MONDAY, AUGUST 18, 2025. BY MARC FUCHS (1) & STEPHANIE BOLTON (2).

(1) Plant Pathology, Cornell University, Geneva, NY

(2) Research and Education, Lodi Winegrape Commission, Lodi, CA

Featured image above: A cluster of vine mealybugs at various life stages in a favored petiole-cane junction site on a grapevine, being tended by an ant. Each mealybug pictured is capable of spreading leafroll disease from infected vines to healthy vines, within the same vineyard and beyond. Photo by Stephanie Bolton.

Leafroll disease and grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GLRaV3)

Leafroll is a devastating viral disease of grapevines that has profoundly changed viticultural practices in the Lodi district and beyond with the invasion of the vine mealybug. Leafroll was recognized for the first time in Germany during the second half of the 19th century (Martelli 2015, Martelli 2017) and later in California (Harmon and Snyder 1946). This disease reduces yield, delays fruit ripening, increases titratable acidity, lowers sugar content in fruit juices, modifies aromatic profiles of wines, and shortens the productive lifespan of vineyards (Bolton 2020). The economic cost of leafroll disease is estimated to be $90 million annually in California (Cheon et al. 2020).

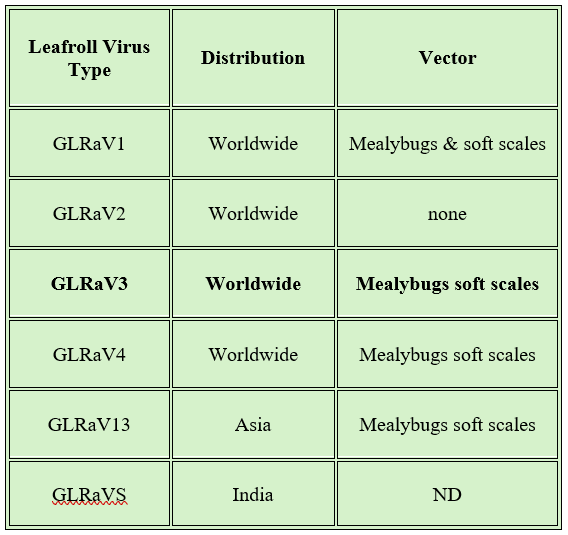

As of the writing of this article, six different viruses are involved in leafroll disease (Table 1) of which GLRaV3 is the most prevalent (Fust et al. 2025), including in the Lodi AVA.

Table 1. Viruses associated with leafroll disease, their geographic distribution and their vectors.

Abbreviations: GLRaV (grapevine leafroll-associated virus) and ND (not determined).

For GLRaV3 specifically, 12 different variants are currently recognized; these are named using roman numerals (I-XII). By analogy, there are 18 variants of SARS-CoV2, the causal agent of COVID disease, of which some are more transmissible among humans than others. Little information is available on how different GLRaV3 variants may uniquely contribute to spread in diseased vineyards.

Transmission of GLRaV3 by the vine mealybug

GLRaV3 is transmitted by several species of mealybugs and to a lower degree by soft scales (Table 1, above). Mealybugs are sap-sucking insects. At high densities, they can cause crop loss and rejection of fruit loads at wineries, although small infestations may not inflict significant direct damage (Bolton 2020, Daane et al. 2012). During feeding, mealybugs excrete honeydew (a sugary egestion) that often becomes covered with a black sooty mold, which additionally damages fruit clusters under high infestation levels.

Several mealybug species use grapevine as a host, but the vine mealybug, an invasive species, and the grape mealybug are the most abundant and widespread in California vineyards. The vine mealybug has 5-7 generations annually (Daane et al. 2012). The acquisition of GLRaV3 from infected vines and the inoculation of GLRaV3 to healthy vines are two critical steps for spread; each of these steps is occurring within only one hour of feeding by immature mealybugs (Almeida et al. 2013). Unassisted, vine mealybugs have limited mobility, but first instar immatures (crawlers) are likely dispersed over long distances by wind, field workers, ants, animals and vineyard equipment (Pietersen et al. 2017). Nonetheless, direct evidence on the dispersal of vine mealybugs in the vineyard is lacking.

Managing vine mealybugs and GLRaV3

Mealybugs are commonly managed via biological control, mating disruption, and application of insecticides (Bolton 2020, Chooi et al. 2024, Daane et al. 2021, Hogg et al. 2021, Pietersen et al. 2017). These responses are considered effective to manage the vine mealybug in relation to fruit marketability; however, limited success has been achieved so far for managing the vine mealybug as a vector of GLRaV3. In fact, experts state that once established in a vineyard or grape growing region, it is impossible to fully eradicate the vine mealybug (Daane, Unified Symposium presentation 2025).

Thus, managing GLRaV3 in diseased vineyards typically requires controlling mealybug populations, as described above, and roguing (removing infected vines) to limit virus incidence (Bolton 2020, Chooi et al. 2024, Pietersen et al. 2017). Roguing consists of scouting, mapping, and eliminating diseased vines which are then typically replaced with clean virus-tested vines. Symptomatic vines in red grape varieties can be most easily flagged around harvest-time, and it is recommended to validate the visual observation flagging process with commercial testing of both symptomatic and asymptomatic vines. Then, flagged vines are removed in the winter when the ground is wet to remove the highest number of roots for later replacement with clean, certified virus-tested vines (Bolton 2020). In white varieties and rootstocks, roguing usually occurs on a vineyard block basis rather than on a vine-by-vine basis because visual symptoms are non-existent or too faint to observe for these purposes.

Classic GLRaV3 (leafroll 3 virus) symptom of leaf reddening whilst the vein areas remain green in a red grape variety undergoing veraison. Remember that this symptom of leaf reddening does not occur in white grape varieties or in rootstocks, which poses a significant hurdle to our collective efforts to reduce leafroll disease statewide.

Classic GLRaV3 (leafroll 3 virus) symptom of leaf reddening whilst the vein areas remain green in a red grape variety undergoing veraison. Remember that this symptom of leaf reddening does not occur in white grape varieties or in rootstocks, which poses a significant hurdle to our collective efforts to reduce leafroll disease statewide.

Photo taken in Lodi in July 2025 by Stephanie Bolton.

Despite the establishment of clear management guidelines, vine mealybugs and GLRaV3 remain huge challenges for the grape and wine industries (Bolton 2023).

A new research project on vine mealybug dispersal and GLRaV3 spread

Lodi growers recently initiated a collaboration with researchers at Cornell University on the use of a unique method to mark and track vine mealybugs for the monitoring of their dispersal and for testing the potential influence of harvesters in assisting their dispersal. The collaboration between Lodi growers and Cornell University also centers on the development of a simple laboratory assay to distinguish GLRaV3 variants for increasing our understanding of leafroll epidemiology. More specifically, the objectives of this research project are to (i) identify GLRaV3 variants in leafroll diseased vineyards in the Lodi district to better understand spread dynamics, and (ii) monitor the dispersal of vine mealybugs on their own and through the potential influence of harvesters. This research is financially supported by the CDFA PD/GWSS Board. Stay tuned for progress updates in the future!

Further reading

Almeida, R.P.P., Daane, K.M., Bell, V.A., Blaisdell, G.K., Cooper, M.L., Herrbach, E. and Pietersen, G. 2013. Ecology and management of grapevine leafroll disease. Frontiers in Microbiology doi:10.3389/fmicb.2013.00094.

Bolton, S. 2023. Why it’s particularly difficult to protect your vineyard from mealybugs and viruses in California. Lodi Wine Growers Newsletter, https://lodigrowers.com/why-its-particularly-difficult-to-protect-your-vineyard-from-mealybugs-viruses-in-california/.

Bolton, S. 2020. What every winegrower should know: viruses. Lodi Winegrape Commission, pp. 138.

Cheon, J.Y., Fenton, M., Gjerdseth, E., Wang, Q., Gao, S., Krovetz, H., Lu, L., Shim, L., Williams, N., Lybbert, T.J. 2020. Heterogeneous benefits of virus screening for grapevines in California. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 71:231-241.

Chooi K.M., Bell, V.A., Blouion, A.G., Sandanayaka, M., Gough, R., Chhagan, A. and MacDiarmid, R.M. 2024. The New Zealand perspective of an ecosystem biology response to grapevine leafroll disease. Advances in Virus Research 118:213-272.

Daane, K.M., Cooper, M.L., Mercer, N.H., Hogg, B.N., Yokoya, G.Y., Haviland, D.R., Welter, S.C., Cave, F.E., Sial, A.A. and Boyd, E.A. 2021. Pheromone deployment strategies for mating disruption of a vineyard mealybug. Journal of Economic Entomology 114:2439-2451.

Daane, K.M., Almeida, R.P.P., Bell, V.A., Walker, J.T.S., Botton, M., Fallahzadeh, M., Mani, M., Miano, J.L., Sforza, R., Walton, V.M. and Zaviezo, T. 2012. Biology and management of mealybugs in vineyards. In: Arthropod Management in Vineyards: Pests, Approaches, and Future Directions, N.J. Bostanian, ed. Springer, pp. 271-307.

Fust, C., Lameront, P., Shabanian, M., Song, Y., Kubaa, R.A., Bester, R., Maree, H.J., Al Rwahnih, M. and Meng, B. 2025. Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3; a global threat to the grape and wine industries but a gold mine for scientific discovery. Journal of Experimental Botany 76:2985-3000.

Harmon F.N. and Snyder E. 1946. Investigations of the occurrence, transmission, spread, and effect of “white” fruit color in the Emperor grape. Proceedings of the American Society of Horticultural Science 47:190-194.

Hogg, B.N., Cooper, M.L. and Daane, K.M. 2021. Areawide mating disruption for vine mealybug in California vineyards. Crop Protection 148:105735.

Martelli, G.P. 2017. An overview on grapevine viruses, viroids and the diseases they cause. In: Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management. Meng B, Martelli GP, Golino DA, Fuchs M (eds), Springer Verlag, Cham, pp 31–46.

Martelli, G.P. 2015. Grapevine virology: A historical account with an eye to the studies of the last 60 years or so. Proc. 18th Congress of the International Council for the Study of Virus and Virus-like Diseases of the Grapevine, Ankara, Turkey, pp. 16-22.

Pietersen, G., Bell, V.A. and Krüger, K. 2017. Management of grapevine leafroll disease and associated vectors in vineyards. In: Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management. Meng, B., Martelli, G.P., Golino, D. Fuchs, M. (eds), Springer Verlag, Cham, pp. 531-560.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.