APRIL 17, 2018. BY STAN GRANT.

First: A Bit About Grapevine Buds

Grapevines are hardy plants that have several traits to help them survive. Compound buds are among these. Elongating shoots trained to form grapevine trunks, arms on head-trained vines, and cordons on cordon-trained vines all develop compound buds at nodes located at intervals along their lengths. Compound buds consist of a prompt bud (a.k.a. a lateral bud) and a latent bud, which itself is composed of a primary, secondary, and tertiary bud under the same set of bud scales (Figure 1). The lateral bud may give rise to a lateral shoot during the current season, but the latent bud remains dormant. Although latent buds may remain dormant indefinitely, they have the potential to produce shoots any time circumstances are favorable. While dormant, latent buds remain functional at a low level and continue to very slowly elongate so adjacent woody tissues do not overgrow them.

What are Water Sprouts and Suckers?

Water sprouts and suckers are undesirable shoots arising from latent buds. Water sprouts are shoots originating on above-ground wood and suckers originate on below-ground wood. Correspondingly, water sprouts arise mainly from the scion and suckers arise from the rootstock. Many in California call all shoots arising from latent buds “suckers” and some call removal of water sprouts from cordons and arms “crown suckering” or simply “suckering”. Here, we will stick with the internationally accepted terms of water sprouts and suckers. Certain varieties appear more prone to produce suckers and water sprouts than others. Those with low growth vigor are commonly among them (e.g. the Pinot varieties) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Water sprouts are common near the bottom of Pinot gris trunks. (Progressive Viticulture©).

Issues with Water Sprouts and Suckers

Water sprouts and suckers are undesirable for several reasons. They are viticulturally inefficient, siphoning off resources, including water and nutrients, better used to support desirable growth and fruit production (Figure 3). In addition, suckers and water sprouts on trunks limit herbicide options. On cordons and arms, water sprouts intensify shading within canopies (Figure 4). In so doing, they decrease fruit exposure to air and sunlight, thereby diminishing fruit quality, increasing the potential for disease, and reducing the effectiveness of foliar sprays.

Figure 3: Rootstock suckers divert internal vine resources away from useful root and shoot growth. (Progressive Viticulture©).

Water sprout and sucker removal during winter, while vines are dormant, create wounds that serve as entry points for airborne and soilborne pathogens. Even in-season sucker and water sprout removal have some fungal disease risk, although typically for a shorter period of time and involving less virulent wood pathogens than dormant removal. If suckers and water sprouts are left intact or partially removed, latent buds proliferate on subsequent growth, and water sprout/sucker problems compound.

Managing Water Sprouts and Suckers

Cost-effective control of water sprouts and suckers requires a multipronged strategy. The first prong is limiting the number of latent buds. To begin, acquire vines for a new or replant vineyard from a reputable nursery with a sound rootstock disbudding process and inspect the vines for the presence of rootstock buds and suckers before accepting delivery. After planting, irrigate and fertilize to promote moderate vine growth, targeting about 4-inch-long internodes (Figure 1). Such a growth rate limits the number of nodes and latent buds compared to slower growth.

Figure 4: Water sprouts create excessive shading of leaves and clusters within canopies. (Progressive Viticulture©).

Promoting apical dominance is the second prong of water sprout and suckers control. Apical dominance is a phenomenon in which organs positioned higher on vines suppress the activities of organs positioned lower on vines.

For our purposes, we aim to use buds on bearing units (spurs or canes) and the shoots arising from them to suppress latent buds lower on the vine. To this end, train trunks as tall as practical and as rapidly as possible, followed by prompt establishment of cordons with numbers of spurs proportional to the growth vigor of the vines. For horizontally divided trellises, ensure that the non-bearing (blank) cordon sections extending between trunks and cordon wires are lower than the cordon wires. After vines are established, avoid severe pruning that concentrates resources from roots into too few count buds, thereby lessening the capacity of bearing units to suppress water sprouts and suckers.

The last prong of water sprout and sucker control is prompt removal, especially while establishing a vineyard and during its early years. Remove rootstock suckers shortly after they appear, cutting them below their bases to remove the whorl of latent buds immediately above. Similarly, remove water sprouts early (Figure 2), either rubbing them off while they are less than a few inches long or cutting below their bases when longer. Cordon water sprout removal also provides an opportunity for improving the spacing, uniformity, exposure, and growth of the remaining shoots, as well as reducing pruning costs and entry points for canker disease during the winter.

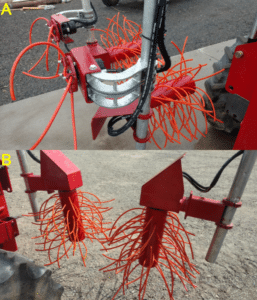

Mechanical sucker and water sprout removal equipment is available (Figure 5), but it is less precise than careful hand removal. Certain chemicals can also control suckers (e.g. paraquat), but they usually work best when applied while suckers are short.

Figure 5: Machinery designed to remove water sprouts on cordons (A) and trunks (B). (Photographs courtesy of VineTech Equipment, used with permission).

To Summarize

Suckers and water sprouts divert vine resources away from useful growth and fruit production, and thereby, decrease viticultural efficiency. Their control requires high-quality nursery stock, prompt vine establishment, and a vineyard design that enhances the dominance of shoots arising from buds on spurs or canes. It also requires careful and consistent pruning, and prompt sucker and water sprout removal early each growing season, especially while vineyards are young.

Further Reading

Galet, P. General Viticulture. Oneoplurimedia, Chateau de Chaintre, France, 2000.

Jackson, D. Monographs in Cool Climate Viticulture-1. Pruning and training. Canterbury, NZ, Lincoln University Press. 1998.

Makatini, GJ. The role of sucker wounds as portals for grapevine trunk pathogen infections. M.S. Thesis. University of Stellenbosch. 2014.

Tassie, E; Freeman, BE. Pruning. pp. 66-84. In B. G. Coombe and P. R. Dry (Ed.). Viticulture Volume 2 Practices. Winetitles, Adelaide, 1992.

Winkler, AJ; Cook, JA; Kliewer, WM; Lider, LA. General Viticulture. Univ Calif Press, Berkeley, 1974.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe” or click on “join our email list” to the right.

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

To join the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Community as a grower or a vintner, email stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “LODI RULES.”