MONDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2022. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Featured image: Overhead photo of Lodi wine festival in Lodi Lake Park, located along the Mokelumne River, the namesake of the appellation originally farmed by the region’s pioneers, starting in the late 1840s.

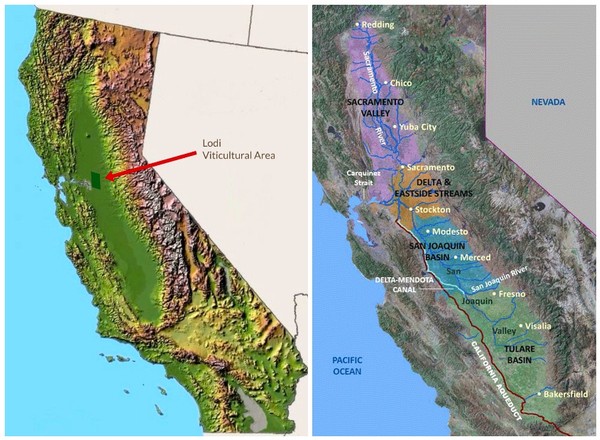

One of the reasons why the Lodi AVA (i.e., American Viticultural Area) still has a hard time being taken seriously by many of the wine cognoscenti is the region’s persistent association with the rest of the Central Valley. It is always amazing, in fact, when you meet Napa or Sonoma-based wine industry professionals who still believe that Lodi grapes are grown in a desert—presumably, just like the rest of the Central Valley.

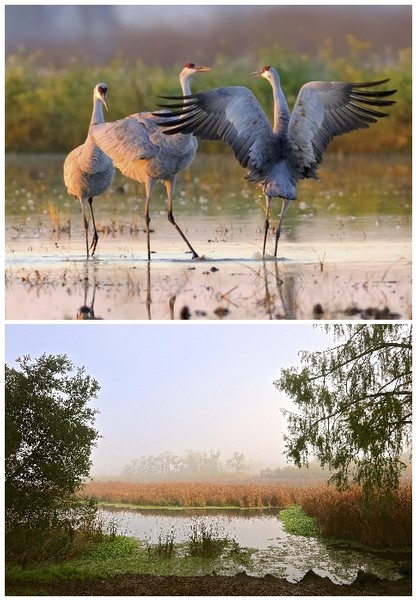

Yet there is nothing about Lodi that suggests a desert. If anything, everything about Lodi is about water. Lots and lots of water.

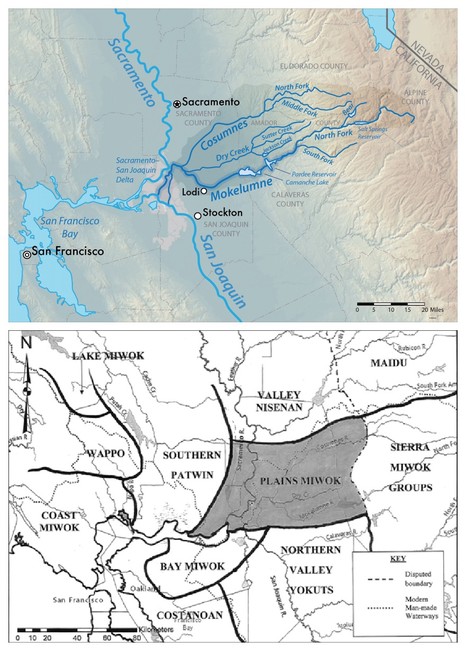

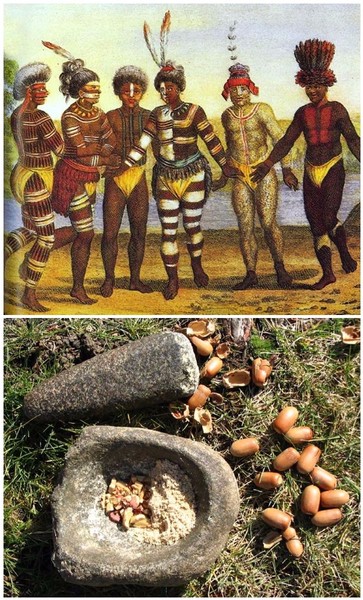

The Mokelumne River watershed was occupied for over 1,000 years by native Miwok tribes; particularly the Plains Miwok, who lived in the area now identified as the Lodi Viticultural Area.

Up until 1874, the City of Lodi itself was called Mokelumne (pronounced moh-KUL-um-nee), named after the river that dominates this watershed area and defines its topography. At that time it had been only 28 years since the first settlers of European descent had established their homesteads in this teeming river region.

For over 1,000 years, the indigenous Plains Miwok—who had fished in the multiple waterways of this area (in Miwok language, Mokelumne translates into “the place of the fish net”)—subsisted primarily on the acorns from the deep-rooted oak trees dominating the landscape.

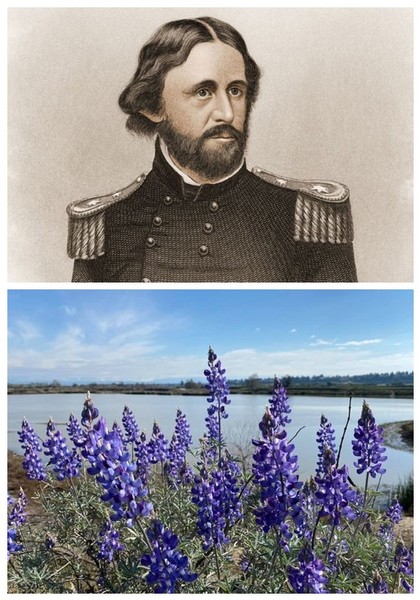

John C. Frémont and showy native Lupinus that he wrote about during his 1844 expedition taking him through the Mokelumne River area waterways.

First known as Rio Mokellemos, the present-day spelling of Mokelumne was first coined in 1848 by John C. Frémont. It was in 1844 when Frémont headed out from Sutter’s Fort (the site of present-day Sacramento) on a U.S. government-commissioned California expedition taking him southwards into San Joaquin Valley. We have Frémont’s own account of his first glimpse of the Mokelumne River region. Stopping at a site just west of present-day Lockeford, Frémont wrote in his journal:

March 25. — We traveled for 28 miles over the same delightful country as yesterday, and halted in a beautiful bottom oat the ford of the Rio de Los Mukelmnes, receiving its name from another Indian tribe living on the river. The bottoms of the stream are broad, rich, and extremely fertile; and the uplands are shaded with oak groves. A showy Lupinus of extraordinary beauty, growing four to five feet in height, and covered with spikes in bloom, adorned the banks of the river, and filled the air with a light and grateful perfume.

Marveling at the expanse of native grass peppered with golden poppies, vivid blue lupines, and gigantic oak trees, Frémont rhapsodized, almost poetically:

One might travel the whole world over, without finding a valley more fresh and verdant—more floral and sylvan—more alive with birds and animals—more bounteously watered—than we had left in the San Joaquin.

Five years before Frémont’s expedition, a visiting Easterner named Hall J. Kelley, known as “an apostle of westward expansion,” filed a report urging American annexation of California (which would be held by Mexico up until 1848). Kelley wrote of the Central Valley, south of Sutter’s Fort:

When I remember the exuberant fertility, the exhaustless natural wealth, the abundant streams and admirable harbors, and the advantageous shape and position of High California, I cannot but believe that at no very distant day a swarming multitude of human beings will again people the solitude and that the monuments of civilization will throng along those streams whose waters now murmur to the desert, and cover those fertile vales whose tumuli now commemorate the former existence of innumerable savage generations.

Nineteenth-century illustration of Plains Miwok, native to the Mokelumne River watershed, and ground acorn from indigenous oak trees that were part of their staple diet.

Kelley’s prediction of an imminent population explosion would come true, of course, within two short decades. The land was quickly settled by Americans or settlers arriving directly from Europe and other parts of the world, following the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 and spurred on further by the rush to statehood by anti-slavery proponents in Washington D.C.

Point being: Yes, Lodi is located smack dab in the middle of California’s Central Valley, which (contrary to errant assumptions) is not an AVA. Unlike most of the Central Valley, the verdant nature of Lodi’s topography is, in fact, the very reason why it is easily the largest winegrowing region in the United States. It is because of the naturally high vigor of its soils—arguably the richest (yet deep and well-drained, a factor ideal for grape growing) in the state—its moderate Mediterranean climate, and the all-important factor of direct access to water.

Sustainably farmed vineyards of the Heritage Oak Winery estate, tucked against the lush riparian growth of the Mokelumne River as it winds through the east side of Lodi’s Mokelumne River AVA.

Many of the mid-nineteenth-century fortune hunters arriving by way of San Francisco never made it to the mining camps of the Sierra Nevada foothills. Instead, they settled either on the coast or in the areas between the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and the foothills; particularly, as Christi Kennedy wrote in Lodi, A Vintage Valley Town, in “the rich land along the lush banks of the Mokelumne River.”

The first non-native family to settle in the area arrived just before the Gold Rush, in 1846. Kennedy writes that in 1849 Roswell Sargent, another one of the Mokelumne’s first settlers, “saw that the only sign of habitation by a white man was an abandoned log cabin apparently built by fur trappers,” and so they set down roots in this “wilderness land still dominated by oak trees, grizzly bears, and elk, just west of present-day Lodi.”

Wheat harvest during the late 1880s in Spenker Ranch, also planted to grapevines (foreground), in the heart of the west side of Lodi’s Mokelumne River appellation.

Once a settlement, informally named Mokelumne (officially changed to Lodi in 1874), was established near the river’s south banks, the first farm in the area consisted of 80 acres of wheat, followed quickly by more plantings of wheat as well as oats, barley, corn, potatoes, fruit and nut orchards, and land cleared for grazing livestock and horses.

If anything, the broader Central Valley is an ecological wonder in itself: an enormous, flat basin that was once an inland sea, carved out into the center of the state like a canoe from a tree. It is bounded by the California Coast Ranges to the west and the Sierra Nevada to the east, stretching 450 miles from the area around Redding in the north to Bakersfield in Kern County in the south.

California’s Central Valley, a flat basin that was once an inland sea, with its four distinctive watersheds (right), the Lodi AVA occupies the area immediately adjacent to the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta emptying into the San Francisco Bay.

Geologically, you could divide the entire valley into four major zones:

• The Lodi wine region lying immediately adjacent to the Delta, giving it a moderate Mediterranean climate

• The Sacramento Valley area to the north is located further from the coastal gap of the Delta, and marked by a hotter Mediterranean climate

• To the south, the dryer San Joaquin Basin and Tulare Basin regions, marked by climatic conditions categorized as desert.

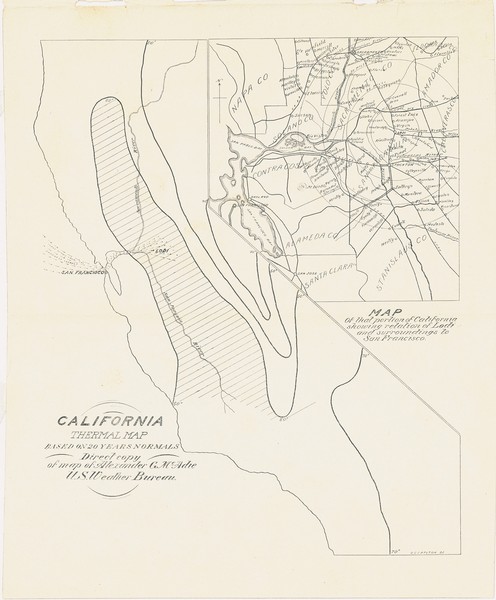

1904 U.S. Weather Bureau Thermal Map illustrating the influence of cool maritime air on the climate of the California Delta and the Lodi region immediately to the east.

Thanks to an abundance of water controlled by dams and irrigation systems, however, the entire Central Valley, from Redding to Bakersfield, produces an estimated one-quarter of all the food consumed in the United States (britannica.com).

Ever since the Lodi Winegrape Commission was formed by the region’s grape growers in 1991, one of the organization’s biggest challenges has been to refine the image of Lodi as being part of, but not equivalent to, the rest of California’s Central Valley. To describe the Lodi AVA as a typical “Central Valley” appellation would be like saying Napa Valley is a typical California coastal region.

Anyone, in fact, who has visited the coastal wine regions would tell you that there are more differences than similarities between Napa Valley and, say, Mendocino, most of Sonoma County, Santa Cruz Mountains, or the counties of San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara—entailing appellations stretching more than 500 miles apart. Not only do these regions not look the same, but they also produce completely different wines, even when made from the same grape varieties.

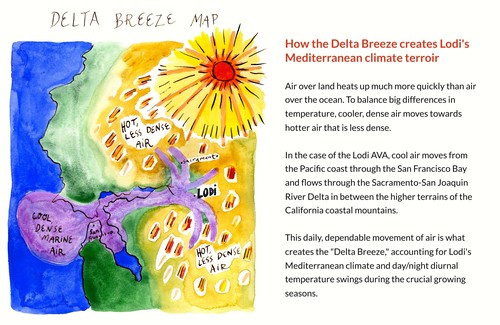

Climatically, the significance of the Lodi AVA’s location immediately east of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta can be summarized by one key factor: the Delta breezes, which blow through the appellation on a daily, dependable basis. The Delta waters drain into San Francisco Bay in an area shaped like an inverted triangle, occupying the only break in the entire California Coast Ranges. The elevation of most of the Delta area, in fact, is below sea level, the waters of the natural rivers and man-made canals kept at bay by a complex system of levees, first constructed between 1860 and 1880.

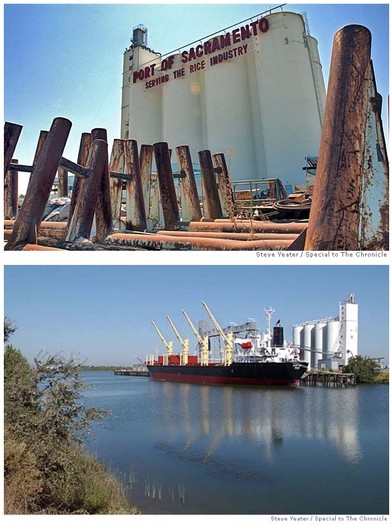

Despite being tamed by dams and levees, both the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River remain significant in width and depth. Consequently, both Sacramento to the north of Lodi, and Stockton to the south, were established in the mid-1800s as natural inland seaports, their deep-water channels accessible to ocean-going vessels. In 1854 Sacramento became the capitol of California because of its status as the state’s primary “River City” and proximity to its primary concentration of wealth—the gold mines of the Sierra Nevada foothills and the Central Valley’s quickly expanding farmlands

The farmlands centered around the Mokelumne area’s more modestly sized City of Lodi (population in 1878, about 450; today, approximately 68,000) have maintained their status as agricultural zones sandwiched between the bustling urban centers of Sacramento and Stockton. With its far western edge falling partially in the Delta’s rich, minus-zero-elevation terroir, it would not a stretch to think of the Lodi AVA as more of a coastal region than an inland region.

This accounts for the Lodi AVA’s climatic similarity to much of the California coastal regions—the winegrowing regions with temperatures and diurnal swings closest to Lodi’s are St. Helena in Napa Valley and Healdsburg in Sonoma County—in direct contrast with warmer climate agricultural regions to the south, stretching from Stockton to Bakersfield.

In fact, everything about Lodi—the marine air, easy access to water, the deep, rich river-influenced soils—points to this simple fact: It is Lodi’s natural resources that have made it a classic winegrowing region, larger than any other in California, and with more vineyard acreage than in all of the states of Washington and Oregon combined.

Historically, the most evident sign of the Mokelumne region’s potential for farming recognized by the nineteenth-century pioneers, according to Wanda Woock in her book Jessie’s Grove, was the enormous valley oaks indigenous to the terrain. Woock’s great-grandfather Joseph Spenker, a failed gold miner-turned-merchant, acquired his square-mile property in 1869. Writes Woock, “The land had hundreds of oak trees, and although it would work to clear some of them for planting, with the trees growing so abundantly he knew the quality of the soil would be excellent.”

Valley oaks (top) in Jessie’s Grove on the west side of the Mokelumne River-Lodi AVA; blue oaks (bottom), indigenous to the hillier areas of the Clements Hills AVA, on the eastern edge of the Lodi appellation.

Of the dozens of species of oak indigenous to California, the valley oak (Quercus lobata) is the largest. Valley oaks require a generous water table well within the reach of their roots, and soils sufficiently deep and rich enough to grow to their typical heights (up to 60 feet within 20 years) and reach their optimal longevity (up to 600 years).

The Mokelumne River watershed sits on an enormous aquifer which, in the 1800s, was readily accessible to farmers just a few feet below the surface. The soil that defines the Lodi sub-appellation of Mokelumne River is a rich alluvium consisting of sandy loam originating from pulverized granite (the base rock of the Sierra Nevada), layered over rivers over the past 15,000 years at depths of up to 100 feet before hitting clay hardpans. As such, a phenomenal terroir—great for oaks, and ideal for Vitis vinifera (i.e., the European family of wine grapes), another plant that thrives in deep rooting systems.

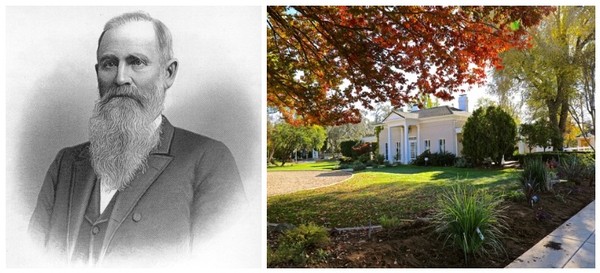

The Hon. Benjamin F. Langford and his original home in the Langford Colony, now part of the Paskett Winery estate.

During the 1850s the earliest settlers along the banks of the Mokelumne River began to diligently level the native oak trees, which had furnished over 60% of the diet of the native tribes who once lived there as hunter-gatherers.

One such settler was Benjamin E. Langford, who acquired his first Lodi area property in 1851 along the Mokelumne River in the vicinity of present-day Acampo, on the east side of present-day Lodi’s city limits. After milling all the native trees culled from his original 320-acre property, named “Langford Colony,” Langford planted wheat and established orchards of peach, apricot, plums, and almonds. Langford’s farmlands would balloon up to 3,000 acres, and he would go on to co-found the first Bank of Lodi while serving in the California State Senate between 1879 and 1900, becoming renowned as both “Father of the Senate” and “Honest Ben.” Today, Langford’s original home sits on the site of Lodi’s Paskett Winery.

Photo from around 1918 of schoolgirls frolicking in the Mokelumne River near Spenker Ranch on Lodi’s west side.

On the west side of the Mokelumne area, close to a tiny township that was named Woodbridge, Spenker first concentrated on wheat and barley, and then watermelons, but grew “excited,” according to Woock, about the possibility of growing grapes, “all the different varieties he could grow,” and “the fact they were to stay in the ground for many, many years to come” as opposed to being a crop that needed to be replanted each year.

To this day, a physical legacy to the region’s original settlers exists in the form of an undisturbed 32-acre parcel of valley oaks and native grass preserved by the Spenker family since 1869. The estate is now known as Jessie’s Grove, named after the daughter of Joseph Spenker, in tribute to her steadfast refusal to tear out this natural growth even during the Great Depression, when the family went through a period of severe debt.

It is, as such, a tribute to the Lodi appellation’s entire history, and to the natural verdant attributes of this unique winegrowing region.

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorials to The Tasting Panel magazine, crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media, and is the author of the new book “Lodi! A definitive Guide and History of America’s Largest Winegrowing Region.”

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.