MONDAY, MAY 3, 2021. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

My old employer, Julio Gallo used to say, “the best care a vineyard receives is the footsteps of its owner.” In other words, the most important element of vineyard care is vineyard monitoring (Figure 1). As such, vineyard monitoring is critical to vineyard business success.

Figure 1. Vineyard monitoring is a component of successful vineyard management. (Photo Source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Key vineyard observations at particular seasonal grapevine developmental stages guide management decisions, especially those regarding the scheduling and intensity of resource applications. Hence, vineyard monitoring affects return on input investment.

Vineyard observations also provide early detection of pests, diseases, deficiencies, disorders, and stresses, allowing time management intervention to minimize costly vine damage and losses in fruit production. For this reason, vineyard monitoring is essential to managing viticultural risk.

Monitoring must be sufficiently thorough to render a reliable impression of vineyard condition, but given the many demands on vineyard managers, monitoring must also be efficient. This article discusses some techniques and technologies for systematic vineyard monitoring that promote accuracy and efficiency.

Remote Vineyard Monitoring

Several technologies allow efficient vineyard monitoring from the vineyard office and other remote locations. Perhaps, the most important of these, monitor the vineyard environment. For example, weather stations can provide information about disease pressure (e.g. powdery mildew), insect pest development (e.g. vine mealybug), and vineyard water use (evapotranspiration or ET) (Figure 2). Soil moisture sensors follow changes in soil moisture status that can aid irrigation scheduling. Monitoring irrigation system operation and energy consumption remotely are also possible.

Figure 2. Monitoring atmospheric conditions and soil moisture within a vineyard using a weather station. (Photo Source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Remote sensing of vineyards from the air is another labor-saving technology when regularly scheduled, high-quality aerial images are involved. Such images depict variability and changes in vineyards over the course of a growing season. They also portray improvements in vineyard uniformity and condition due to applied inputs.

Although environmental monitoring and remote sensing technologies greatly increase monitoring efficiency, sensor number and/or capability limit the scope of their observations. Consequently, they are supplements rather than substitutes for visual observations. As in Julio Gallo’s day, boots on the ground and eyes on the vines remain central to effective vineyard monitoring.

Systematic In-Field Vineyard Monitoring – Where

Different vineyard management concerns require different levels of monitoring. Some problems, such as certain pests and irrigation system leaks, can randomly occur anywhere. Therefore, they require periodic transects across the entire vineyard. For such work, vineyard managers frequently benefit from the assistance of aerial images and reliable support staff.

Other management issues tend to be zonal, being associated with differences in soil, slope, or aspect within a vineyard. These differences are visibly manifest as variations in vine size, rate of shoot growth, internode length, leaf size, the extent of canopy development, and occurrence of stresses. Zones may be identified during vineyard transects, from aerial images, or from some other vantage point.

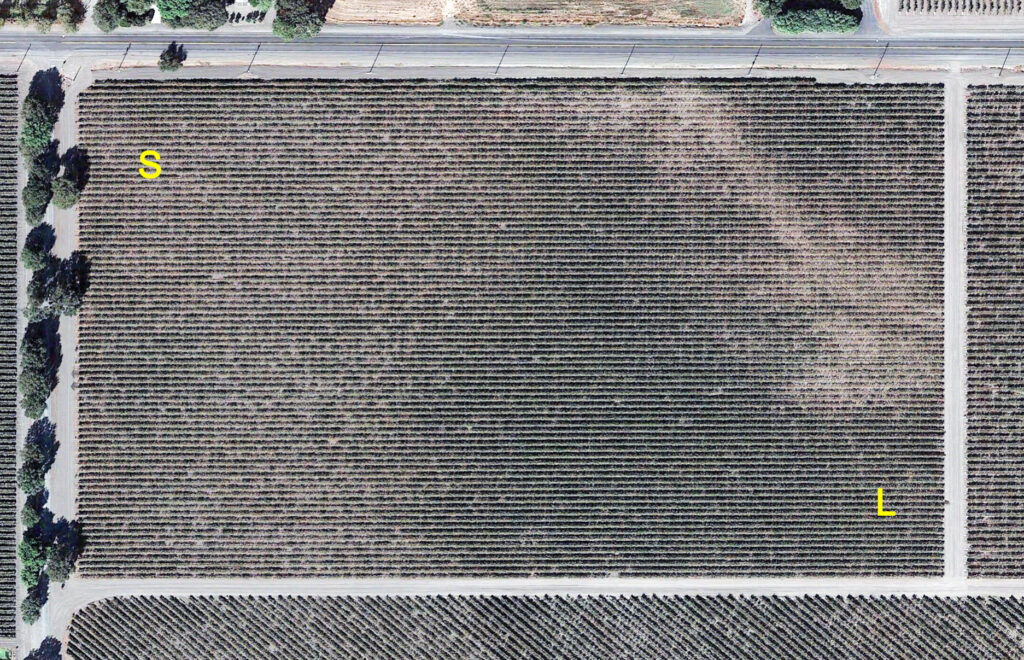

Within each zone, select two representative adjacent rows to serve as a monitoring station (Figure 3). In season, use these stations to monitor the growth and development of canopies and crops, as well as the onset of vine maladies. Exclude vines near the ends of the rows from your observations because they are usually not representative of a majority of vines within the zone. The consistent use of well-chosen monitoring stations within a zone greatly enhances the precision and usefulness of vineyard observations over time.

Figure 3. There are two monitoring stations within this vineyard; one (S) for the smaller vines in the west and another (L) for the larger vines in the east. (Note the band of restricted vine growth across the northeast requiring additional attention). (Base Aerial Image Source: Google Earth, 2018)

Systematic In-Field Vineyard Monitoring – When

To be effective, maintain a schedule of regular vineyard visits. The frequency of the visits, however, can vary with the time of year. During the winter, while vines are dormant, visits can be less frequent. Pests present on the vineyard floors, like weeds and gophers, are the primary focus of wintertime monitoring, but cane condition and soil moisture are also important.

After shoots leaf out, increase the frequency of vineyard visits. At least one visit per week is required to capture rapidly changing vineyard conditions during the growing season. Also, broaden the scope of your observations according to the stage of seasonal grapevine development, recent and forecasted weather, and lifecycles of pests and diseases.

Systematic In-Field Vineyard Monitoring – How

Develop and routinely use a sequence of observations. A top-down approach is an example, in which you first focus on the condition of the canopy and then the clusters, the cordons and trunks, drip irrigation lines, vineyard floors in the vine row, and vineyard floors in the tractor rows. While making visual observations, pay attention to details and expect the unexpected.

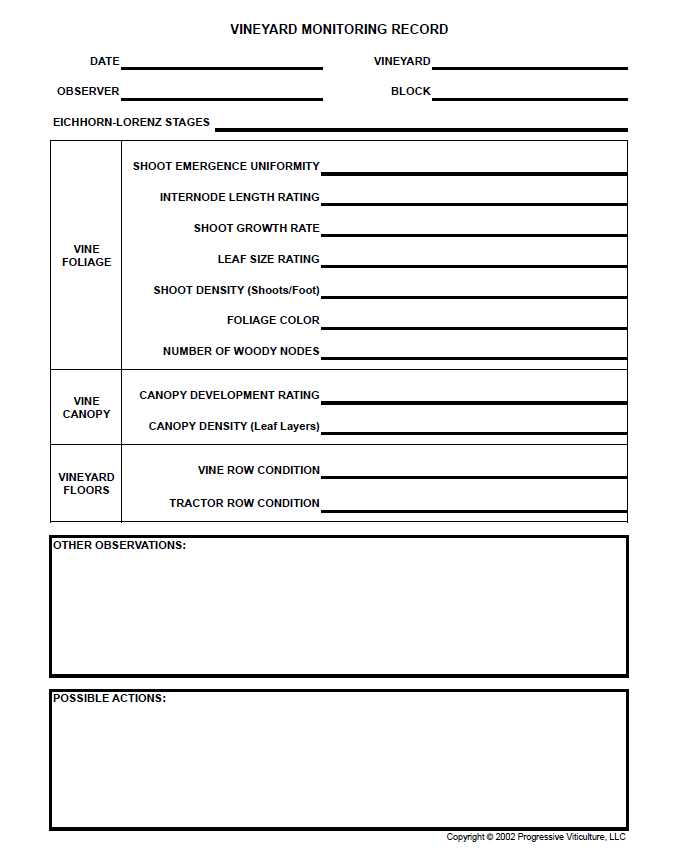

Note the Eichhorn-Lorenz stage of seasonal grapevine development at each vineyard visit. In this system, the stages of development involve (in seasonal time sequence) buds, number of leaves, clusters, flowers, berries, cane wood, and leaf fall (Table 1). Other noteworthy vineyard observations include internode length rating, shoot growth rate, prevailing leaf size, foliage color, shoot density (shoots per foot cordon or cane), degree of canopy development (number of nodes or leaves per shoot), canopy density (number of fruit zone leaf layers), and the extent of cane ripening.

Do not rely on your memory. Rather, record your important observations, using a notebook, form page, or tablet database (Figure 4). Apps are available to allow you to record geo-referenced observations, sometimes with dropped pins on maps, attached notes, or attached photos. Monitoring records are indispensable management references of dates of specific vine development stages, as well as the timing, locations, severity, and reoccurrence of vineyard problems.

Figure 4. An example of a record sheet for systematic viticultural monitoring of a winegrape vineyard. (Source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Knowing where to look greatly increases the efficiency of monitoring for potential problems. For example, leafhoppers prefer lusher, more vigorous growing vines, which are common on the ends of vine rows. Mites, on the other hand, prefer dusty, stressed vines often found near roadways. A trail of ants on a trunk and cordon usually indicate a mealybug infestation, which their presence under bark confirms. Powdery mildew infects young berry tissues, while Botrytis infects mainly old berry tissues. Phosphorus and magnesium deficiency symptoms develop on leaves near shoot bases, boron deficiency symptoms appear on mid-shoot leaves, iron deficiency symptoms develop near shoot apices, and nitrogen deficiency symptoms usually appear across entire canopies.

Comprehensive vineyard monitoring also includes periodic sampling and analysis of soils, irrigation waters, and grapevine tissues for mineral nutrient status. Again for consistency, collect soil and vine tissue samples from preselected vineyard monitoring stations. For more information about sampling, please refer to the Lodi Winegrowers Workbook.

Some low-tech tools can aid vineyard monitoring. A shovel, which is necessary for checking grapevine roots and soil moisture, is paramount among them. A hand lens is helpful for clearly seeing insects and fungal growths. Use a pocketknife to check the condition of questionable vascular tissues on stems, canes, cordons, and trunks. Although not low-tech, a cell phone or tablet with a camera and texting capacity is handy for communicating what you have seen in your vineyard.

In Summary

Vineyard monitoring is an essential part of successful vineyard management. To be effective and efficient, monitoring must be systematic. Technologies that enhance monitoring efficiency can be part of the system, but effectiveness ultimately depends on in-person vineyard observations. Effective in-field monitoring, in turn, relies on knowing where, when, and how to make observations at various times during the growing season. Consistency in the location and timing of vineyard visits, method of observation, and keeping of records is the final component of systematic vineyard monitoring.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services May 2005 newsletter and was updated for this blog post.

Further Reading

Bettiga, LJ (ed.). Grape pest management. 3rd Ed. University of California Agricultural and Natural Resources, Oakland, CA. Publication 3343. pp.120-125. 2013.

Coombe, BG. Phenology. In Viticulture volume 1: practices. Coombe BG; Dry, PR (ed.). Winetitles, Adelaide. pp.139-153.1988.

Goffinet, MC, Pratt, C. Grapevine structure and growth stages. In Wilcox, WF; Gubler, WD; Uyemoto, JK (ed.). Compendium of Grape Diseases. 2nd (ed.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN. pp. 5-15. 2015.

Grant, S. Risk management for vineyard businesses. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (lodigrowers.com). November 16, 2020.

Grant, S. Five-step irrigation schedule: promoting fruit quality and vine health. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 21(1): 46-52 and 75. May/June 2000.

Grant, S. Soil moisture monitoring. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (lodigrowers.com). April 8, 2014.

Grant, S. Regulated deficit irrigation, parts I and II. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (lodigrowers.com, lodigrowers.com). July 18 and August 4, 2014.

Grant, S. Remote sensing and aerial images in vineyard management. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (lodigrowers.com). March 30, 2020.

Ohmart, CP, Storm, CP, Matthiasson, SK (ed.). Lodi Winegrower’s Workbook, 2nd (ed.). Lodi Winegrape Commission. 2008.

Smart, R, Robinson, M. Sunlight into wine: A Handbook for Winegrape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1991.

Wilcox, WF, Gubler, WD, Uyemoto, JK (ed.). Compendium of Grape Diseases. 2nd (ed.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN. pp. 33-39. 2015.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.