JUNE 8, 2020. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

Competition for Soil Resources – Cover Crops vs. Grapevines

Competition between cover crops and grapevines is a phenomenon familiar to many vineyard managers. The dense, concentrated root systems of vigorous growing cover crops take up substantial amounts of soil moisture and mineral nutrients to support their growth (Figure 1). In so doing, such cover crops greatly reduce the supply of soil resources available to adjacent vines. The vine response is reduced growth vigor and canopy development.

Figure 1. Vigorous growing cover crops consume soil water and mineral nutrients, decreasing the quantities available to adjacent grapevines. (Progressive Viticulture©)

This competitive effect of cover crops can be a great benefit for overly vigorous vines. For low vigor vines, however, the effect is detrimental, resulting in severely restricted shoot growth. To sidestep such negative impacts, mow and disk cover crops very early in the growing season.

Competition for Soil Resources – Grapevine vs. Grapevine

Unlike those of cover crops, grapevine root systems are diffuse and extensive, with some roots reaching many feet. In most California vineyards, which are commonly situated on moderately deep to deep soils, only a small portion of the roots of adjacent vines intermingle due to the low density nature of their root systems. This is true even where vines are closely spaced in the row. For this reason, competition between adjacent vines for soil resources is seldom of sufficient magnitude to noticeably impact grapevine growth vigor.

Still, curtailing inter-vine competition through very wide vine spacing, as seen in some old head trained vineyards, increases the reservoir of soil water and mineral nutrients for each vine. This can be an important benefit for low-input, low production enterprises, such as dry farmed and organic vineyards.

In trellised vineyards, reduced competition is sometimes evident in the higher vigor of end vines, which have access to headland soil beyond the vine row and have additional sunlight exposure on the canopy end. Sometimes end vines lose their advantage where trees on the vineyard periphery encroach upon them above and below ground, thus seizing the competitive upper hand (Figure 2). Measures to limit such competition include careful tree canopy pruning and tree root pruning adjacent to the vineyard using a backhoe.

Figure 2. Trees on vineyard periphery shade grapevines, reducing their photosynthetic output. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Competition for internal Vine Resources – Too Much and Too Little

The preceding examples represent competition within a vineyard. Many times competition within vines is of greater practical importance. This is the competition between developing vine organs for internal resources, mainly carbohydrates and mineral nutrients. At the outset of the growing season, remobilized stored reserves from woody vine tissues are the initial resources for growth, but as shoots elongate and leaves expand, photosynthesis and root uptake increasingly contribute new resources.

The preceding examples represent competition within a vineyard. Many times competition within vines is of greater practical importance. This is the competition between developing vine organs for internal resources, mainly carbohydrates and mineral nutrients. At the outset of the growing season, remobilized stored reserves from woody vine tissues are the initial resources for growth, but as shoots elongate and leaves expand, photosynthesis and root uptake increasingly contribute new resources.

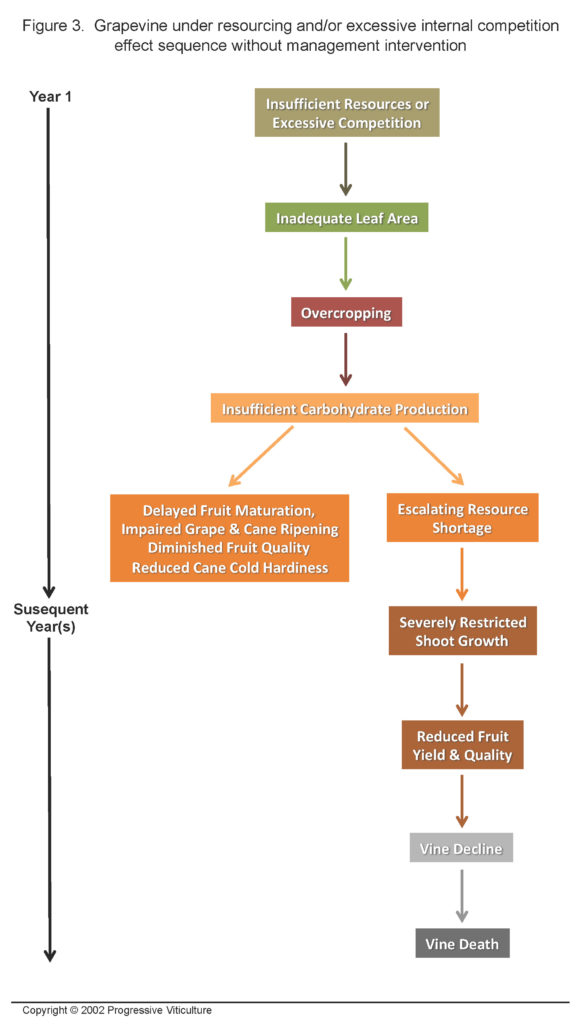

Early in the growing season, the growth vigor of all the shoots will be low when there are too many shoots and/or too few resources. In these instances, there is an urgent need to reduce competition through shoot thinning. Failure to do so will result in stunted shoots and too few leaves to produce the carbohydrates needed for fruit and cane ripening, and for storage in woody tissues for use next year. In other words, without management intervention, the vines are destined for overcropping and will possibly decline (Figure 3). If most shoots have at least two or three unfolded leaves, fertilization can provide additional resources to stimulate shoot growth.

The opposite condition, excessive growth vigor, occurs when there are too few competing shoots and/or too many resources. Under these conditions, shoot thinning intensifies growth vigor and compounds the problem, leading to an overabundance of foliage, fruit zone shading, poor shoot tissue integrity, and substandard fruit quality. Accordingly, avoid shoot thinning or at least, delay it as late as possible. Also, withhold irrigations to allow soil moisture depletion to a level that inhibits shoot growth. At the same time, restrict nitrogen fertilizer applications.

Sometimes, these measures alone are not enough to control excess growth vigor and additional remedial actions are required to create more internal competition. These include vine retraining to a form that supports more buds, less severe pruning, and as covered in the first section of this article, use of a competitive cover crop.

Competition for Internal Vine Resources – Using Apical Dominance to Advantage

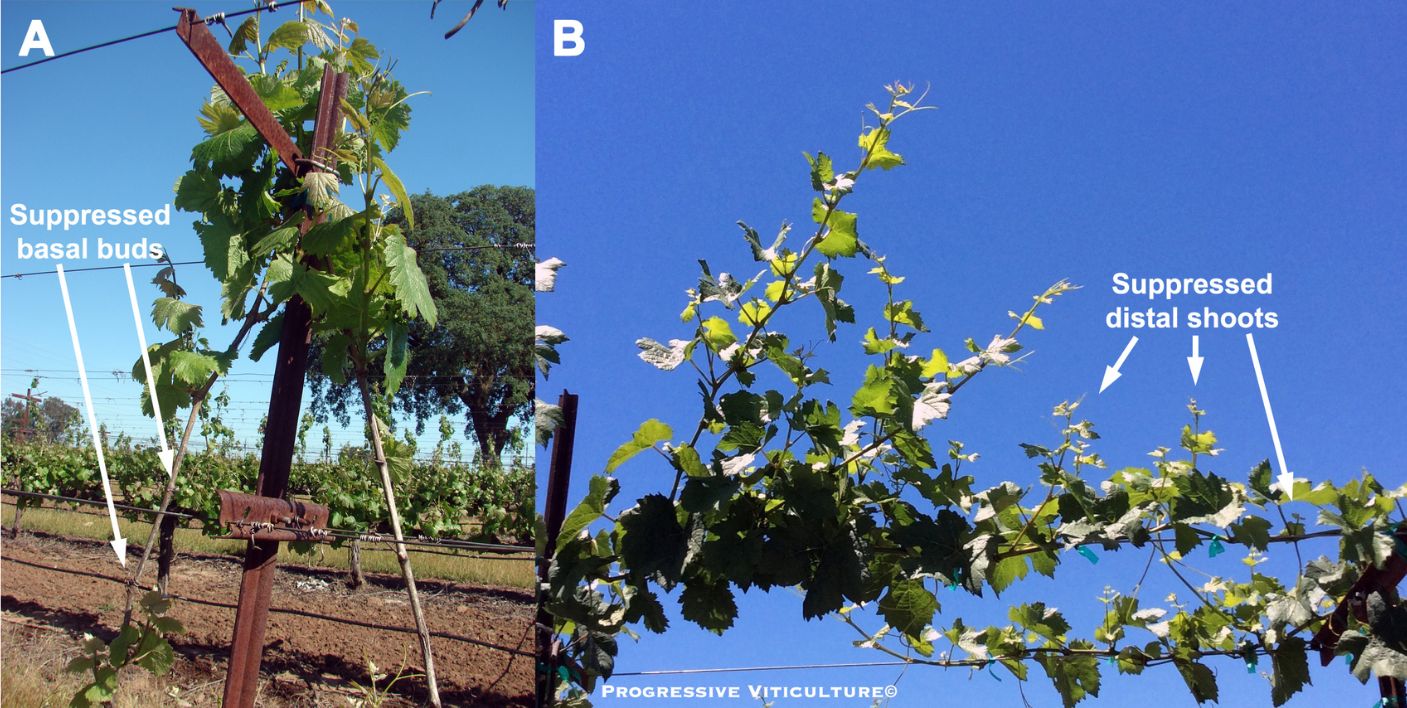

Before leaving the topic of competition between shoots there is one other important aspect to consider. The tips of vegetative organs, such as shoots, produce hormones. Hormones moving down the shoot from the tip suppress the growth of lateral shoots, which compete with the tip for vine resources. Apical dominance is the name for this suppressive phenomenon (Figure 4A). Apical dominance extends, although not as strongly, to adjacent shoots if their tips are in a lower position due to shorter shoot length or shoot draping (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Apical dominance effects: (A) early emerging, shoots on the apical end of a vertical cane suppress the emergence of basal buds and (B) early emerging, longer shoots on the proximal end of a new cordon suppress the growth of later emerging, shorter shoots at the distal end. (Progressive Viticulture©)

On established vines, apical dominance can be used to advantage while shoot thinning to lessen competition between shoots, improve canopy uniformity, and enhance fruit quality (Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop, May 02, 2017). Simply remove both the shortest and longest shoots, and retain shoots near the average length. This same principal applies to other vineyard practices that regulate vegetative organs, such as pruning.

Light tipping or hedging can also promote shoot growth uniformity on vines (Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop, June 06, 2017). Tipping of longer shoots temporary suspends their dominance. This creates a window of opportunity of several days for shorter shoots to grow without competition. The window closes as the apical lateral buds on longer shoots are released from dormancy and begin to emerge, but by that time there will be much less shoot length variation.

Competition for Internal Vine Resources – Fruit vs. Shoot

After the fruit sets and berries grow, clusters quickly become more effective competitors than shoot tips and lateral shoots. As a result, shoot growth slows appreciably or stops. This is desirable for vines with fully developed canopies, which can provide the necessary carbohydrates and direct them towards fruit maturation.

If, however, there are too few leaves (<14 to 16 per shoot), then either competition needs to be reduced or additional resources need to be applied to stimulate shoot growth and avoid overcropping (Figure 5). Reduce competition through cluster thinning. Simultaneously, apply the most effective resources for stimulating shoot growth to the soil, which are calcium nitrate (e.g. CN-9) with ample water.

In Summary

Manipulating competition within a vineyard and within grapevines is essential to directing and controlling growth, promoting complete canopy development, and optimizing grape quality.

This a modified version of an article published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services February, 2004 newsletter. The article was updated for this blog post on May 11, 2020.

Further Reading

Connor, DJ; Loomis, RS; Cassman, KG. Crop ecology: productivity and management in agricultural systems. 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press. 2011.

Garrett, HE. North American agroforestry: an integrated science and practice. Madison, WI, American Society of Agronomy. 209.

Kramer, PJ; Kozlowski, TT. Physiology of woody plants. Academic Press, San Diego. 1979.

Martin, G. C. Apical dominance. HortScince. 22, 824-833. 1987.

Salisbury, FB, Ross, CW. Plant physiology. Wadworth Publishing Company, Belmont, California. 1978.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.