MONDAY, APRIL 11, 2022. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Featured Image: Lodi’s Somers Vineyard — old vine Mission planted right alongside the winding Mokelumne River.

One of the most interesting things to happen in the Lodi appellation just over the past three, four years is the sudden popularity of an 18-acre vineyard called Somers. Ten years ago the owners of Somers Vineyard couldn’t give their fruit away because it produces a translucent, light red wine (barely 12% ABV) with a low fruit profile and absolutely no tannin backbone. Before that, the only people interested were grape concentrate producers.

Yet the Somers Vineyard is a beautiful site, located right along a bend of the Mokelumne River. The plants themselves, with roots dipping into the water table, are tall, rather majestic, vertical cordon trained vines with tree-like trunks, planted some 50 years ago. The problem was, that the vineyard is planted with Mission vines, a grape variety from which the California wine industry has been trying to run away for over 170 years.

Lately, however, at least half-a-dozen small, artisanal style wineries have been standing in line to buy Somers Vineyard Mission. Ironically, it is because the grape makes translucent, light red wines with a low fruit profile and absolutely no tannin backbone — exactly, or so it seems, what a growing number of today’s consumers are looking for.

Is this interest in light, bony red wines indicative of a pervasive market trend? Undoubtedly not. If anything, it is indicative of a growing preference among a tiny minority of consumers. Not everything is a sign of the “next big thing.”

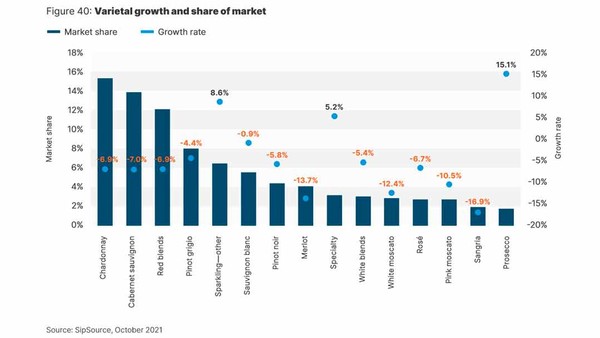

For example, the vast majority of today’s white wine lovers prefer a fairly dry and fuller-bodied wine. Yet a good, strong percentage of consumers still prefer a white wine that is decidedly sweet and light (i.e., alcohol levels as low as 5% to 7%). Varietals such as Muscat, or Moscato, currently hold down slightly less than 3% of the American wine market — not nearly as much as varieties producing dry whites such as Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, or Pinot Gris/Grigio (see The US wine industry in 2021 did well or great). Point is, though, there will always be a small minority of wine drinkers who prefer sweet, fruity wines, no matter what the predominant trend may be.

Insofar as red wines, of course, the big sellers are made from grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot noir, Zinfandel, Petite Sirah, and the endless variations of blends that can be made from these varieties. Most red wine drinkers in the U.S. obviously love their wines dark, rich, and as full-bodied and aromatic as possible. Mission makes an opposite style of red wine.

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Amador County in 1848, the only wine grape growing in California (as well as in Mexico and New Mexico) was Mission — a cultivar belonging to Vitis vinifera (i.e., the classic European family of wine grapes), also known as Criolla or Pais, originally brought over from Europe by Spanish missionaries to produce their sacramental wines.

By the late 1850s, however, the new slew of enterprising growers and vintners in The Golden State (California statehood came quickly after the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, in 1850) were aggressively bringing in dozens of other wine grapes from nurseries on the East Coast. Zinfandel, in particular, quickly came into favor because it took to California’s Mediterranean climate like fish in water. It also produced a darker, richer flavored wine that could ripen much more quickly than Mission. A no-brainer.

Somers Vineyard manager Mike Anagnos with one of the larger Mission specimens in this riverside growth.

The University of California/Sotheby’s Book of California Wine (1984) makes note of the declining opinion of the Mission grape during the mid-nineteenth century

It is well suited to the hot climate of southern California, it yields heavy crops, it makes quite good sweet wines, and it will no doubt continue to be grown in California for many years… After all, this has been said, one must add that the Mission is not a distinguished grape, especially for table wine: it is low in acid and lacks distinctive varietal flavor. Even without direct evidence, we are fairly safe in concluding that the dry table wines, both red and white, made by the mission fathers were, at best, rather flat and dull.

Mission, however, never really disappeared. In 1984 the USDA California Field Office reported that there were still over 3,000 acres of the grape planted in the state. Latest reports show 404 acres, although there are many old vine plantings throughout the state, including Lodi, where smatterings of the grapevine can still be clearly identified, especially among blocks planted mostly to Zinfandel. There are a few, albeit tiny, blocks in Amador County dating back to the 1850s and 1860s devoted entirely to Mission. It’s a grape that refuses to “die.”

Lodi-grown Mission reds

There is absolutely no doubt that much of the newfound popularity of table reds made from Mission has been coming from consumers who may, indeed, appreciate darker, richer red wines, but who don’t want to drink these wines all the time. They are often in the mood for something lighter in color and weight, and with more subtle fragrances.

As much maligned as it is, there is, in fact, a varietal profile common to many Mission bottlings. It is floral (like rose petal) rather than deeply fruited, and there is often a good amount of kitchen spice (peppercorn, allspice, and occasionally touches of turmeric, cumin, or green notes suggesting coriander) in the nose. The low-key fruit notes can suggest cranberry, cherry, or pomegranate. The tannin level of Mission is almost negligible, which is also a good thing for a lot of people who tire of drinking strictly “heavy” reds. Even the tannin level of most Pinot noirs, a variety known for soft tannin, is consistently higher than that of a typical Mission.

The variety is also known for its lack of acidity. Lodi’s Somers Vineyard, however, is a special case: Because this vineyard grows a big crop of large clustered fruit, it can be even slower to ripen than most Mission plantings. In most years, in fact, Sommers Vineyard fruit tends to ripen unevenly — meaning, it is often picked when some clusters are sweet with nearly raisined berries, while other clusters are still tart, almost green in flavor.

Therefore, many vintners drawing from Somers Vineyard are picking their fruit when they are, technically, partially underripe, which results in natural acids that are still fairly high. Moreover, when sugar levels are slightly low, this results in wines fairly low in alcohol (between 12% and 13% ABV). Therefore, a typical Somers Vineyard Mission does, in fact, have a mildly zesty acid edge to it, along with the light and easy feel appealing to more and more consumers.

Wineries that currently produce varietal Mission reds from Somers Vineyard include Pax Wines, Sabelli-Frisch, Voluptuary + Lucid Wines, Toogood Estate Winery, Found Wine Co., Ramos-Torres Winery, Nue Wilde, and Vending Machine Wines.

Our notes on three recent bottlings:

2019 Monte Rio Cellars, Lodi Mission ($24) — Pale brickish red with an effusive, if irresistible, fruit fragrance suggesting red berries, cranberry, and a whiff of curry plant-like herbiness, although it is on the palate where the wine distinguishes itself: a fresh, markedly light, easy drinkability wrought by mildly perky acidity and pillowy soft tannin lending focus to the clarity or purity (i.e. sans oak) of the red fruit quality, finishing with a touch of dusty earth tones. If you’re fond of, say, Beaujolais from France, you’ll like this wine, although it has less of the tutti-fruitiness of typical Beaujolais, and more of the herbal/earthy/dustiness typifying many a Lodi grown red (particularly old vine Zinfandel when made with zero oak influence, which characterizes this wine).

2019 Sabelli-Frisch, “La Malinche” Somers Vineyard Mokelumne River (Lodi) Mission ($29) — Owner/winemaker Adam Sabelli-Frisch unabashedly dubs his their “signature” wine, citing Mission grape’s history as California’s “oldest… mistreated and neglected for over a century” — which is exactly why he is attracted to the grape. The wine is flowery with nuances of cherry/berry and maple syrup. On the palate, it is soft and light with a mild zestiness; its tannin so negligible that the wine comes across as almost pillowy/feathery in its delicacy, ending with an easy, palate-freshening quality.

2020 Lucid L.03 “Urban Flora” Rosé ($28) — This iteration of Somers Vineyard-grown Mission is more of a bright, orangy brick-tinged rosé, enhanced by a touch of Lodi-grown Viognier. It is made by fermenting on the skins for five days, then pressed off to finish fermentation in neutral oak barrels. The result is, unlike a typical rosé, this wine retains a mild tannin level that contributes to a feel closer to that of red wine (albeit, a very light and soft red wine). The nose abounds in rose petal, red berry, and kitchen spice (cardamom, nutmeg, mace) aromas typical of the grape, which are manifested in a light yet intense, zesty, vividly flavorful qualities on the palate. There is also an umami-like savoriness to the wine’s lip-smacking middle and finish.

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine, crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media, and is the author of the new book “Lodi! A definitive Guide and History of America’s Largest Winegrowing Region.”

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.