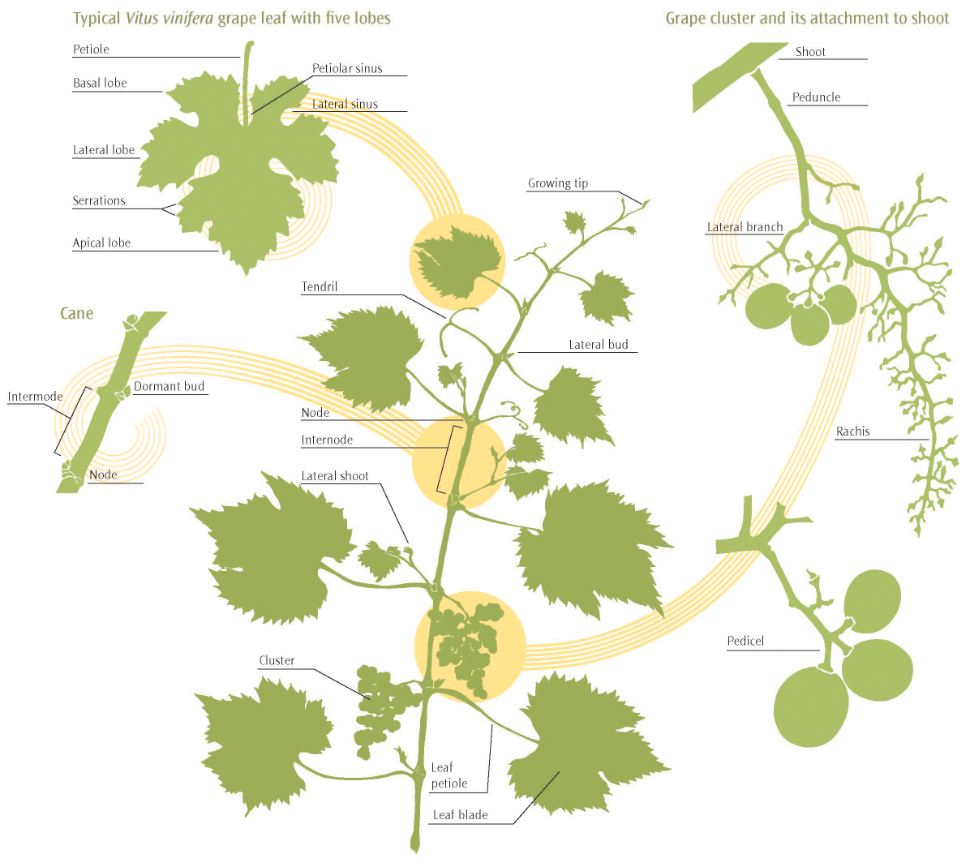

Each cluster is attached to a shoot by a peduncle; the entire length of the main cluster stem framework is referred to as the rachis, with individual berries being attached to the rachis by a pedicel, sometimes referred to as a cap stem (see fig. 2.1). Clusters vary widely in shape and size, depending on the grapevine variety and by the position of the cluster on the shoot. Common cluster shapes are shown in figure 2.5. The classification depends on the number and length of the lateral branches of the cluster stem. Clusters with several well-developed laterals near the peduncle are called shouldered. When the first lateral developing from the peduncle is large and separate from the cluster, it is referred to as a wing.

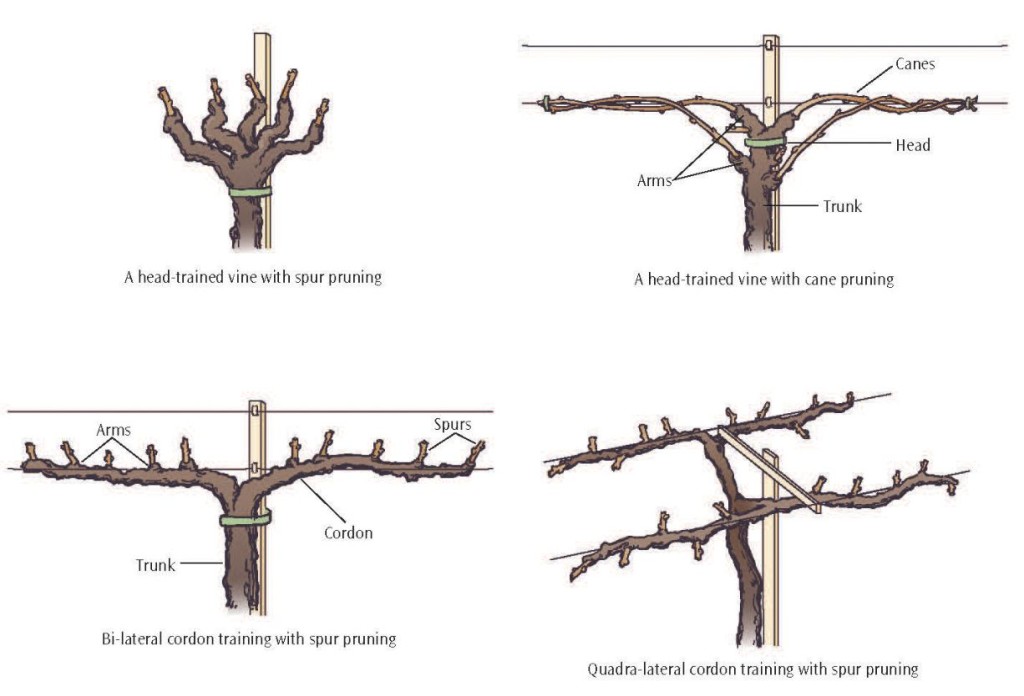

Grapevine Structure

Cultivated grapevines are trained into various forms with the aid of a trellis system that helps support the permanent vine structures, the annual canopy, and the fruit.

The main aboveground structures are the trunk, head, cordons, arms, spurs, and canes. The trunk branches into arms or cordons, depending on the training system. From these arise fruiting wood, 1-year-old dormant wood. This wood may be retained each year as spurs, canes, or both, depending on the grapevine variety and on the cultural practices the vines may be subjected to. Spurs are short fruiting units, 1 to 4 nodes long, with 2 node spurs being the most common. Canes are longer fruiting units that are typically 8 to 15 nodes long. The four main training and pruning systems are shown in figure 2.6.