MONDAY, MARCH 8, 2021. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

What’s In a (Varietal) Name?

The term varietal, as the long-departed wine scribe Robert Lawrence Balzer wrote way back in 1948 in his book California’s Best Wines, is actually “an early California idea.” Balzer defined it, simply, as the way of “naming wines after the grape species used in their making,” as opposed to the use of “generic titles… such as Claret, Burgundy, Sauternes, Hock, Moselle, etc.” that were much more prevalent in Balzer’s early days (Balzer authored 11 wine books and syndicated wine columns published in newspapers like Los Angeles Times all the way up to the early 1980s).

There are two questions we’d like to address in this post:

1. When did varietal wines become identified as the finest wines made in America?

2. Are varietal wines, in fact, the finest wines grown and produced in the U.S., or has their time passed?

So let’s go back in history to find the answers: A long, long time ago — oh, shortly after dinosaurs were left off of Noah’s Ark, and a man could make a living selling shoes or delivering milk and still have more than enough to marry, buy a house and raise half-a-dozen kids — Americans “discovered” the alcoholic beverage made from grapes called wine, which Europeans purportedly drank every day, like water.

But it took a long time before Americans appreciated wine in a way remotely similar to Europeans. At least, that is, since the days of Prohibition, which ended in 1933. But much earlier, in the late 1800s, a very large percentage of Americans were, essentially, Europeans, who had just landed off of boats from the old country to the New World. Despite a dearth of domestic product, USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) statistics from between 1875 and 1900 show a modest per capita wine consumption rate of .45 to .55 gallons (re Thomas Phinney’s A History of Wine in America, page 374). By 1935, according to the California Wine Institute, wine consumption had sunk to .36 gallons. By then, even Americans of European descent had lost much of their taste for wine, the years of Prohibition having taken their toll.

The quality of American grown wines during the 1930s was also a major factor. It took about 30, 40 years, but American wines did begin to improve; and by 1983, following the first modern day “wine boom,” Americans were drinking 2.25 gallons per capita. Today it is up to just under 3 gallons — still less than what they drink in the U.K. and Germany (about 5.3 gallons), and considerably less than Italy (9 gallons) and France (10.1 gallons) despite these traditional wine producing countries’ recent drops in consumption (see Wine consumption in Europe, Jacub Marian).

Which is to say: The average American is still, comparatively speaking, just getting into wine. Hence, just beginning to grasp the nuances, such as the differences between wines meant to express varietal character and wines crafted to express the characteristics of specific places.

Generic Vs. Varietal Wines

California became a state in 1850, which (along with the attraction of gold) set off an explosion of newly minted Californians — many of them from European countries, and thus in need of wine. And so many of them planted grapes everywhere they could, from Napa and Sonoma all the way up into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, and from Mendocino all the way down to Los Angeles and San Diego.

Naturally, the earliest would-be winegrowers had no idea exactly which grape varieties would grow best in their newly adopted home, and so they typically planted several dozen different grapes in “one corner after another,” as Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in The Silverado Squatters (1883). Wine merchants who sold the wines made from those grapes had to identify their products in the only way Americans of European descent understood: by labeling them with European place names, which is exactly how most Europeans have always been (and still are) sold. So wines were given generic names like Burgundy, Chablis, Moselle, Sherry, Madeira, Port, and so forth. Because dozens of grapes were grown out in the fields, these wines were made from any and, often, all of those grapes — with absolutely no restrictions as to what grapes could go into any wine.

Never mind the fact that Burgundy in France is actually made from Pinot noir, and France’s Chablis is made exclusively from Chardonnay — things that are regulated by law in traditional European wine regions. It was a rare California Burgundy or Chablis that were actually made from Pinot noir or Chardonnay. In fact, since experimental plantings of Pinot noir and Chardonnay in California during the 1800s did not do nearly as well as grapes like Zinfandel or Colombard, virtually no California Burgundy or Chablis were made from the grapes originally associated with those place names. They were made from grapes like Zinfandel and Colombard. This was the way the California wine industry did business all the way up until the 1930s, and well after.

Post-Prohibition Reforms

A couple of years after Prohibition was repealed by the 21st Amendment (in 1933), the federal government finally got around to setting up a regulatory agency, called the Federal Alcohol Administration (FAA), to establish guidelines for the production and sales of wine and other alcoholic beverages in the interest of “preventing deception of the consumer.” At that time, the use of any grape to produce generic wines was allowed to continue, but there was a groundswell of opinion from more sophisticated quarters advocating for the production of wines made from specified grapes known to yield higher quality wines.

This led to the federal law defining what we now call “varietal wines,” which according to 1930s legislation required wines sold by the names of recognized grapes to contain at least “51% juice from that grape variety.” This legislation was supported by California’s Wine Institute, formed in 1934 to promote and market California wine, and also to advise the industry under the auspices of its Wine Advisory Board (the latter, established in 1938). The Wine Institute’s fundamental position was that the only way that the California wine industry would be able to expand would be to improve wine quality, and the production of wines made from higher quality grapes would eventually need to be the way to go.

U.C. Davis’ Department of Viticulture and Enology, originally established in 1880 with a mandate accorded by the state legislature to bolster the California wine industry, had closed down during the Prohibition years and was re-established in 1935. The school’s first post-Prohibition faculty member was Professor Maynard A. Amerine, who headed the department up until 1974. Very conscious of the high standards set by European wine regions, Amerine and his colleagues focused on supporting the California industry’s movement towards a concentration on fewer grapes of higher quality planted in the most suitable places, rather than the pre-Prohibition idea of planting anything and everything everywhere possible.

Ancient vine Mokelumne River-Lodi grown Carignan, a grape that U.C. Davis’ Maynard Amerine once described as “rarely distinctive,” yet was California’s most widely planted red wine grape between the 1940s and 1970s

In one of his 16 books penned over the years — called Wines, Their Sensory Evaluation (with Edward B. Roessler, 1976) — Amerine freely utilized the terms “varietal,” “varietal character” and ” varietal-labeled wine” as a way of distinguishing quality that could be perceived on a sensory level, while making no bones about what he thought were potentially the best grapes for California. For instance, white wines “capable of at least some recognizable varietal character,” according to Amerine, included “Chardonnay, Chenin blanc, Sauvignon blanc, White (Johannisberg) Riesling…” White wines that were “rarely capable of varietal character” included “French Colombard, Green Hungarian, Trebbiano…” Red wine grapes such as “Barbera, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay, Merlot, Petite Sirah, Pinot noir, Zinfandel” were cited as positively “recognizable.” Red wine grapes described by Amerine as “rarely distinctive” included “Carignane, Mataró [a.k.a., Mourvèdre], Mondeuse…”

The post-Prohibition push towards varietal wines as a way of making higher quality products more accessible to everyday consumers was also strongly advocated by a widely respected, New York-based travel writer and wine merchant named Frank Schoonmaker, who began encouraging California wineries to move away from generic labels and bottle wines as varietals as early as 1935. In his landmark book Frank Schoonmaker’s Encyclopedia of Wine (1964), Schoonmaker wrote: “A noble variety is one capable of giving outstanding wine under proper conditions, and better-than-average wine wherever planted, within reason… A noble wine is one that will be recognized as remarkable, even by a novice.”

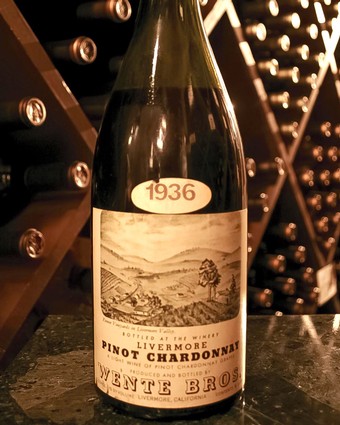

Bottle of the groundbreaking 1936 Wente Brothers Livermore “Pinot Chardonnay” (from the Wente Vineyards Library)

All the same, generic-labeled California wines dominated table wine sales in the U.S. all the way up until the end of the 1960s. Credit goes to the literal handful of brands that bottled varietal wines prior to the 1960s. Livermore Valley‘s Wente Brothers winery stands out as a pioneer, first bottling a Wente Brothers Pinot Chardonnay (the grape now correctly called, simply, Chardonnay) in 1936. In his 1948 book on California’s Best Wines, Balzer lauded Wente Brothers’ innovative marketing as a major step for California wine in terms of quality and prestige: “You can see how completely the Wente brothers believe in the idea, for all their wines are now marketed under proper varietal descriptions; Dry Semillon, Grey Riesling, Sylvaner, Sweet Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Blanc, and Pinot Chardonnay… the odious habit of comparison is eliminated once our wines are free of French names.”

1960s Push Towards Higher Varietal Percentages

In his 1976 book called Gorman on California Premium Wines, Robert Gorman cited Beaulieu Vineyard, Charles Krug Winery, Louis Martini Winery, Inglenook Vineyards, Wente Brothers, Stony Hill Vineyard, Buena Vista Winery, and Martin Ray as being among the top brands leading the California wine industry with premium varietal bottlings of significance. Writes Gorman, “By the early 1960s there was little tendency to parrot European place-names [among the aforementioned producers]. The trend was to let the wines appear under their own appellations — the place where were grown and the variety of grapes from which they were made…

“By the late 1960s, those winemakers who had laid an early foundation for premium wines were producing very high-quality wines… Both the success of these pioneers and the new interest in premium European wines had a profound effect. Within a decade, the California wine scene has virtually been turned upside-down.”

There was, however, a growing consensus at the time that the federal law allowing varietal labeling with a minimum of 51% of a stated grape going into wines was simply not enough. In his October 1969 article entitled “Is There Great Wine In California?” published in Esquire magazine, the noted (at the time) wine critic and bon vivant Roy Andries de Groot echoed the growing frustration with the old law among the growing legions of American wine aficionados:

Wherever I went [describing a recent tour of top California vineyards], I heard the fine producers describe the present law as “grossly misleading,” “dishonest,” “absolutely ridiculous.” They feel the law must be amended…

In every country, the first wines are those with strongly individual character of a particular type of grape. Bordeaux is dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon, Burgundy by Pinot noir. If you buy a French Chablis or Montrachet, the French government stands behind the label, to guarantee that the wine is made 100% from the Pinot Chardonnay grape. There is a specific legal definition of every wine village in France. This is known as the “controlled appellation” law.

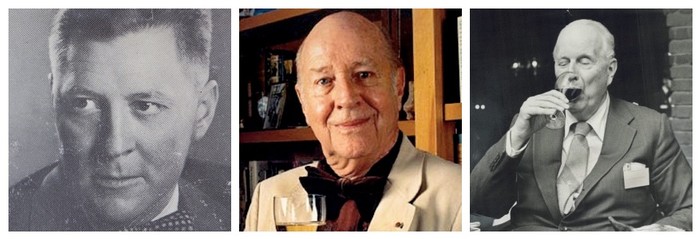

Three influential wine writers of the past who advocated for varietal labeling when the concept was considered a rare innovation (from left): Frank Schoonmaker, Robert Lawrence Balzer and Roy Andries de Groot

The U.S. has the weakest such law of any wine-producing country. If you buy a California bottle labeled “Pinot Chardonnay,” the law requires that only 51% of the wine in that bottle need to be from the Pinot Chardonnay grape. The remaining 49% can be cheaper juice from any lesser grape. The unfair competition against the fine producer is obvious. He makes his wine 100% from the noble and expensive grape and therefore has to charge, perhaps, $4 or $5 a bottle. His competition, taking full advantage of the 51% law, is still allowed to mark his label Pinot Chardonnay, but can sell his bottle for around $2.25. Yet one only has to taste the two wines side by side to realize the 100% single-grape is as a prince to the 51% pauper!”

Finally bowing to this growing sentiment, in 1978 the BATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, which took over regulation of alcoholic beverages in 1972) finally did pass an amendment raising the federal minimum for varietal wine labeling to 75%. This ruling went into effect on January 1, 1983.

Usage of the Term “Varietal”

A varietal wine is a type of wine named after the predominant grape in its composition. Federal guidelines require American wines to have a minimum of 75% of the grape identified on a varietal wine label, while some individual states have stricter standards. Oregon, for example, has a 90% requirement.

This term is correctly used when referring to the identity of a grape going into a commercial bottling but is often incorrectly used when referring to the botanical identities of grapes. For instance, when talking about Cabernet Sauvignon as a grape rather than a wine type, it is not called a “varietal.” It is called a “grape,” a “variety,” or a “cultivar.”

There are other sticklers for proper wine language who still say that “varietal” can only be an adjective, not a noun. The word, however, has long entered the domain of commonly accepted usage as either a descriptor or a wine type or category. It is perfectly okay, for example, to refer to Cabernet Sauvignon as “a varietal” as well as “a varietal wine.”

Where varietal terminology becomes tricky for American wine producers, however, is that only grapes formally recognized by the TTB (Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, which took over regulation of alcoholic beverages from the BATF in 2003) may appear on a label. The pioneering Lodi grower/producer Bokisch Vineyards, for instance, was not allowed to label their first vintage, 2001, of Graciano as “Graciano” because the grape was not listed by the ATF. After submitting evidence for Graciano’s long-established history in Spain, the Bokischs were able to get the grape listed and bottle their second vintage as Graciano.

The Primitivo vs. Zinfandel question is another example of TTB quirks. Primitivo is a clonal variant of Zinfandel, sharing the exact same DNA, and many growers prefer the attributes of Primitivo over that of other Zinfandel selections. The TTB recognizes Primitivo as a separate varietal category, and therefore many California wineries bottle a Primitivo separately from their Zinfandel. However, most growers sell their Primitivo grapes to wineries as Zinfandel — because that’s exactly what it is. Therefore, the vast majority of Primitivo grown in California is actually bottled as Zinfandel, regardless of TTB standards. This is not deception, it’s just logic.

Hux Vineyards’ Barbara Huecksteadt picking the rarely seen Marzemino grape in Lodi’s Mokelumne River AVA

Marzemino is still another example of a grape that, at this point in time at least, is still not recognized as a grape eligible for varietal labeling, even though it has been cultivated by Lodi’s Hux Vineyard since the late 1990s. Wineries have been getting around the rules by submitting their back labels as their front labels for TTB approval, identifying the wine simply as a “California Red Table Wine.” But because actual back labels are not as stringently regulated as front labels, you may prominently show the wording “Hux Vineyard Marzemino”—and this is what the consumer sees, reading the back label as the front label.

“Varietal Character” Vs. “Sense of Place”

The phrase “varietal character” has been used to describe sensory qualities associated with a particular grape identified on the label of bottling at least since the 1930s. The varietal character of a Cabernet Sauvignon, for instance, is usually that of a red wine that exudes aromas of blackcurrant, dark berries, some degree of herbaceousness, with a full body and generous tannin. The varietal expectation of a Zinfandel is that of a very berry-like red wine, medium to full in body/tannin and zesty in flavor.

The question today, however, is this: Is the correct or intense varietal character a mark of a superior wine? Moreover, exactly what is the varietal character of a Cabernet Sauvignon, a Zinfandel, a Chardonnay, or any other varietal-labeled wine?

One drawback of evaluating wine quality in terms of varietal character is that, as in all things, perception is everything. Wine critics, for one, tend to have different conceptions of what constitutes a varietal wine’s ideal qualities, and the perspectives of wine critics, in general, have grown increasingly different from that of, say, the sommelier trade, which tends to define quality by distinctions related to terroir, or “sense of place,” rather than varietal intensity.

A second drawback is that more and more consumers are also perceiving wine quality in terms of terroir regardless of how well a wine meets varietal expectations. Since the terroirs of, say, Rutherford in Napa Valley and the Adelaida District in Paso Robles are so different, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to evaluate their Cabernet Sauvignons in terms of the same varietal profile.

The same thing applies to Zinfandel grown in Sonoma’s Dry Creek Valley or Alexander Valley as opposed to Lodi‘s Mokelumne River. The movement away from expectations of varietal character has been an inevitable part of the evolution of the American consumer, trade, and media, as more and more commercial wines are appreciated for their representation of respective regions or vineyards rather than the fulfillment of varietal expectations.

Historically, Zinfandel in Lodi was never planted on shallow, rocky clay loam benchlands or slopes like in Sonoma County (top photo, Todd Brothers Vineyard, Alexander Valley); instead, all of Lodi’s Zinfandel went into deep, fine sandy loam soils on flat terrains (bottom, Soucie Vineyard). In terms of varietal character, the Zinfandels of these two regions couldn’t be any more different.

This way of looking at wine is long associated with the finest wines of Europe, which are largely labeled by place names rather than by the brand/varietal formula that began to typify the American wine industry, pretty much starting in the 1950s and 1970s. During that era, varietal wines were just beginning to supplant generic wines in popularity, and American wines were not nearly as distinctive or geographically diverse as they are today. Consequently, up until very recently, sensory characteristics associated with regions or vineyards have remained a huge blank, for trade and media as much as for consumers. Yet for Lodi, as with many other emerging American appellations, the key to establishing an identity has been to establish an appreciation of wines within the context of origins, as opposed to varietal qualities that could come from, really, anywhere.

There was, after all, a very good reason why American wines were originally marketed with generic labels, in reference to place names in traditional European wine regions: It is because in Europe the best wines are associated with places rather than grapes. It would be silly, for instance, to judge château-bottled grand crus vineyards from Bordeaux on the basis of their varietal definitions of Cabernet Sauvignon. Or Burgundy’s Chablis crus or Montrachet by how well they express the Chardonnay grape. Why should the best and most interesting wines of California, or from any other state, be perceived strictly in terms of varietal character? The finest wines of the world, after all, are defined by far more than their makeup of grapes.

As the finest American wines continue to proliferate in both quantity and prestige, our understanding and appreciation of our own wines are only bound to become more strongly associated with wine regions, vineyards, and even tiny blocks of individual vines within vineyards. A more complicated and perhaps elusive endeavor, to be sure, but a far more satisfying one to bonafide wine lovers!

Label for Lodi Native Zinfandel: an example of a varietal wine where varietal expression plays second fiddle to the vineyard source on both the label and in the sensory qualities of the wine itself

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine and crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.