SEPTEMBER 24, 2018. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

In recent years projects like Lodi Native – where groups of Lodi winemakers have been producing single-vineyard Zinfandels following the exact same, native yeast/neutral oak protocols (thus eliminating brand or winemaker styles as factors) – have been proving something that old-time growers and vintners have known all along: that there are differences among Lodi Zinfandel plantings – often subtle, but sometimes drastic – grown in different parts of the Lodi AVA.

The Lodi Native project has endeavored to demonstrate the distinctions in terms of sensory qualities manifested in the wines. But each year, the differences are actually demonstrable in comparisons of clusters and berries from each vineyard.

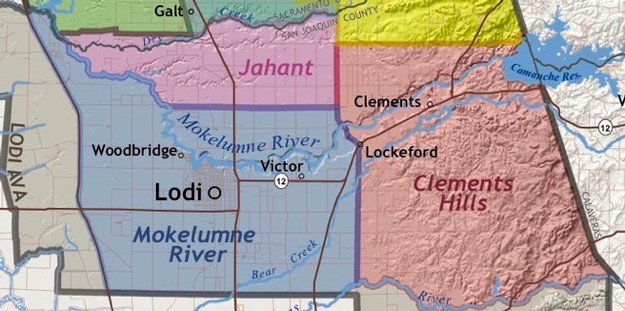

Over 99% of Lodi’s Zinfandel plantings are concentrated in the sub-appellation of Mokelumne River, centered around the City of Lodi. There are also a few older, old vine plantings in Lodi’s Clements Hills AVA; all located alongside the winding Mokelumne River near the little hamlets of Lockeford, Clements and Dogtown, east of the City. The common terroir-related factors of all these vineyards:

♦ Sandy loam soils, primarily in the Tokay Series

♦ A steady, warm Mediterranean climate consistent throughout the AVA; from the flat, 50-ft. elevation areas on the far west side to the low lying slopes (150 to 400-ft. at the highest) on the far east side.

The differences that you find in both the physical manifestations of vines, clusters and berries as well as the sensory qualities of resulting wines result mostly from the slight variations in vineyard topographies. In some sites – particularly in the east side of Lodi (roughly, the areas falling east of California Hwy. 99) – the soil is sandier and deeper. For instance, there one particularly large swath of ground centered around the little CDP of Victor (on Victor Rd./Hwy. 29 East between Lodi and Lockeford), that is more of a loamy sand than sandy loam; an observation confirmed as far back as the 1937 USDA Soil Survey of The Lodi Area, California (Cosby & Carpenter).

Most of vineyards west of Hwy. 99 consist of the classic Tokay Series soil – also deep (30 to 50 feet of consistent sandy loam, devoid of rocks, gravel or hard pans), porous, but quite rich in organic material of alluvial original (basically, finely crushed granite washed down from the Sierra Nevada over the past 100,000 years).

So how big of an impact are the “east vs. west” side factors on Zinfandel plantings? Take a look at a comparison of average size clusters from four vineyards that have been bottled as Lodi Native Zinfandels over the past four years:

While berry sizes in all but the Stampede Vineyard sample are proportionate, the biggest difference is in the size and weights of clusters as a whole: the west side vineyards producing Zinfandel bunches as much as double the size as east side vineyards. Berry size is smallest in the Stampede Vineyard because it is located in a more stressful riverside site in the Clements Hills, where the soils are more depleted and even more of an ultra-fine, powdery sandy loam. The result of slightly elevated skin-to-juice ratios in Stampede are Zinfandels with consistently firmer acid/tannin structure than average Lodi Zinfandels (which, as a whole, tend to be on the softer side).

All the vineyards depicted in this comparison are own-rooted (i.e. ungrafted). While vine age is always one more differentiating factor when it comes to Zinfandel viticulture and wine quality, the vineyards used in this comparison are of a comparably advanced age:

- Lot 13 Vineyard – over 90% of block surviving from original planting in 1915

- Stampede Vineyard – field mix planted between the 1920s and 1940s

- TruLux Vineyard– field mix with oldest vines planted in the mid-1940s

- Soucie Vineyard – oldest block planted in 1916

2018 Zinfandel harvest in Lot 13 Vineyard on Lodi’s east side

McCay Cellars owner/grower/winemaker Michael McCay farms and produces Zinfandel from Lot 13 Vineyard, and has been producing Zinfandel from TruLux (farmed by Keith Watts) for over 15 years. According to Mr. McCay: “The Zinfandel clusters in TruLux are always larger, more elongated, with small berries – almost Cabernet-ish, whereas Lot 13’s are a smaller, tighter clusters, with few if any wings. Interestingly, you can take clusters from both TruLux and Lot 13 that are similar in size, but the west side cluster from TruLux will always be heavier in weight.

“A big reason is the soil. The sandy loam is heavier and a little loamier on the west side, with a little more water holding capacity. East side vineyards in general are sandier; but especially in Lot 13, with its immediate proximity to the Mokelumne River, and hundreds of thousands of years that this site had to build up its layers of silty, sandy soil. The sandy loam in TruLux is a much further distance from the river.”

102-year-old own-rooted Zinfandel in Soucie Vineyard on Lodi’s far west side

“More important is the difference in style of wine that you get. Between TruLux and Lot 13, it couldn’t get any more different. Lot 13 is typical of the east side, where you get a more aromatic style – a more intensely perfumed, bright red berry fruit, with zestier qualities in the mouth. TruLux Zinfandels are a bigger, richer style, with a fuller feel in the mouth, and earthy flavors that you never find in Lot 13. These are direct byproducts of the differences in soil, which you can see in the vines and clusters.”

Over the past 20 years, one of the selections of Zinfandel that has come into favor among Lodi growers is Primitivo – a clonal variant that typically produces bunches with a looser, longer cluster architecture than older Zinfandel selections; proving less prone to rot, mildew and other disease pressures common to grape varieties in which berries are packed together more tightly.

Here is a visual of the differences between a typical Zinfandel cluster and typical Primitivo cluster; both from vineyards located on the west side of Mokelumne River-Lodi

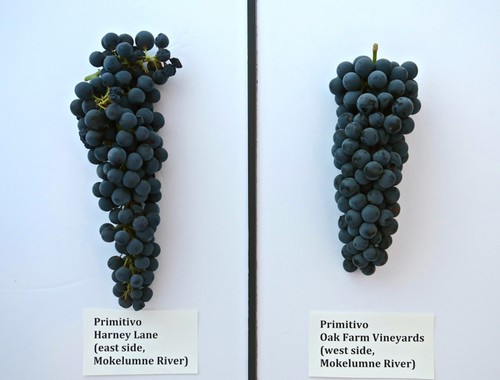

But even with single-clone selections like Primitivo, site can also be factor in both cluster morphology and wine quality. Here is a comparison of clusters from two recent, trellised plantings of Primitivo; one from Harney Lane Winery’s east side Lodi estate (planted in 2000), and the other from the west side Lodi estate of Oak Farm Vineyards (planted in 2012):

Chad Joseph, the consulting winemaker for both Harney Lane Winery and Oak Farm Vineyards, has been working with both Primitivo plantings since their inception. Says Mr. Joseph: “Although each year is different, both vineyards are showing their east side/west side characteristics. There is more variation in berry size in the Harney Lane this year, and a little more shot berry (i.e. tiny green beads between berries resulting from erratic fruit set during the spring), giving the clusters a looser morphology. In recent vintages, I’ve found the Oak Farm Primitivo clusters to be a little more elongated than Harney Lane’s. This year, Oak Farm’s berry size is a little more uniform than Harney Lane’s; but that consistency seems to be typical of vines on the west side, with its richer soils.

“When it comes to the wine, what the two Primitivo vineyards have in common is the bright red fruit – the fleshy raspberry quality as well as a bright acidity, like a pluot freshness – which is typical of wines made from Primitivo, though similar to what you find in Zinfandel picked during earlier ripening stages.

“The differences between the two vineyards are nuanced, but notable. In the Oak Farm, it’s that west side earthiness – a mushroomy loaminess – as well as a fleshier raspberry jam. The Harney Lane Primitivo is a little more perfumed and focused; with an emphasis on the pure, floral aspects of the grape, as opposed to the heavier jam fruit and maybe slightly sweeter finish that you can get in the Oak Farm.”

2018 Primitivo on trellised vines in Oak Farm Vineyards

While variations of soil and topography are what is making contemporary artisanal style Lodi grown Zinfandel more and more interesting, there is still one more factor that is less understood, but nonetheless impactful; and that is concerning Zinfandel selections.

Like all the major varieties of Vitis vinifera – be it Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot noir, Sauvignon blanc, Tempranillo, Riesling, or Sangiovese, et al. – Zinfandel is known to have variants, or clonal mutations; and in an especially large region like Lodi (by far the most widely planted in the U.S., especially when it comes to Zinfandel), growers have always been aware of those existing variants, even if the process of selecting material for planting hass been less than scientific.

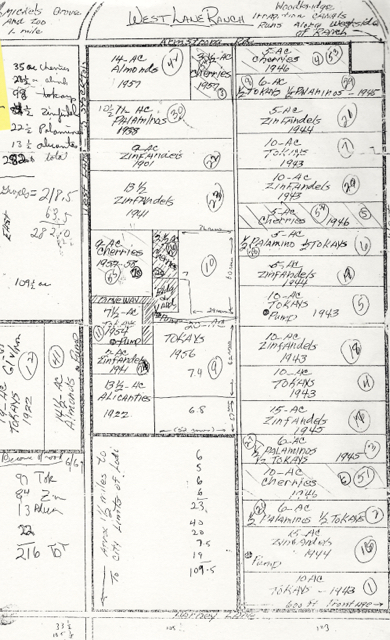

How could it be, when all of Lodi’s “old vine” plantings took place between the late 1880s and early 1960s, long before institutions like U.C. Davis began to conduct formal studies of Zinfandel selections (such as the Zinfandel Advocates & Producers funded Zinfandel Heritage Project, which began in 1995)?

Instead, when planting new blocks or inter-planting old blocks with new material, Lodi growers historically sought out wood taken from either their own vineyards or from neighboring vineyards that were known to produce a consistent, dependable fruit product; especially prior to the 1940s, when much of Lodi’s Zinfandel was packed into small crates and shipped towards the East Coast for home winemakers.

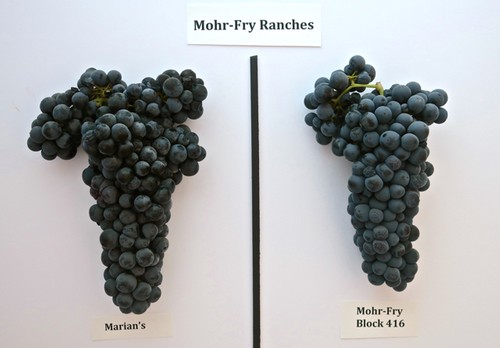

A perfect example of this is Mohr-Fry Ranches – located south of the City of Lodi on the west side of Hwy. 99 – where there are no less than 8 different blocks of Zinfandel, all own-rooted; the oldest being the venerated Marian’s Vineyard (planted in 1901), and the rest, identified simply by block numbers, planted during the early 1940s.

Here is a visual demonstrating an average Zinfandel cluster from Marian’s Vineyard compared to one from Mohr-Fry Ranches Block 416, planted in 1944:

Since, typical of all the Mohr-Fry Zinfandel blocks, these clusters come from plantings just a few feet away from each other – and therefore planted on pretty much a consistent soil type – much of the differences in cluster morphology is attributed to wood selection. Says vineyard manager Bruce Fry: “Because the youngest Zinfandel blocks were planted 20 years before we took over the ranch (in 1965) from the Mettlers, we have no idea of where the plant material came from – that’s a mystery. What we know is that Marian’s produces a longer, larger cluster, and always with bigger berries. Block 416 produces consistently smaller, shorter clusters, with smaller berries. Is it the selection? The site? That’s the mystique of it all, I guess.”

Bruce’s father, Mohr-Fry CEO/President Jerry Fry, comments: “I am guessing that the biggest difference is the source, or wood, used when Marian’s and Block 416 was planted. There is, however, a slight difference in soils. There is a little more sandy loam all the way through in Marian’s Vineyard, and a little more lime lenses in the subsoil of Block 416.

1965 map of Mohr-Fry Ranches (top-side, facing south; bottom, facing City of Lodi) given to the Fry family from the Mettlers; which shows the 1901 Marian’s Zinfandel Vineyard (middle, third block from top) sandwiched between a 1938 Palomino and 1941 Zinfandel block, along with Tokay and Alicante Bouschet blocks dating back as far as 1922. Block 416, planted in 1944, is the second block from the bottom-right.

“In the past, when addressing issues like grape bunches drying up from the bottom, we’ve done soil analyses and sent augers into the ground to get a better idea of what we have underneath. In various parts of the vineyard we hit upon some thin layers of limestone; in some spots, it was like hitting concrete. And so while the entire ranch is fairly uniform in its loose, sandy loam, we’ve always known that the growth in some of blocks is definitely affected by these soil variations.

“Otherwise, all the blocks are treated pretty much the same, and all are grown on their rootstocks, with sub-surface irrigation. Theoretically, there should not be a lot of differences, but there are, and for not a lot of reasons except, as Bruce mentioned, the selection of different plant material over the years.”

In Mohr-Fry Ranches: Jerry and Bruce Fry with St. Amant’s Stuart Spencer

St. Amant Winery has been producing Zinfandel from both Marian’s Vineyard and Mohr-Fry Block 416 since the 1990s. According to St. Amant winemaker/owner Stuart Spencer: “I am not sure how the lime lenses affect fruit quality and composition, but I’m sure it plays a part in the vineyard’s signature. There are more vigorous and weak spots throughout the vineyard. In the weak spots vines clearly produce a lot less fruit, have more exposure (due to less leaf canopy), which ultimately affects vineyard expression in the wines.

“Marian’s Vineyard is the anomaly among the eight blocks in Mohr-Fry’s home ranch, and not just because it is the oldest. It would appear to be a different clone or selection with more elongated clusters and slightly larger berries on average. Yields typically average around 3 tons/acre, but this year it came in a little over 4 tons/acre (picked just this past week, mid-September 2018). Which is pretty remarkable for a 117-year-old vineyard. The particular block typically shows a bit more concentration and tends to have more spice elements mixed with a blend of red and dark fruits.

Mohr-Fry Ranches’ Block 416 in early September 2018

“We’ve been making wine from Block 416 since 1996 (bottled as St. Amant “Mohr-Fry Ranch”), which to me represents a classic Lodi Old Vine Zinfandel. There are bright red and dark fruits. It tends to have more up-front fruit than Marian’s, with an underlying brambly, tea leaf quality. Block 416’s yields average slightly higher than Marian’s, in the 4-5 ton/acre range; although this year, we’ve seen as little as 1 ton/acre. In really low-yielding years, a slight heat spike near harvest can send sugars high quickly resulting a bigger more intense style of Zinfandel, highlighted by rich dark fruits and less of the underlying brambly quality.”

One of the blocks between Block 416 and Marian’s is Mohr-Fry Ranches’ Block 417, planted in 1945. Oak Farm Vineyards has recently bottled a Block 417 vineyard-designate wines. Winemaker Chad Joseph tells us: “The clusters from Block 417 are a little more compact and rounded than what you find in Marian’s; typically with little wings. I find consistently lighter, perfumed, almost delicate qualities in Zinfandels from this block. It may seem less concentrated, or have less dark fruit qualities than other Lodi Zinfandels; yet they are very elegant, nuanced styles of Zinfandel – often with beautiful raspberry/cherry fruit expressed in these light, smooth styles, with just hints of the earthy qualities you get in west side sandy loam vineyards.”

Mike McCay in TruLux Vineyard on Lodi’s west side

Finally, Mitch Cosentino – former owner/winemaker of his eponymous Cosentino Winery – has had an even longer history working with Mohr-Fry’s Block 417. Recently over the phone, Mr. Cosentino told us: “I’ve always preferred this particular block for its slightly larger sized berries than the other blocks’. I find that bigger berries give more juicy, jammy ‘stuff’ than smaller berries. These always seem to be the Zinfandels with the purest black cherry fruit component; always in balance, never flat, and well structured.

“Are there differences in Mohr-Fry Zinfandels, between the 1901 and 1940s blocks? Put it this way – in tasting Zinfandels, or Primitivos, in Italy and Croatia, where the grapes are supposed to have come from, I have never found a resemblance between the wines from there and wines in California. My personal opinion is that what you find in vineyards in California are mutations of what originally came from Croatia more than 150 years ago.

“So I’m not surprised to find that the different blocks in Mohr-Fry, evidently planted at different times and maybe for different purposes, exhibit different cluster and berry sizes, even though the blocks are just a few feet away from each other. I used to work with another vineyard not far away, on Scottsdale Rd., which was an inter-planting of vines going back to the early 1900s with vines planted some 50 years later, and you could clearly see the differences in vine, cluster and berry sizes, not to mention taste. Just one more thing that makes Zinfandel a lot more interesting a wine than what many people think!”

Certified Historic Vineyard marker in Mohr-Fry Ranches’ Marian’s Vineyard

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.